Our housing crisis – not market failure: persistent policy failure

With housing nothing seems to change. This is what I wrote in 1999:

“Concerns [about rising house prices] focus on the short term symptoms but it is really a long term problem. The constraints policy applies to the most basic attribute of housing – space – remain the same…When … the National Playing Fields Association complains that – despite government assurances to stop the sale of school playing fields for development - another 80 went last year, it is the flip side of the same coin (see here for a more recent example).The amount of land made available for development is decided in physical units and is intentionally highly constrained by the planning system. But market forces allocate the land that is made available. So developers bid up its price. In turn this creates an incentive for cash strapped councils to sell off any land they own. Since people regard space not only as desirable but – like health care, eating out or short breaks – something they want to buy more of as they get richer, the price of space inevitably goes up.”

With housing nothing seems to change. This is what I wrote in 1999:

“Concerns [about rising house prices] focus on the short term symptoms but it is really a long term problem. The constraints policy applies to the most basic attribute of housing – space – remain the same…When … the National Playing Fields Association complains that – despite government assurances to stop the sale of school playing fields for development – another 80 went last year, it is the flip side of the same coin (see here for a more recent example).The amount of land made available for development is decided in physical units and is intentionally highly constrained by the planning system. But market forces allocate the land that is made available. So developers bid up its price. In turn this creates an incentive for cash strapped councils to sell off any land they own. Since people regard space not only as desirable but – like health care, eating out or short breaks – something they want to buy more of as they get richer, the price of space inevitably goes up.”

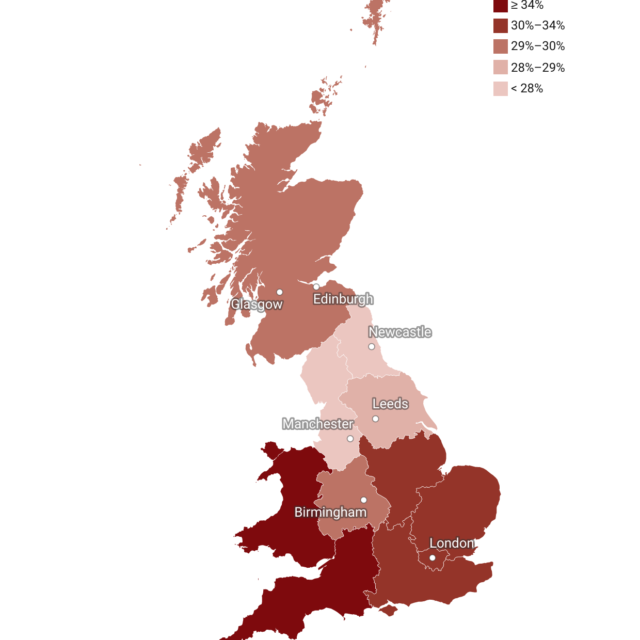

Since 1955 the price of housing in real terms has risen 5-fold but the price of land to put houses on has gone up 15-fold. Housing was thought to be unaffordable in 1999: the only difference now is that the official measure shows it is half as affordable as it was then.

My article in the current Review spells out the reasons why policy so severely and over such a long period has systematically restricted the supply of space for houses and made housing supply almost completely unresponsive to prices.

The problem is not only the way our planning system works: but that is the main problem. Of course we need planning and land market regulation. One of the many contributions good planning should make is to keep beautiful countryside and coastline free from development and protect green open spaces. Markets would not work effectively. The result would be that where development was prevented to preserve amenities, land prices would rise.

But there is a world of difference between that and a blanket restriction on development more or less everywhere people want to live or firms locate. And that is what we have been doing since Greenbelt boundaries were first imposed in 1955 and land for development became allocated not on price, not even taking any account of price, but on the basis of assessed ‘need’: with need estimated on the basis of poor projections of local growth in household numbers. So policy intentionally prevents development everywhere people most want to live and would be most productive – in great swathes of land surrounding our major cities. And the mechanism we use to decide how much land to allow building on, systematically under-supplies it because it takes no account of rising incomes. And as we know the demand for housing space is mainly driven by income growth not numbers of households.

So really no surprise at all that housing has become more and more unaffordable, the young have been progressively excluded or forced to live with parents, housing has been transformed into an asset – rather than just somewhere to live – and the old and rich have hugely benefited. And since the rich tend to be influential and the old vote, politicians are reluctant to tackle the problem in any way that could be effective.

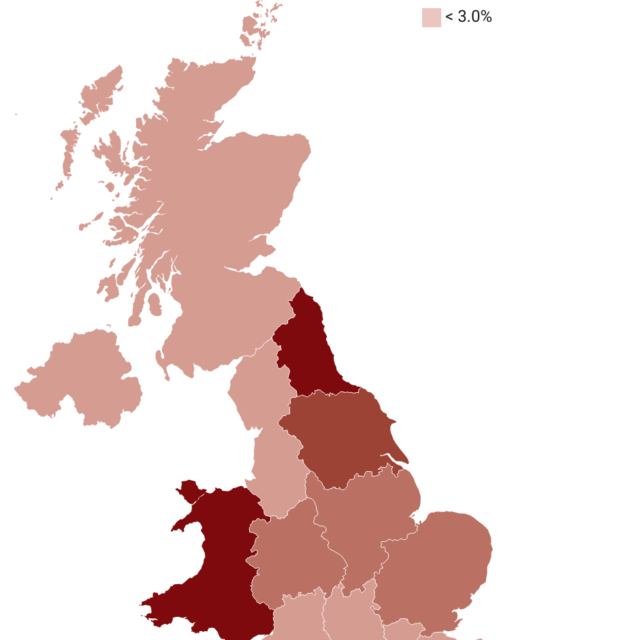

There are many reforms that could work. Despite rhetorical ‘small island’ claims, there is no actual shortage of land. Greenbelts, for example, occupy getting on for 1.5 times as much land as all urbanised areas put together; just within London about 23 percent of the land is Greenbelt and London’s Greenbelt extends from the North Sea coast to Aylesbury. Only 4.7 percent of the whole of the South East has any building of any kind on it.

It may be called ‘green’ but much land in the Greenbelt is far from green and has no public access anyway. The biggest single land use in our Greenbelts is intensive arable – 74 percent of Cambridge’s Greenbelt: far from green. There is enough land in London’s Greenbelt within 1km of a station and which has no environmental or amenity value for a million homes: a million more homes within easy reach of some of the most productive jobs in Europe in locations where house prices tell us people really want to live.

The issue should not be the simplistic designation of land as Greenbelt or Brownfield but the value of the land to the community in its present use compared to its value for housing. Policy should focus on preserving valuable habitats, improving the bio-diversity of land, preserving land with public access and scenically valued land. In summary – there is a strong welfare economics case for preserving large tracts of land in an unbuilt state, especially where there is public access or it has special habitat value; but no case for blanket restrictions on development more or less everywhere.

We all want incomes to rise. That means we have to accept that the demand for houses and particularly housing space, will continue to rise and unless we supply enough space the problems in the housing market, and likely the British economy, will become completely unmanageable. And in the long run the outcome – already highly inequitable – would be catastrophic.

Paul Cheshire is Professor of Economic Geography at the LSE. All views expressed are those of the author.