All in this together? The impact of tax and spending decisions by gender, disability, ethnicity and age

[Note: the views set out in this post are that of the author, not those of the Equality and Human Rights Commission]

[Note: the views set out in this post are that of the author, not those of the Equality and Human Rights Commission]

Who suffers – or benefits – when the government makes decisions on taxes, benefits and public spending at Budgets or Spending Reviews? While the Treasury has always published detailed information on the fiscal implications of various policy measures, the incidence – that is, which types of households or groups gain or lose – has generally been left to outside bodies like the Institute of Fiscal Studies. That changed as recently as 2010, when the Treasury began to publish analyses of the “distributional impact” of tax and spending decisions; that is, how changes affected households at different income levels.

But it’s not just about income levels. Inevitably, tax and spending decisions affect different groups differently: women and men, disabled people and others, and so on. And, as a result of the Equality Act 2010, public bodies – including the Treasury and other government departments – are legally obliged to consider the potential effects of their decisions on equality of opportunity. For many decisions taken by government departments, that means preparing an Equality Impact Assessment or its equivalent; but how do you do an EIA for a Budget or a Spending Review? Since 2011, NIESR has been working with the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) to work out what this means in practice. Today the EHRC published a new report, based in part on our research, setting out the progress made so far and making some further recommendations.

The report identifies some significant improvements. In particular, the Treasury has introduced a much more systematic approach to collecting data from government departments about the potential impacts of decisions on different groups. It also makes a number of recommendations for further improvements, around accountability, data, and analysis. In this blog, I’d just highlight a couple of points – which are my views, not necessarily those of the EHRC.

First, the current position represents a substantial amount of progress relative to the situation of 20 years ago, when even “women’s issues” were regarded as a marginal concern, or 5 years ago, when both analysis and policy consideration were at best ad hoc. The volume and quality of analysis inside government has clearly improved, and there is some degree of systematisation, particularly for individual measures. And context is very important – as everyone who’s ever worked in the Treasury knows, the nature of Budgets or Spending Reviews is that multiple decisions on policy measures are taken in a very short space of time: pressure on Treasury officials (and Ministers and Special Advisors) is intense. It is unrealistic to expect them to undertake a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the potential equality impacts of every single measure.

However, there’s still work to be done. Not unreasonably, worrying about equality often comes second to doing the actual work of getting a policy measure written up, costed and approved, particularly when data is scarce or difficult to interpret. But that often means that in practice the default option is to assume there’s no significant differential impact at all, even when common sense tells us that’s not the case. And, again not unreasonably, the temptation is to highlight “positive” impacts – good stories – while paying less attention to negative ones. For example, in the Equality Impact Assessment published alongside Spending Review 2013, the Treasury noted (correctly) that “the introduction of tax-free childcare, announced in Budget 2013 is expected to help parents, particularly women, return to work after parental leave.” However, there was no mention of the implications of various welfare measures designed to save £350 million a year, for example extending the waiting period for JSA from 3 to 7 days and increasing work requirements for lone parents with young children, even though some of these will clearly have a differential impact on women and men.

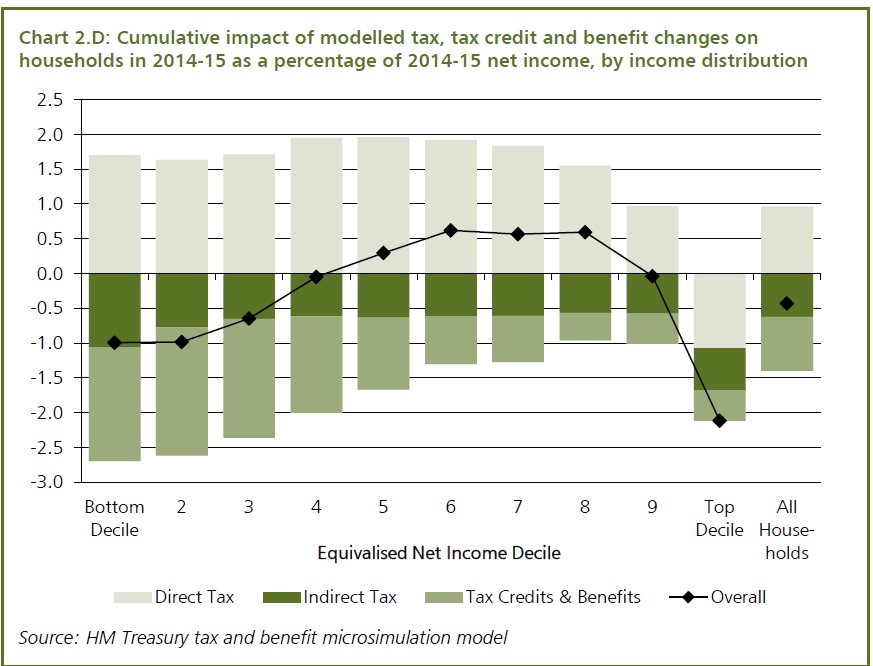

But perhaps the most important issue highlighted in this report, as in previous ones, is the need to look at the cumulative impact of all the decisions taken at any one time, as in a Budget or a Spending Review. The Treasury does this already for income, as shown in this chart; but it does not do so for gender, age, ethnicity or disability. In my view, there is no reason, either in theory or in practice, why such analyses should not be carried out – and published.

If the Treasury did produce charts like this by gender, disability and so on, are they likely to show that policy decisions bear more heavily on some groups than others? Almost certainly. It’s almost inevitable, for example, that very significant cuts to working age welfare benefits will hit disabled people considerably harder than non-disabled people, because a very large proportion of that budget is spent on disabled people.

So the “disproportionate impact” is not because the government has deliberately chosen to discriminate against disabled people – it’s because the government has chosen to cut the working age welfare budget. Nevertheless, it is a choice, the impacts are real, and the analysis is feasible. It seems to me very hard to argue that producing and publishing such analyses, so as to better inform public debate about the impacts of policy and policy change, isn’t exactly what both the spirit and letter of the Equality Act 2010 are about.

So for these reasons, the EHRC recommends that the Treasury “develop a methodology for modelling the cumulative impact on different groups for use in future spending reviews and financial policy decisions.” And to show that doing this is both feasible and useful, the EHRC has commissioned NIESR, working with Howard Reed of Landman Economics, to develop and pilot such a methodology. The results will be published later this year – so watch this space.