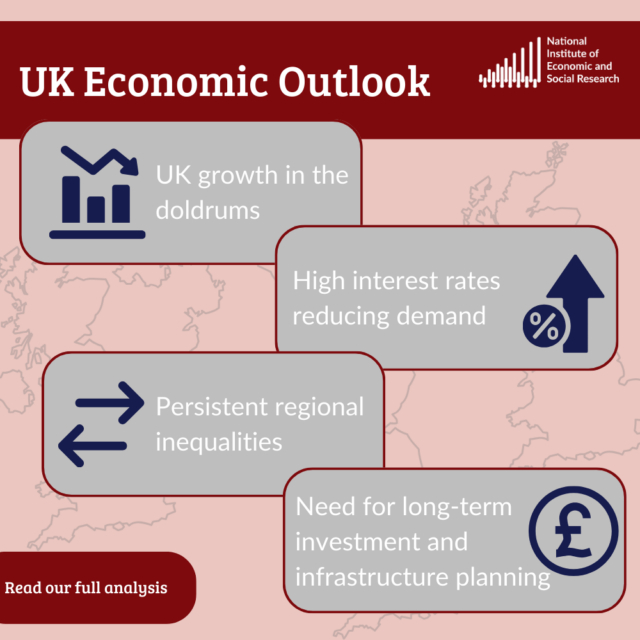

Friday Flyer: Why Growth Matters

Why does long growth or what economists used to call secular trend matter? It is essentially about compound interest. At a growth rate of 2% per year, income will double every 35 years. Over the 315 years from 1700 to 2015 in the UK we have reasonable or passable data for Britain stating that income has grown at an average rate of 1.69%, which implies a nearly two hundred-fold increase in income (widget production) over this long period.

Why does long growth or what economists used to call secular trend matter? It is essentially about compound interest. At a growth rate of 2% per year, income will double every 35 years. Over the 315 years from 1700 to 2015 in the UK we have reasonable or passable data for Britain stating that income has grown at an average rate of 1.69%, which implies a nearly two hundred-fold increase in income (widget production) over this long period. Had income grown at just 1% per year on average, there would have been an increase of some 22 times only and income would be barely a fifth of what it is now. The numbers are slightly different when we examine GDP per head, with a 30 fold over the period covering the beginning of the industrial revolution in 1760 to 2015, but if we had grown at the lower rate our income per head would be under a fifth of its current level and we would be somewhere around the level of countries such as Bolivia or Ukraine.

It is therefore not really year to year growth that matters but the trend. If we strip out recession years, growth in those years was 2.6% on average and certainly drew a lot of attention from commentators. And if we look at years of boom, which I casually define as over 2.5%, average growth in those years has been 4.7% and again these years because they are not normal gain much attention. Much modern macroeconomic work has proceeded by thinking about the business cycle as a direct consequence of the growth process. And we have thought about how to offset the implications of business cycles that are the result of changes in optimal choices. Unsurprisingly perhaps there has been relatively little for policymakers to do. Inside this kind of analysis is that most fluctuations are about movements to a better set of outcomes, perhaps through creative destruction. But this short run analysis by examining the tail of the dog may have tended to miss the big story. And so it may pay to return to the question of long run growth rather than business cycles.

When we try to account for this long run growth what we do is to attribute the overall increase in income or production to two factors of productions, capital or labour, and then allow something called total factor productivity to explain the rest. This is the famous residual of Bob Solow, which is still used to drive most macroeconomic stories about business cycles and growth. For Britain over this long period, we find that increases in labour inputs explain around 20% of the change in income, that capital explains around 35%, leaving around 45% explained by the magic of total factor productivity. If we instead examine income per worker, which is a better measure of welfare, then we find that some 35% can be explained by capital accumulation, also known as investment, and some 65% by total factor productivity. It is perhaps no great surprise that efforts to maximise growth, over successive generations and in many countries has returned repeatedly to the question of investment, which comes from savings, and productivity.