Levelling Up or Regional Regeneration

Our Director talks to Adrian Pabst to discuss how the Covid-19 pandemic has further exposed regional imbalances

Adrian Pabst leads our work on household and regional analysis, as well as the institutions of government. One of the primary failures of British economic and social policy in the post-war period has been the persistent emergence of a regional divide. This emerges time and time again in our work for our Outlooks, the Productivity Commission and just prior to the Covid-19 crisis I highlighted this problem in an article for the Independent. I wanted Adrian to help us understand better where we were now placed as we head into 2022.

How has the Covid crisis exposed our regional imbalances?

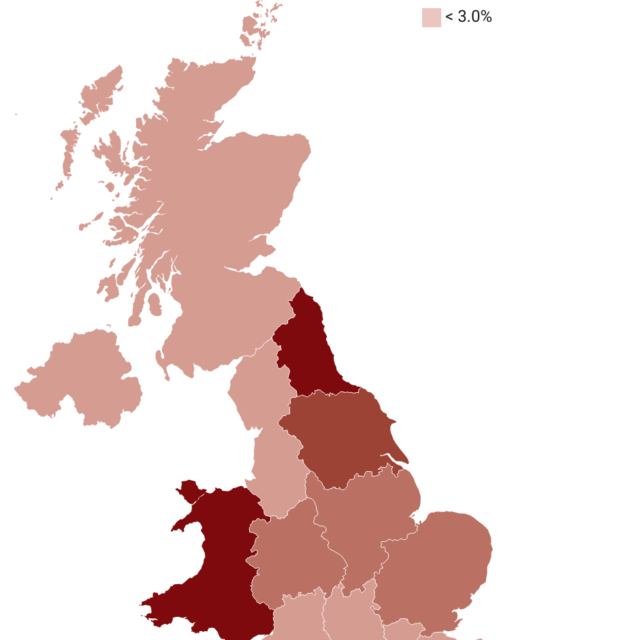

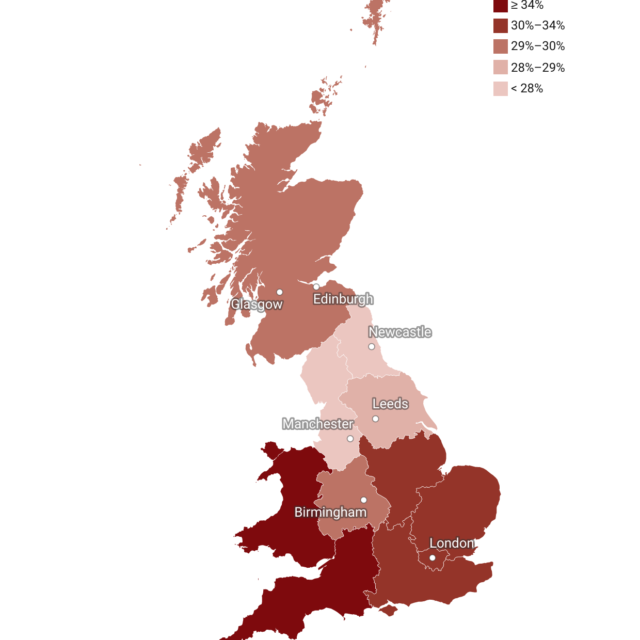

The UK has some of the worst spatial inequalities among the OECD’s 38 advanced economies. This means there are worrying levels of imbalances both between and within regions in terms of health, wealth and social well-being. When the pandemic struck last year, we initially saw a slight reduction in those imbalances, as London took a bigger hit than other parts of the country in terms of rising unemployment and falling economic output and labour productivity.

But as the recovery got underway this Spring, regional inequalities have once again widened – with London and the metropolitan South-East performing much better than the rest of the country. The Covid-19 crisis has revealed a deepening disparity and an increase in both wealth and income inequality, including a disturbing rise in levels of extreme poverty in regions such as the North-West. Existing imbalances and health inequalities in structurally weaker regions and low-income households have been exposed.

The government wishes to level up, what does that mean?

Until recently ‘levelling up’ was a catch-all phrase to describe the Government’s intention to reduce regional disparities and provide opportunities more equally across the country. A month ago or so, Neil O’Brien – the minister for levelling up defined the Government’s plans in terms of four goals:

- to shift power to local leaders and communities;

- to support the private sector in order to grow the regional economy and raise living standards;

- to spread opportunity and improve public services; and

- to restore local pride and civic cohesion.

That is a vast, ambitious agenda, which brings together both economic and social aspects of spatial inequalities, and the White Paper (which is slated for publication in the New Year) will tell us more about how the Government intends to turn these ideas into reality. So far, the dominant response has been to throw money at the problem by allocating the Towns Fund to constituencies newly won by the Conservatives at the 2019 election. A one-off grant from the Treasury will provide little more than a sticking plaster for deprived parts of the country. Regional regeneration will not happen unless the White Paper sets out some transformative change with a sustained agenda implemented in the medium to long run.

What would you like to see in the New Year from the White Paper?

Three things are vital for sustained regional regeneration. First, a long-term strategy that combines a holistic approach with the right scale of investment – instead of a patchwork of policies and endless churn, as we have seen for decades. This means No 10 will have to overrule the Treasury’s refusal to commit new spending. For example, £3 billion pledged on skills over the next three years is not much of a ‘skills revolution’ as it barely returns expenditure to 2010 levels.

Second, the UK is in dire need of some institutions with a long-term outlook that can foster and support private and public investment. The National Infrastructure Bank located in Leeds is a start, but there is a missing link as we need a remit that goes beyond infrastructure. A National Development Bank has served thriving economies such as Germany and South Korea well. Britain would also benefit from regional and sectoral banks and a much stronger provision of technical training through vocational colleges.

Third, if levelling up is to gain momentum and change conditions for people in the communities where they live, it has to involve local design and delivery; knowledge about local needs is key, as is accountability to local citizens.

How would you reform local democracy to support regional regeneration?

Local government is emasculated and emaciated, lacking the power and resources to address the deep gaps in local and regional capital markets and labour markets. Little wonder that over two-thirds of all Foreign Direct Investment and venture capital flow into London and the metropolitan South-East.

To start rebuilding local government capacity to regenerate the regions, two reforms are needed. The first is to provide revenue streams that are not directly controlled by the Treasury. Business rate retention is too limited and benefits already affluent parts of the country. While the government’s pledge in the October 2021 budget to increase local government expenditure by 3 per cent is welcome, it does not begin to compensate for the cuts since 2010 and the rising costs associated with social care.

The second reform is to enhance the accountability of local government to their citizens and not simply to central government. Whether directly elected mayors or more popular participation in fundamental budget choices, local authorities should be more accountable to the people who elect them rather than officials in Whitehall. That does not imply a politicised system of US governors, but could take the form of either elected mayors as in France or in Germany. Regional regeneration means a new form of local democracy.