A divided country? As Westminster squabbles, Britain’s economic disparities are left unresolved

With all eyes on the current Brexit mess, we have been devoting less attention to the economic and social divisions that led to the Referendum in the first place. While some academics have described this as ‘the revenge of places that don’t matter’, it is a rather unfortunate situation, as disparities are likely to be exacerbated by Brexit.

With all eyes on the current Brexit mess, we have been devoting less attention to the economic and social divisions that led to the Referendum in the first place. While some academics have described this as ‘the revenge of places that don’t matter’, it is a rather unfortunate situation, as disparities are likely to be exacerbated by Brexit.

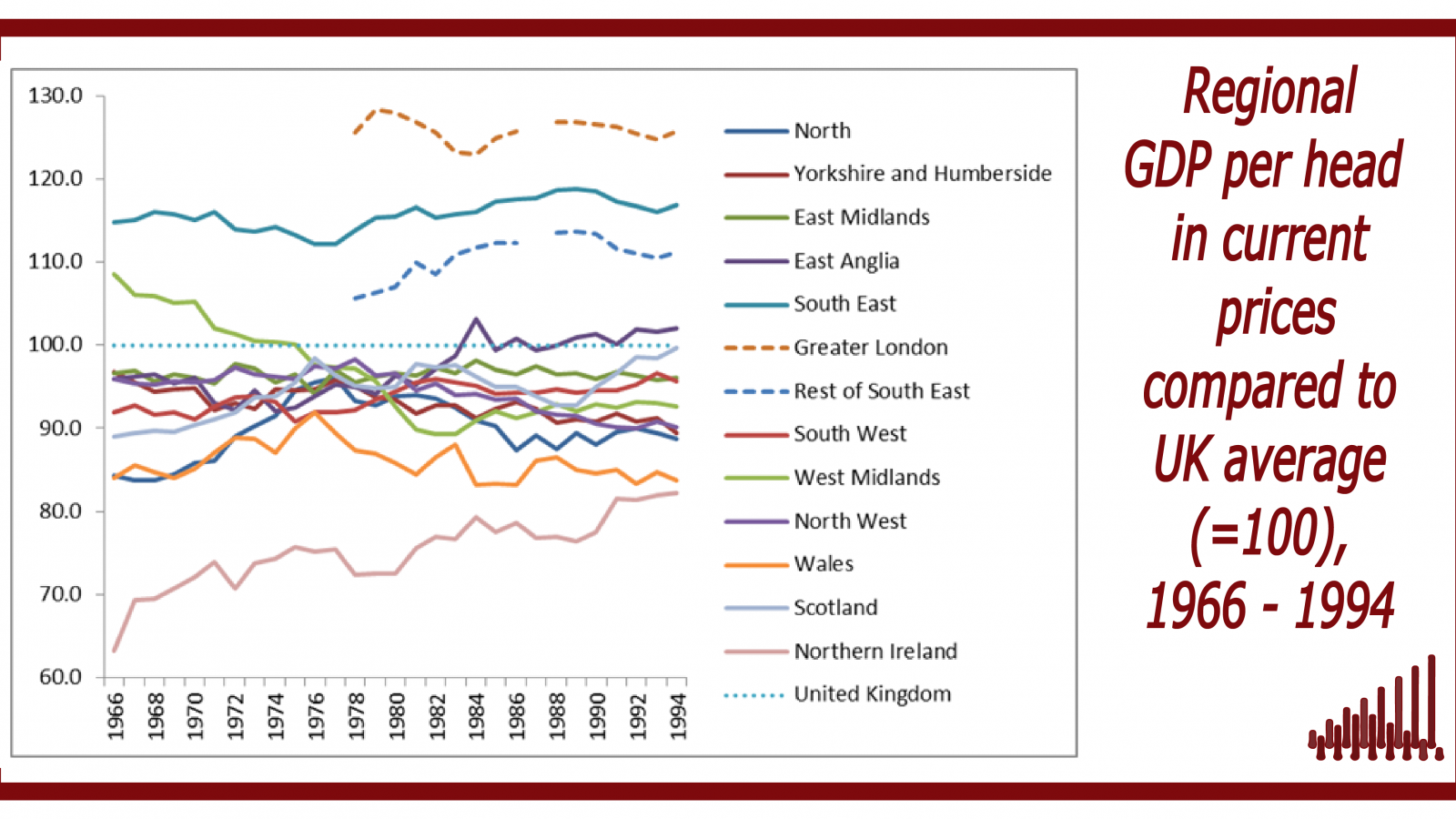

Recent research shows that the UK now has some of the largest regional disparities among OECD countries. In a policy paper published this morning I take a historical perspective and explore the evolution of regional economic disparities in the UK. Based on data going back to the 1960s I show that economic disparities had been declining until the late 70s, after which the gap widened again.

The South-East of England generated more than one third of economic activity in 1966 and continues to do so today. Northern Ireland and Scotland have improved their relative economic performance. This leaves Wales and some English regions that experienced no change or a decline in their share of the national income.

Similar patterns hold for differences in labour productivity (Gross Value Added -or GVA- per hour worked). Strikingly, 72% of regions (based on NUTS-3 classification) have productivity levels below the national average. Since we know that productivity is the only source for long-term economic growth and development it is crucial to address this spatial productivity gap. Here, agglomeration economies, or the concentration of industrial activity, plays a crucial role, which is notoriously difficult to influence with policies, though some evidence exists.

These trends are extremely relevant in the current political context as disparities between places have been shown to be a major driver of the Brexit vote. My paper raises a few points for policymakers to consider when designing a National Spatial Policy:

- Regional economic disparities in the UK are a longstanding issue, but the question is whether they are driven by London’s overperformance or by the underperformance of the rest;

- Labour productivity differs vastly across regions. The majority of places in the UK have an output per hour worked that is below the national average;

- Since disparities are relative by definition, regional development needs to be based on a politically-agreed benchmark or goal. This can be a long-term vision of the region itself;

- Any long-term policy vision needs to be fully aware of the importance of agglomeration economies as a fundamental driver in shaping places and regional development;

- Finally, access to digital infrastructure and skills (or the lack of thereof) will play an increasingly important role in defining regional economic disparities.

While the full extent of the negative implications ultimately depends in the deal the UK chooses, we know that regions will be impacted differently. Some research shows that voters in less prosperous regions that depend more on EU membership were more likely to vote for Brexit. If Britain doesn’t start to address regional economic disparities all the political turmoil we’re living through may well have been for nothing.