Uncovering Scotland’s Productivity Performance

The UK government’s ‘Plan for Growth’ raises questions about how it intends to boost productivity and reduce inequalities both between and within the country’s regions. Speaking to Professor Adrian Pabst, Ana Rincon-Aznar – a Principal Economist in the Public Policy team – explores some of the findings from her latest research into productivity in Scotland.

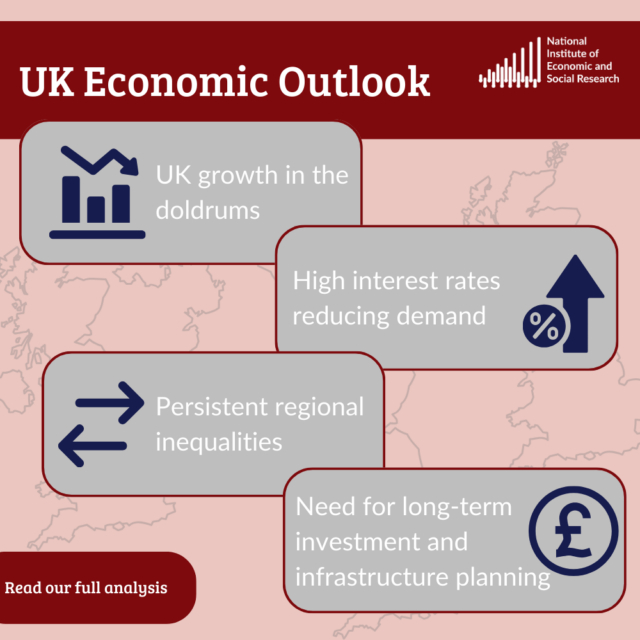

This research on productivity in Scotland is part of an important body of work at the Institute on the causes of the UK’s poor productivity performance and the drivers of differentials in regional productivity growth. As a major partner in The Productivity Institute, whose mission is to improve our understanding of the productivity slowdown and help design policy solutions, NIESR leads the UK Productivity Commission; gathering evidence on the scale of our country’s poor productivity performance and proposing policy solutions.

How does Scotland compare in terms of productivity with other regions?

In a recent report published by NIESR, we compare Scotland’s productivity performance with that of other EU and UK regions in the period 2009-2017. The UK and the global economy have witnessed an unprecedented slowdown in productivity growth following the financial crash of 2008-09. As much as in the rest of the UK, productivity growth in Scotland has remained weak ever since. Productivity is a key driver of real incomes and living standards, and finding solutions that can boost productivity should be top priority for most advanced economies.

Scotland is in the second highest quartile of the GDP per capita distribution in EU regions, ranking 41 out of all 104 EU regions. Our comparative analysis focuses on a group of benchmark regions that are at a similar level of economic development to that of Scotland. While productivity growth in Scotland has stagnated, these benchmark regions have excelled in terms of labour productivity growth, and have moved up in the productivity rankings. This group includes regions in Germany, Belgium and France.

What are Scotland’s strengths and weaknesses in terms of productivity?

We investigate the causes underlying the productivity gap between Scotland and a set of comparator regions during the period 2009-2017. Our research examines the role played by investment in physical capital, which includes infrastructure, machinery and computers, as well as Research & Development (R&D) spending and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). We also compare performance in terms of Total Factor Productivity (TFP), which is a measure of productive efficiency and can broadly be interpreted as a measure of technical efficiency and technological progress, although it can also include a number of other institutional, cultural and socio-economic factors.

Our report finds that Scotland has performed better than many UK regions in terms of investment, and that Scotland attracts a significant share of the UK’s foreign direct investment, only behind London and the South East, which are the leading areas of the UK. This investment fosters job creation and helps to generate future productivity gains. Scotland has a well-educated workforce, and the share of the population with tertiary education (just under fifty percent) is similar to that of leading regions in Europe.

However, compared to its UK and EU counterparts, Scotland has fared worse in terms of Total Factor Productivity and innovation. We highlight the relatively low R&D investment in Scotland’s business sector, with the lowest percentage of innovation-active businesses among UK nations, although this has improved in recent years. Innovation by public research institutions has been more promising. Our analysis suggests that an increase in R&D would lead to faster Total Factor Productivity growth in Scotland, and this relies on having a highly skilled workforce. But a greater role for graduates, and the reduced importance of intermediate qualifications can lead to skill demand and supply mismatches, and this has negative consequences for productivity. A reported lack of soft skills such as leadership skills could also be a drag on business productivity for Scotland.

What are the main policy implications and what does this means for the Levelling-Up agenda?

Looking at two pillars of the Levelling Up White Paper, our results suggest that skills R&D and innovation should be areas of priority in the path towards sustained and sustainable growth. Our work builds on evidence suggesting that firms that innovate become more productive. But crucially this is the case also for the least technologically advanced firms and lagging regions. Yet the bulk of R&D spending is largely concentrated in the South East and in higher-tech sectors, further widening longstanding regional inequalities.

Consistent with some of our previous work, we show that public R&D support is more effective in Scotland compared to other areas of the UK and fostering collaboration between private companies, universities and research institutes could be a way to boost innovation in a wider spectrum of firms.

In terms of skills, we find that having a well-educated workforce should enhance firms’ abilities to acquire external knowledge and learn from others, which is important to make more effective use of knowledge, ideas and technologies that are generated elsewhere. This is important for cases such as Scotland with a high presence of multinationals. But this should not be confined to skills acquired in the education system, in particular university education. On-the-job training, apprenticeships and soft skills should all be equally important for productivity.