Hard Choices: the Political Economy of Trade Policy after Brexit

Brexit will require the UK to change its international trading relations. New norms will need to be established both for trade with continental Europe and other trading partners. New partnerships will need to be established. The UK may no longer remain a member the European Customs Union and the Single Market and may not be able to rely on trading arrangements that have been built up through membership of the Union or Single Market. The gravitational pull of the European market will remain.

Brexit will require the UK to change its international trading relations. New norms will need to be established both for trade with continental Europe and other trading partners. New partnerships will need to be established. The UK may no longer remain a member the European Customs Union and the Single Market and may not be able to rely on trading arrangements that have been built up through membership of the Union or Single Market.

The gravitational pull of the European market will remain. However, if the UK ceases to be a member of the European Union Customs Union and Single Market, and customs tariffs and other regulatory restrictions are imposed between UK and EU producers and consumers, trade will become far more difficult than people on either side of the Channel are accustomed to. This will raise business costs, add to commercial risk and witness the introduction of trade barriers traditionally associated with hard borders between countries. The UK will become more reliant on the effective functioning of the global trading system administered by the WTO, its capacity to produce goods and services required by global markets and its capabilites to effectively trade in those markets.

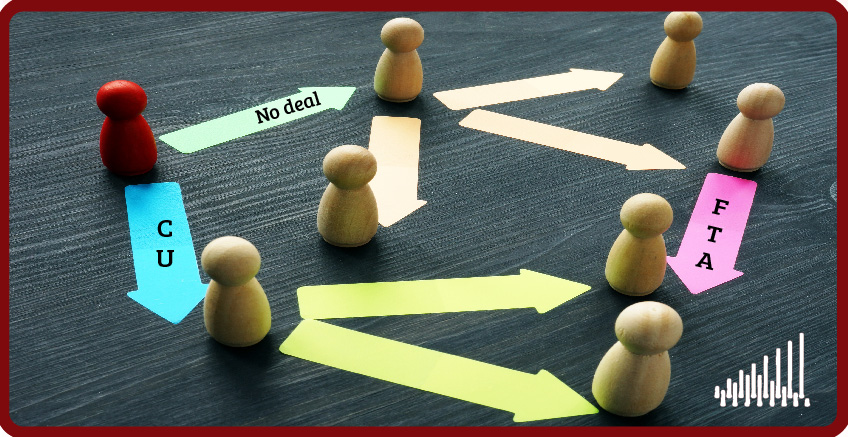

As we recently explained in our article with Anne Williamson in the latest NIESR Economic Review, the UK faces no easy options in determining how to develop its approach to international trade post-Brexit. If it does indeed leave the European Customs Union and Single Market, it faces the possibility of:

- simply crashing out of the EU without a deal and withdrawal into a protectionist environment;

- trying to form market-access agreements and Free Trade Areas (FTAs) with the EU and other countries (this was the policy of the Theresa May government);

- or unilaterally reducing tariffs and liberalising trade with all countries.

Each course raises significant practical difficulties, and entails major disadvantages compared with staying in the Customs Union and Single Market.

The economic costs of a “no-deal” approach stand to be very large, including inevitable tariffs that raise costs to producers and consumers, obstruction of UK access to EU markets, physical disruption at borders, a damping of investment and the much-discussed problem of the Irish border. Assuming “no-deal” does not happen, negotiating FTAs with countries outside of the EU would be possible only after a lengthy transition period, as in the Withdrawal Agreement voted down in Parliament, and would depend on the shape of the ultimate post-Brexit trading relationship between the EU and UK. This process: would be difficult, costly, and protracted; would likely be concluded on disadvantageous terms because the UK is small on its own; would be even harder to apply to trade in services; and would yield extremely small gains given the volume of UK non-EU trade that is already covered by FTAs to which the UK is currently a party through its membership of the EU.

Finally, instead of attempting to form independent FTAs, the UK could reduce its own tariffs and liberalise its own borders with all countries, and in so doing, lower the cost of imported goods to producers and consumers, and open up its trade with the rest of the world. Unilateral liberalisation would still face the same problems of loss of preferential access to European markets and disruption to cross-Channel trade. It would entail severe economic costs of adjustment, particularly for those activities most heavily protected by EU trade and regulatory policies, and those activities integrated into UK-EU supply chains, including in agriculture and processed agricultural products, wearing apparel and motor vehicles. Unilateral liberalisation would afford only very gradual gains.

Whatever, the final form of Brexit and arrangements negotiated with its co-located trading partners in the EU, it will not be business-as-usual in the UK economy in the post-Brexit world – unless the UK remains a member of the European Single Market and Customs Union. This world will be further complicated by evolving trading arrangements (and tensions) between the UKs current and potential trading partners.

In this uncertain and evolving trading environment, the UK needs to conduct a much more profound and considered debate on these issues before deciding to set aside the large benefits of membership of the Customs Union and Single Market for the significant difficulties and tenuous gains offered by the alternatives. Public debate on the economic and social effects of trade policy has so far lacked the detailed but necessary analysis of these questions. It seems essential to establish a national policy review institution, modelled on the Australian Productivity Commission, in order to stimulate such a debate. The UK would also be well served by joining with coalitions of like-minded countries to promote the liberalisation and continued development of international trade, and to defend the global trading system.

David Vines is Emeritus Professor of Economics, and an Emeritus Fellow of Balliol College, at the University of Oxford.

Paul Gretton is an Associate at the Centre for European Studies, Australian National University.

All views expressed are those of the authors. You can read the full article here.