The 2022 Survey of Economists

What can we expect in 2022? For the first Monday Interview of the year, we outline some of the policy tensions that currently exist and some of the systemic challenges within the UK economy that need to be faced.

At the start of every year, economists tend to be asked by the media or, indeed, key decision-makers what they think is going to happen over the next year. For example, last week the FT published the results of its annual survey. But let me be clear: we do not know! The only thing we do know is that we will be wrong and we will have to learn from our mistakes. What we can though say is something about the constraints that we have identified and the policy questions that need to be addressed should alternate paths emerge. Our Outlooks published next month will further address various scenarios that in aggregate describe the risk to a central case view about the economy. Since 2014, the Centre for Macroeconomics has published a regular survey of academic economists’ views on a range of questions and it is worth not only looking at the aggregate but also the individual responses for some idea of colour and complexity.

As we look into 2022, there is a clear tension at play. There is a strong urge in many, which I share that after nearly two years of living under the cloud of Covid-19 we need to move on as society and learn to manage the risks it poses without the ever present threat of lockdowns and shutdowns, which we can deal with as an extraordinary event but not as the norm. On the other hand, the Covid-19 pandemic is not yet over with a new variant raising concerns as to whether it is safe to come out from under the cloud and delaying the return of normality. Nobody wants to be the last solider killed just before an Armistice. We may need to think a little harder about support we can offer to sectors and regions that may be particularly vulnerable to the impact of Covid-19. The longer-term issues raised by Covid-19 remain and need to be addressed, specifically the state of health care (here and abroad), the quality of jobs, the need for regional regeneration (aka levelling up) and the question of how we ensure robust levels of economic progress. Covid-19 poses the same questions as we have always faced and ought to provide some convincing evidence for this generation and several to come that a change has to come.

Will the UK economy outpace or lag behind other developed economies in 2022 and why?

The UK economy does not look well placed to lead the advanced country pack in 2022. A combination of a ragged edge over Brexit and political uncertainty will continue to hamper what might otherwise have been a stronger recovery. Specifically, trade, investment and FDI will are unlikely to recover strongly and the skills gap in the labour market simply cannot easily be addressed very easily in the coming year alone.

To what extent will the Bank of England be in control of inflation by the end of 2022?

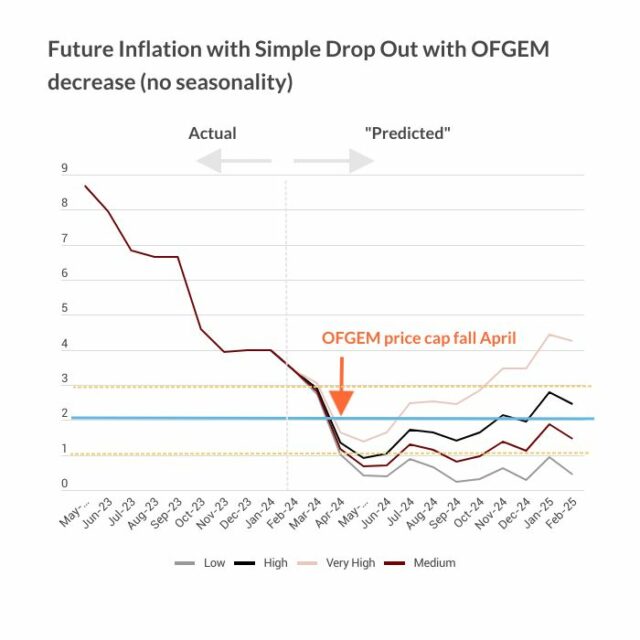

An operationally independent central bank with a floating exchange rate chooses the inflation rate it wants in the medium term. And inflation does seem likely to fall over the course of 2022 but more so if the Bank could be clearer about its reaction function and the preparedness to raise interest rates from extraordinarily low historical levels. The ground for quantitative tightening must be prepared and some mapping out of how we will return to normal interest rate levels.

To what extent will the UK look like a high wage, high productivity economy at the end of 2022 — and will people feel better or worse off than they do now?

The end of 2022 is far too short a horizon to shift the bad equilibrium of a low wage-high employment-low productivity economy into the one we all want. We have ended up in a world of low levels of capital per worker as part of a 30-year process of relatively low levels of investment. This leaves the economy vulnerable to shocks and will mean that the median family is unlikely to feel much better off materially by the end of 2022. But if the Covid crisis is behind us and there is full employment that may be an acceptable outcome relative to many other alternatives.

Is there anything else you would like to tell us?

Fiscal policy continues to confuse an instrument — the deficit — with the objective — supporting economic wellbeing. We do need to cast a more stern look at the Chancellor’s budgetary plans in the medium term and the extent to which they will support a levelling up plan that is in danger of not surviving first contact with the regions.