Low aspirations don’t explain why white working class children fall behind

The lower educational achievement of white working-class pupils has long been recognised as a key challenge for schools. But in recent years, the yardstick against which their under-performance has been measured has changed – from middle-class pupils to children from ethnic minorities. This is due to evidence that pupils from ethnic minorities, including recent migrants and those with English as a second language, have been increasingly outperforming white working-class pupils.

The lower educational achievement of white working-class pupils has long been recognised as a key challenge for schools. But in recent years, the yardstick against which their under-performance has been measured has changed – from middle-class pupils to children from ethnic minorities. This is due to evidence that pupils from ethnic minorities, including recent migrants and those with English as a second language, have been increasingly outperforming white working-class pupils.

In a new report to the Department for Education, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research reviewed the evidence on strategies that have been undertaken to boost the attainment of ethnic minority and migrant pupils at school. The idea was to identify interventions and approaches that might also be effective to help white working-class children.

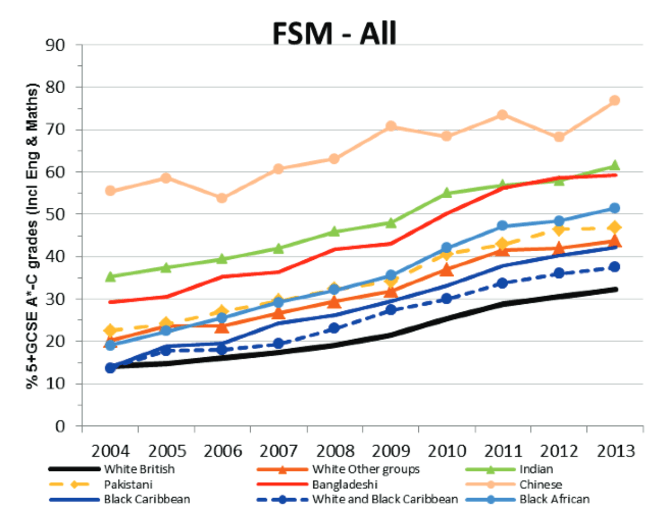

In the education world the term working-class is often used in relation to pupils who are eligible for free school meals, so the term refers to pupils from poor families rather than directly to socio-economic status. Research undertaken by Steve Strand, published alongside the NIESR report, provides analysis of recent trends in attainment by ethnic group and deprivation. This shows that in 2013, among pupils eligible for free school meals, not only were all ethnic minority groups outperforming white working-class pupils at GCSE, but the gap between the two groups had increased, as ethnic minority children’s performance improved more rapidly. And while much concern has been focused on white working-class boys, girls also show low levels of attainment.

GCSE attainment for children entitled to free school meals, by ethnic group in 2004-2013. Strand (2015), Department of Education, research report

Do aspirations explain underachievement?

The performance of ethnic minority and migrant children has been found to explain the “London effect” – that children in London do better than their peers in other parts of the country. In his report, Simon Burgess from the University of Bristol said:

The children of relatively recent immigrants typically have greater hopes and expectations of education, and are, on average, consequently likely to be more engaged with their school work.

Burgess believes that it is parents and pupils who have made the real difference to London schools, rather than education policies and practices. Existing research supports his conclusion, pointing to the importance of both the home and the school on pupils’ attainment. The contribution of schools to children’s performance has been found to be relatively smaller than those of the parent, family and pupil themselves.

The term “aspiration” is frequently used by researchers, distinguishing ethnic minority children and families with their “high” aspirations, from white working-class families, with their “low” ones. But there is limited evidence on how these strong or weak aspirations actually affect attainment. Some evidence suggests the opposite – that the aspirations of working-class parents are not low. They just don’t have access to the necessary information, knowledge or resources to support their children’s learning.

At the same time, there is reasonably strong evidence that parents from some ethnic minority groups are more likely than white working-class parents to engage in certain behaviours, such as become involved in their child’s school and use private tutors.

We need to know more about why white working-class parents tend to behave differently. It’s possible that these parents may not have good memories of their own school days and their only contact with their child’s school may be when a problem arises.

In recognition of this, and the importance of parental engagement to pupil achievement, some schools are developing strategies to connect more with parents. For example, Graveney School in South London, now aims to establish strong relationships with all families and children who qualify for the pupil premium, which includes those on free school meals, before they join the school. The school’s GCSE results for its pupils on free school meals are higher than children not on free school meals in other schools.

The role of the school

While families are paramount, research has suggested that a number of school practices may be effective in raising the attainment of both ethnic minority and white British pupils. These include high-quality school leadership and a school ethos that values diversity and has high expectations of all pupils. Schools that monitor and track pupils, have a flexible and inclusive curriculum and engage with parents and the wider community also help children do better.

Clearly, pupils with English as an additional language are at an initial disadvantage and need support to learn. Yet such pupils generally catch up, as research by Surrey’s Sandra McNally and her colleagues has shown. White British pupils obviously speak English, but consistently underperform in language and literacy and may not be getting the help they need.

Disadvantage is already very apparent at five-years-old. Efforts to raise attainment of white working-class pupils need to consider what works for even the youngest pupils. Targeted interventions in the early years – such as extra language and literacy lessons for children from disadvantaged homes – could help ensure that the gap narrows rather than, as at present, widens.

This blog was first published by the Conversation on 26th June 2015

The NIESR research discussed in this blog was undertaken by Lucy Stokes, Heather Rolfe, Nathan Hudson-Sharp and Sarah Stevens.