Are Football Fans Irrational?

Football is a truly global sport. Behavioural economics can now be used to chart this phenomenon and its knock-on consequences. The vagaries of our team’s fortunes affect us much more than we think and can have many unfortunate consequences. It is well known that football outcomes can affect absenteeism at work, drunkenness, and civil disorder. Indeed research in the US has also linked NFL results to domestic violence.

Football is a truly global sport. Behavioural economics can now be used to chart this phenomenon and its knock-on consequences. The vagaries of our team’s fortunes affect us much more than we think and can have many unfortunate consequences. It is well known that football outcomes can affect absenteeism at work, drunkenness, and civil disorder. Indeed research in the US has also linked NFL results to domestic violence.

In a recent paper we showed that the pain felt by football fans after a defeat is more than double the joy of winning. Moreover, the pain lasts twice as long after a loss than joy does after a win and if you are actually at the match the pain is double again. The pain is also worse when your team loses to opponents who are rated lower than your team.

We analysed two million responses from 32,000 people on a smartphone app called Mappiness, which randomly ‘pings’ them and asks users how they are feeling, what they are doing, where they are and who they are with. Screenshots of the some of the app’s screens are shown below.

A respondent’s happiness is calibrated from 0-100 and all our analysis is measured relative to an individual’s own normal state. To put the numbers into context: Intimacy or sex with a partner gives you +12, listening to music +3; being sick in bed -19; and working or queuing -3. We found effects of football which are comparable to the biggest of these numbers.

By combining this rich data with GPS locations of football stadia and times and results of football matches over three years, we were able to pinpoint football fans and monitor their mood in the build up to and aftermath of matches. Even though in-match mood levels were not analysed, we find that the cumulative effect of being a football fan is negative on average. This begs the question of whether it is sensible to be a football fan and follow a team.

By quizzing people in the moment via a random ping on their phone, the app reveals a much more accurate snapshot of momentary happiness than traditional research techniques, using retrospective memories, in which responses can be filtered through rose-tinted glasses.

On average, fans were 3.9 percentage points happier in the hour following a win, dropping off to 1.3 and 1.1 points in the second and third hours. A defeat, meanwhile, caused a drop in happiness of 7.8 points in the first hour, and 3.1 and 3.2 points in the second and third hour. This basic pattern can be seen in the graph below where the green line shows the happiness above your normal state after the game has ended hour on hour. (The bars show the 95% confidence interval on our estimates.) The red line shows the same larger negative effect for your team losing. The orange line is the effect of your team drawing – which is mildly negative but the effect dissipates after an hour. Interestingly the blue line shows what all fans experience prior to the game – a small 1.5 point high – possibly in the pub beforehand having a drink with your friends or family, imbued with optimistic expectations.

The joy and pain is felt even more keenly by those fans actually in the stadium. The jubilation of a win felt by those attending a match is over double that for those watching at home, boosting happiness by around 10 points. Remembering the context, only lovemaking or intimacy with a partner had a bigger effect on happiness across all the millions of responses to the Mappiness app. The flipside is that the sting of defeat becomes even more extreme, with a dramatic drop of 14 happiness points if you are in the stadium to see your team lose. Again, only being ill in bed has a worse effect on you.

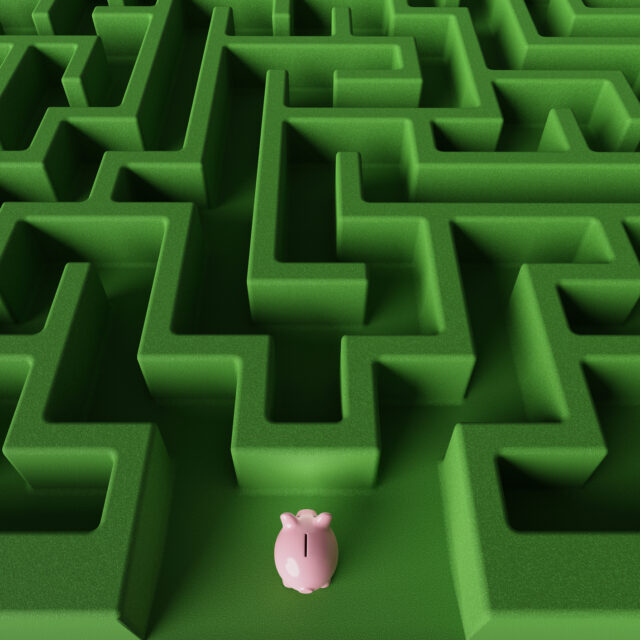

So the substantive question for our research remains – is following a football team an irrational thing to do? On the face of it – the answer is a qualified ‘yes’ as the impact of its immediate results is going to be – on average – worse the than the joy. So why do fans follow their teams? Some answers you get are: it’s part of who I am; it’s the camaraderie of belonging to a tribe, being bound up with lifetime allegiances with family and friends; the anticipation and expectation of the pleasure despite the pain; the massive highs of the goals going in and the good days are worth all the pain.

Perhaps also the answer lies partly in the pleasure of simply anticipating the spectacle of a live football match. We enjoy the unfolding drama and are naturally curious to see ‘how the story ends’.

It is also possible that fans systematically over-estimate the probability of their team winning and never revise or learn from experience. Another explanation the data suggest is that being a football fan is addictive, with fans always trying to get back the massive high of seeing your team win in person. In which case rational expectation may play no role in team allegiance.

Football is intrinsically part of who we are and our identity. Fans associate themselves with their team in a visceral bond. On Saturday 21st April Sunderland lost to Burton to be relegated to the third tier of English football for the first time in 30 years. A Sunderland fan responding to a debate about whether their players should be clapped off the field last Saturday if they lost, said: “If it happens, I’m not going to clap like. That’ll show them I’m properly vexed.” As a supporter he is part of the team – he sees them and so he believes they see him.

Another Sunderland fan likened the treatment that his team has meted out to him personally as feeling like a punch bag. He clearly feels those blows mentally and physically.

Football allegiances are lifetime brands on our souls. A young Sunderland fan – Ben, aged 9, from Witherwack near Sunderland being interviewed on BBC Radio Newcastle after the relegation game this Saturday was able to expand on the weaknesses of his team in great detail. Asked at the end of the interview if he would be going to watch Sunderland next season in League One (the third tier of English football) his response was: “Of course, you never know, they might even win some games”.