Can we solve the UK’s productivity puzzle?

In the years since the financial crisis in 2008, the UK has seen poor GDP growth combine with sustained employment levels to push down output per worker. In this blog, Alex Bryson and John Forth explain what we know about why labour productivity has so been so dismal and whether we can solve the ‘productivity puzzle’.

In the years since the financial crisis in 2008, the UK has seen poor GDP growth combine with sustained employment levels to push down output per worker. In this blog, Alex Bryson and John Forth explain what we know about why labour productivity has so been so dismal and whether we can solve the ‘productivity puzzle’.

In the spring of 2008, the world was hit by the biggest recessionary shock in living memory. The shock – subsequently labelled the Great Recession – was felt across most developed economies in the world and many in the developing world. Its origins lay in a global banking crisis linked to exposures to bad mortgage debts in the United States. In Europe, the era of sustained economic growth enjoyed for nearly two decades was reversed overnight. Investor uncertainty triggered stock market crashes throughout the world, firms suffered from sudden credit tightening and demand for goods and services dived. In the UK, the crisis was notable relative to previous recessions for three things: the enormity of the output shock; the muted unemployment response; and the very slow rate of recovery.

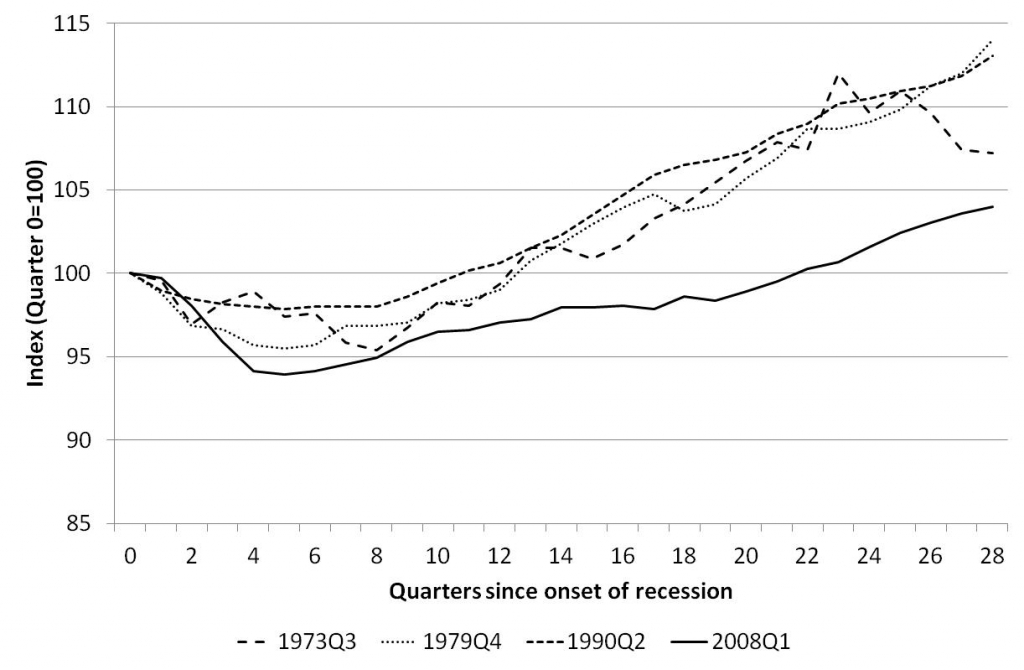

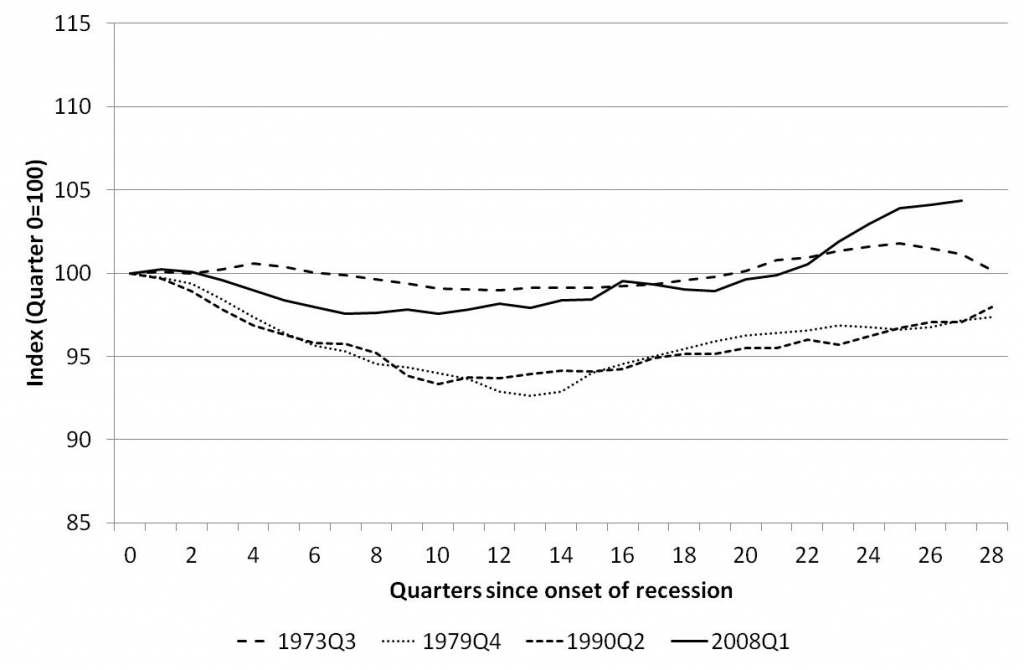

The initial drop in GDP of 5 per cent was steeper than in previous recessions and the UK economy has performed particularly poorly in the years since. In 2014, output per hour remained 0.4 percentage points below the level seen in the pre-recession year of 2007 (Figure 1). Yet at the same time, although employment levels fell – as you’d expect with a sudden fall in demand for goods and services – they didn’t fall by anything like what we might have expected from previous recessions and the fall was considerably smaller than the decline in GDP (Figure 2). Furthermore, employment recovered more quickly, exceeding its pre-recession level in 2012 Q3 (a full year before the recovery in output).

Figure 1: Depth of the Output Shock and Slow Rate of Recovery

Figure 2: Employment Levels in Recent Recessions

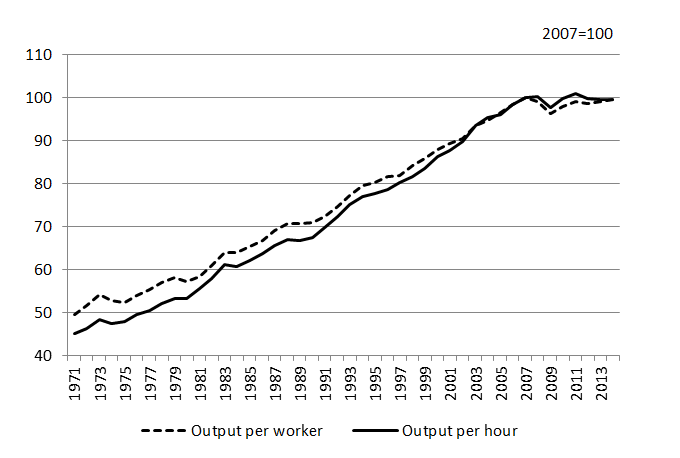

Poor GDP growth and sustained employment levels thus combined to push down output per worker. The fall in output per hour was not as substantial in the period immediately after the recession, since a growth in part-time working meant that hours per worker fell more steeply than employment; but there has been no overall progress on either measure since 2007. In this sense, the UK stands in contrast with the United States where output per worker and output per hour have both risen steadily over the past six or seven years and now stand around seven percentage points above the level seen at the end of 2007 (for data, see Office for National Statistics). This means that labour productivity in the UK was 15-16 percentage points below the counterfactual level had productivity grown at its average rate before the recession; this compares with a productivity gap of around six percentage points for the rest of the G7.

Figure 3 Labour Productivity Growth in the UK, 1971-2014

Simply pointing to the trends in the numerator and denominator is only a starting point in seeking to understand what has become known as the UK’s ‘productivity puzzle’. There are really two puzzles. First, why has economic growth taken quite so long to recover in the UK? And second, why has the labour market responded so differently to recession this time compared with earlier recessions? In neoclassical economic analysis, firms respond to demand shocks by laying off workers, thus maintaining labour productivity. Yet this didn’t happen – at least, not to the same extent as in previous recessions. A second and related puzzle is why economic growth has taken so long to return post-recession, as indicated by a slow return to the pre-recessionary peak in GDP: what has been going on and what can be done about it?

Let’s start with Salient Fact Number One. As Rebecca Riley and others have pointed out, output per worker declined across the economy, in most sectors and in most firms. In contrast to Germany where it was confined to the export sector, the UK recession was felt by the vast majority of firms and workers, although of course some were hit more heavily than others. We can therefore discount stories that are sector-specific.

Salient Fact Number Two is that any cleansing effect due to the recession killing the least productive firms was very muted indeed: the long tail of poorly productive firms remained in place. These firms, sometimes labelled ‘zombie’ firms because they kept going despite looking dead to all intents and purposes, have dragged down overall productivity.

Salient Fact Number Three is that the unprecedented fall in output was accompanied by a large decline in real wages not seen since the nineteenth century, a decline that is all the more surprising in the light of historically low inflation rates. Although economists have yet to identify the mechanisms that led to this real wage decline, some point to the declining bargaining power of trade unions and employees in general. Whatever the cause, this real wage decline may have encouraged employers to retain labour at a time when, if their price relative to capital had been higher, workers would have been laid off. Many employers were therefore able to pay those wages and were minded to do so, rather than lay workers off, partly because many came into the recession after a period of good profits – unlike in the recession of the early 1990s – and because some wished to avoid the heavy costs involved in firing high-skilled labour only to have to re-employ it in the inevitable upturn.

Declining labour costs means that firms may have been tempted to substitute labour for capital, resulting in capital shallowing – a process that would ordinarily result in declining labour productivity. In fact, although there is some disagreement due to difficulties in estimating capital stocks and flows, this appears not to have happened to any great extent. Instead, what has emerged is Salient Fact Number Four: firms experienced a decline in total factor productivity (TFP) which identifies the efficiency with which all factors of production are deployed to create output.

There is general acceptance of these four salient facts, but little agreement about the underlying causes of the productivity decline. Most explanations have some traction, but not much. What is becoming clear is that the crisis may have persistent effects on the UK’s productivity due to reduced investment in physical and intangible capital, and impaired resource allocation. These factors seem to account for a sizeable part of the productivity shortfall relative to pre-crisis trends.

In the longer run, the productivity trends are likely to reflect the long tail of poorly performing firms that the UK has been noted for over many years. Some of this is due to structural factors such as ‘poor management’. Perhaps the problem is compounded by policy choices: governments have traditionally been reluctant to interfere with managers’ right-to-manage, even when those managers appear poorly equipped for the job. By contrast, some of those countries with much higher productivity levels have much greater levels of state intervention and, in some cases, strong industrial strategies supported by government.

Despite this, there are some areas where optimism is merited. London is a global centre, one of only a few truly international ‘hub’ cities benefiting from agglomeration and networking. It continues to thrive and prosper, offering safe haven for international capital, migrant labour flows and talented entrepreneurs. More broadly, a number of reforms have been undertaken since the 1980s that have provided a foundation for a continuation in the long-term productivity catch-up that the country began relative to its competitors in the 1980s.

These reforms include the expansion of higher education, reforms to welfare systems and labour law, and deregulation of capital flows. The UK has invested very heavily in human capital via growth in participation in higher education. Reforms in other areas, such as the welfare system and labour law, also provide a flexible labour market capable of absorbing future shocks, while the deregulation of capital flows and a relatively liberal immigration policy ensure the free flow of capital and labour. It remains to be seen whether the UK can benefit from these good foundations to make up the ground it has lost in recent years.

Note: This article is based on Bryson, A. and Forth, J. (2015) ‘The UK’s Productivity Puzzle’, NIESR Discussion Paper No. 448 and CEP Occasional Paper No. 45. The final version will appear in ‘Productivity puzzles across Europe’, P. Askenazy et al. (eds), forthcoming.

This blog also appears here.