Brexit, migration and the labour market

What do today’s labour market statistics tell us about what’s going to happen to the UK labour market as a result of the referendum result? On the face of it, not much. The headline figures for employment, unemployment and so on are based on Labour Force Survey data for the months for April to June (and the changes are calculated with respect to the three months prior to that). The “single month” statistics do show a small uptick in unemployment (from its April low of 4.8% to 5.1%) – but these numbers are volatile, which is why the ONS doesn’t use them as the headline.

What do today’s labour market statistics tell us about what’s going to happen to the UK labour market as a result of the referendum result? On the face of it, not much. The headline figures for employment, unemployment and so on are based on Labour Force Survey data for the months for April to June (and the changes are calculated with respect to the three months prior to that). The “single month” statistics do show a small uptick in unemployment (from its April low of 4.8% to 5.1%) – but these numbers are volatile, which is why the ONS doesn’t use them as the headline.

However, there is actually some post-referendum data in the release, on Jobseekers’ Allowance claims. After several months in which JSA claims have been relatively flat, in July they actually fell. Perhaps even more interesting are the figures for “inflows” and “outflows”. As my former DWP colleague Bill Wells has noted, UK recessions seem to manifest themselves more in job separations than in new hires (that is, any rise in unemployment comes, arithmetically, mostly from more people being fired rather than fewer people being hired). In fact the number of new claims for JSA fell to a historic low in July. While this reflects in part the long-delayed roll-out of Universal Credit, it is hard to see anything in this data to suggest that the labour market slowed much in July.

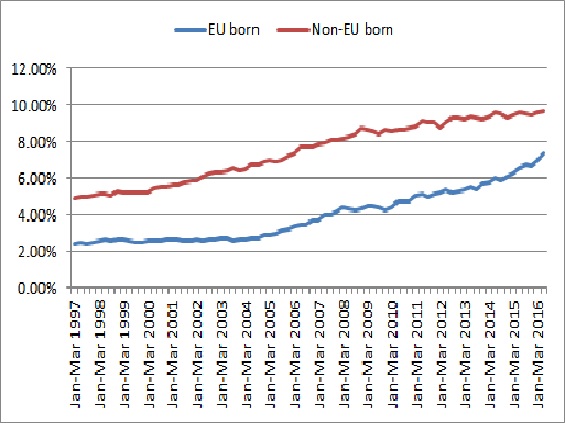

And what about migration? Again, there is no post-referendum data in today’s release (and nor will there be in the Quarterly Migration Statistics released next Thursday). However, today’s data shows that in the last quarter, essentially all the increase in employment was accounted for by foreign born workers; the number of UK-born workers was flat. Non-UK born workers now make up just over 17% – more than 1 in 6 – of those in work.

Over the past year (since these statistics are not seasonally adjusted, it’s better to look at the annual change) the total increase in employment has been just over 610,000; of this, the UK born account for about 250,000, EU (non-UK) born for 280,000 and non-EU born for 80,000. For the umpteenth time, this does not, repeat not, mean that more than half of all “new jobs” went to foreign-born workers. As the ONS say:

These estimates show the number of people in work and changes in the series show net changes in the number of people in work (the number of people entering employment minus the number of people leaving employment). The number of people entering or leaving employment are larger than the net changes. The estimates therefore do not relate to “new jobs” and cannot be used to estimate the proportion of new jobs that have been filled by UK and non-UK workers.

Still, one thing today’s figures may give us is the “high water mark” for the impact of EU migration on the UK labour market. I have always been very reluctant to make forecasts about migration flows – it is exceptionally difficult for a number of obvious practical and methodological reasons. Also, of course, such forecasts tend to be misrepresented, deliberately or otherwise, as the famous “13,000 EU migrants” case shows. Nevertheless, I am prepared to say that I would expect to see a sharp fall in net migration from the EU over the next year, for several reasons:

- Even before the referendum, employment growth in the UK had slowed (whether as a result of Brexit-related uncertainty, or, perhaps more likely, of other factors).Meanwhile Unemployment is falling both in the EU as a whole, and in the Eurozone.Moreover, for some countries at least (in particular Romania and Bulgaria), the very high levels of recent inflows is likely to reflect the impact of the lifting of transitional controls in 2014; this seems likely to run its course. So even if there had been no referendum, I would have expected immigration to fall back somewhat from its peak earlier this year.

- The referendum could make this fall much sharper. This is not just because of the overall economic impact of Brexit on growth, output and employment, about which we still have little hard data, although there is a strong consensus that the economy is already slowing significantly.A Brexit-related slowdown is likely to impact some sectors/regions – such as the finance sector in London – that employ large numbers of EU migrants. Moreover, migration from some EU countries – Poland for example – appears to respond quite quickly and substantially to exchange rate changes, presumably because migrants compare the salaries that they could earn at home to what they can earn here (and, in part, remit back to family).The value of the UK minimum wage, expressed in zlotys, has fallen by almost 15 percent already.

- To these economic reasons must be added legal and psychological ones.EU citizens already resident here may have a legitimate expectation, supported by most if not all politicians, that they will be allowed to remain legally indefinitely. But there will inevitably be a prolonged period of uncertainty before we know exactly what that means. If people cannot plan with any confidence, not just about themselves but their families, they are less likely to come and less likely to stay . Moreover, not only have we seen isolated but very unpleasant outbreaks of racism, with calls for EU citizens resident here to leave, but there is a much more widespread and more general sense that they are no longer welcome. There is already some anecdotal evidence that this is leading to some to contemplate returning to their countries of origin.

What will this mean in terms of numbers? This will depend crucially on economic and labour market developments over the next few months. But I’d be surprised if net migration from the EU were running even at half its current level in a year – and it could be much less. It would, of course, be hugely ironic if it was the referendum result – rather than any change in policy – that led to the government hitting its “tens of thousands” target. Equally ironic, but much more serious, will be the economic consequences. The fiscal impact of a large fall in EU migration for work purposes will make the post-referendum hole in the public finances even bigger.