Effective COVID-19 policy is not only about public health, but also about economics

The COVID-19 crisis has upended the lives of many, causing almost 200M global infections to date, over 4M deaths and untold damage to the livelihoods of millions. Although the recent vaccine rollout in some parts of the world offers some room for optimism, the epidemic is still far from defeated and many in the developing world are still at significant risk of infection.

The nature of the crisis, ostensibly one related to public health, has proved to be multi-pronged, with economic and social behaviour, public health policy and economic policy closely intertwined and both reacting to and conditioning the future path of the epidemic.

The COVID-19 crisis has upended the lives of many, causing almost 200M global infections to date, over 4M deaths and untold damage to the livelihoods of millions. Although the recent vaccine rollout in some parts of the world offers some room for optimism, the epidemic is still far from defeated and many in the developing world are still at significant risk of infection.

The nature of the crisis, ostensibly one related to public health, has proved to be multi-pronged, with economic and social behaviour, public health policy and economic policy closely intertwined and both reacting to and conditioning the future path of the epidemic. The policy challenges posed by the epidemic were well articulated by NIESR’s Director Jagjit Chadha in his Review’s Commentary earlier this year.

The severity and characteristics of COVID-19 have meant that people have spontaneously and voluntarily changed how they work, shop and socialise. In turn, these decisions have had severe social and economic consequences, with many businesses struggling to stay afloat in an environment where customers have feared and avoided crowded spaces such as retail, hospitality and public transport. As expected, most governments have sought to actively intervene and cushion people and businesses against the worst fallout from the epidemic. Yet, many governments have struggled to understand who to ask for advice and even to formulate the kind of expertise needed to navigate the crisis.

As a point in case, the government of the United Kingdom has been advised primarily by three different sets of experts, namely the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling (SPI-M), the Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviours (SPI-B) and HM Treasury, respectively. SPI-M, a subgroup of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) consisting of technical epidemiologists and modelling experts, have provided forecasting and decision support to the government by considering and simulating different possible scenarios, based on complicated mathematical models of the epidemic.

Notably, the models considered by SPI-M are largely mechanistic, non-behavioural models that do not explicitly model behaviour, but only takes it into account indirectly. In addition, the remit of SPI-M disregarded the effects of different public health measures, such as social distancing and lockdowns, on the overall economy. In fact, it appears that economic considerations were specifically disregarded in advice formulated by SPI-M. The minutes of the SAGE meeting on September 21, 2020 state that ‘Policy makers will need to consider analysis of economic impacts and the associated harms alongside this epidemiological assessment. This work is underway under the auspices of the Chief Economist’. Yet at a November 11, 2020 meeting of the Treasury Committee, the Chief Economist confirmed that that HM Treasury in fact did not consider any likely impacts of lockdown measures on either the epidemic or on the economy. On May 26, 2021, Dominic Cummings again confirmed that no economic analysis of lockdowns was carried out.

SPI-B, another subgroup of SAGE, was tasked with considering the behavioural aspects of the crisis. Consisting primarily of behavioural scientists and psychologists, this group considered how different policy measures would likely be received by the public and how different policy interventions should be presented. Although grounded in empirical and theoretical work in behavioural sciences, the advice given by SPI-B appears not to have been directly integrated into the epidemic modelling carried out by SPI-M, but rather was considered by decision makers alongside the modelling advice. In addition, SPI-B was not tasked with determining the aggregate consequences of behaviour on either the path of the epidemic nor on the likely impact of behaviour change on the macroeconomy.

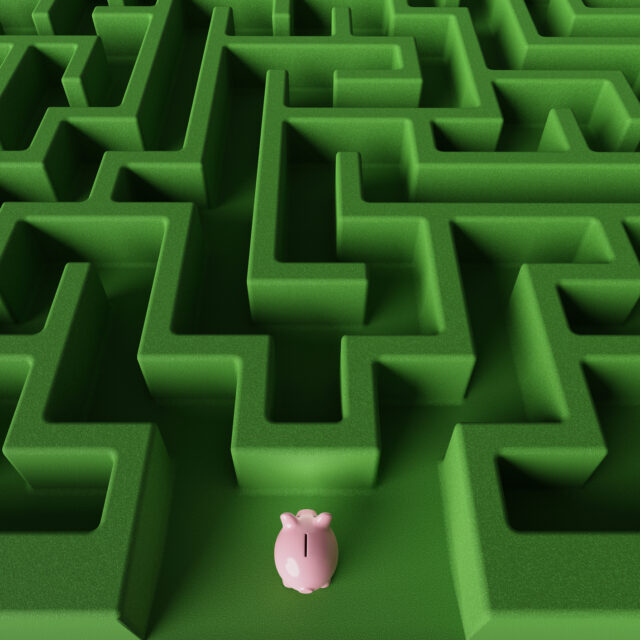

Last, economists working at HM Treasury were tasked with looking after the economy. Reportedly, the Treasury has scarce direct input from either SPI-M or SPI-B and thus treated the epidemic as something “exogenous” to the economy, i.e. as something that influences the economy but that is otherwise separate from the economy. This seems to have led the Treasury to design economic policies without an eye on the likely spillover effects of such policies on the overall effort to control the epidemic through public health measures. The apparent tension between different parts of government, exemplified by public statements from the then Minister of Health Matt Hancock and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, have further strengthened the impression of a decision-making process in which ‘all bases’ seemed to be covered in terms of scientific expertise, yet the structure of the process has created silos of knowledge that have made a proper holistic approach to managing the crisis difficult to achieve.

The lack of coordinated thinking became evident in an interview of the then health secretary Matt Hancock in March 2021. In it, he stated that ‘You have to balance all the different considerations. It’s only at the prime minister’s desk that all these different considerations come together. […] I’m responsible for the health aspects and then the huge economic response the chancellor is responsible for’.

What then, would such a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to the crisis have contributed to the formulation of policy? There are several key insights, all central to the interdisciplinary field of economic epidemiology, that would have contributed to better decision making.

- In important respects, infectious disease epidemiology and public health are closer to the social sciences than to cognate fields such as biology and medical sciences. This is because disease spread in human populations depends on people’s decisions in addition to the biological properties of the disease. This means that in order to understand and predict the spread of the disease, modelers need to understand both how individuals make decisions (and their incentives to act in the way they do) and how such individual decisions interact with those of others. In addition to yielding better predictions of how the disease spreads, understanding behaviour and incentives is fundamental for formulating policy. For if policy makers do not understand how different interventions are likely to change behaviour, on what basis can policy be formulated in the first place? Forecasting, impact studies and best practice cannot be replaced by good intentions and wishful thinking.

- As explained above, the characteristics of COVID-19 and the initial lack of pharmaceutical products such as vaccines and antivirals meant that governments have largely depended on non-behavioural interventions (NPIs) that modify or directly control behaviour and contact patters in the population. Together with spontaneous changes in behaviour, this has meant that the COVID-19 crisis has not been confined to merely one of health but has indeed had profound repercussions on social and economic life. For that reason, economic and public health policies must be considered in tandem, with a view to achieving desirable outcomes overall. In other words, public health measures must be recognised to have economic impact and economic policies, such as furlough schemes, statutory sick pay and support for self-isolation, must be thought of as measures that directly support public health measures designed to control the spread of the disease. In practice, both sets of policies seem to have been formulated in isolation and only been considered together once they reached the PM’s desk.

- Next, not all public health measures are equally desirable and the composition of desirable measures may change across the stages of the epidemic. For example, it is possible (and even likely) that an effective test-trace-isolate infrastructure at low levels of disease prevalence in the population can obviate more intrusive and damaging lockdown measures that will be necessary at higher levels of disease prevalence. In order to better understand the trade-offs involved in economic-epidemic policy making and to aid in the systematic search for good policies, an integrated analytical framework for decision making and policy formulation is needed. Fortuitously, many of the ideas necessary for building such a framework already exist in the form of economic epidemiology.

- Last, in order to formulate policy and to communicate this to the public, decisions should ideally be formulated with the aid of a fully dynamic, economic-epidemic cost-benefit analysis. Government policy making is routinely submitted to the discipline of cost-benefit analysis, with robust and theoretically underpinned principles outlined in the so-called Green Book. The Green Book contains a number of principles that are key to ascertaining different policy interventions, such as how to deal with illness, mortality, long time horizons, uncertainty etc. The lack of a credible cost-benefit analysis has not only hampered effective government decision making and policy formulation. It has also created unhelpful and unnecessary social tension between different stakeholders such as groups at risk of serious illness from infection on the one hand and business owners and the self-employed on the other. With a clear and transparent cost-benefit analysis, the rationale for different interventions could have been more easily expressed and communicated. Supplemented with a properly thought-out set of economic support schemes designed to provide correct incentives to reinforce public health measures, such an analysis may have gone some way to create a sense of common purpose during difficult times.

Common for all these insights is that they rely on complicated two-way interactions between disease dynamics and economic dynamics. In addition, they rely on how people’s incentives change behaviour and on how policy interventions change trade-offs and therefore can be expected to lead to different outcomes, epidemiological as well as economic. Economists working in the field of economic epidemiology (or the economics of infectious diseases) specialise in exactly this type of interactions. As is commonplace in economic modelling, economic epidemiologists explicitly consider individual behaviour and decision making in formal models of disease propagation akin to the mechanistic models studied by researchers at SPI-M. But rather than looking at non-modelled behaviour and relying on behavioural insights in parallel to the modelling as is done by researchers at SPI-B, economists make the behaviour an integral part of the formal modelling.

They do so by using a combination of techniques, including decision theory, game theory and different techniques from dynamic optimisation (such as dynamic programming and optimal control theory). Furthermore, economists use techniques borrowed from other domains of economics to inform public health policies themselves, such as the optimal design and use of test-trace-isolate, lockdowns, mass testing etc. Notably, by doing so economists directly inform public health policies and not merely the economic consequences of such policies. And by doing so, they also are ideally placed to think about how different economic policies help or hinder the implementation of said public health measures.

In addition to using economic ideas to inform public health policies, economists have also been very actively involved in the empirical study of the epidemic, including in the assessment of the effects of different policies to control the spread of the disease and in determining the role of voluntary behaviour changes and mandated restrictions to activity in causing economic damage. Because economists have developed empirical techniques tailor made to understand data that concern itself with behaviour and policy interventions, they have found fruitful application in understanding policy and behaviour during the epidemic.