A vague, much repackaged proposal of dubious practical use – the Immigration White paper is here at last

The Immigration White Paper is finally with us, like the awkward last minute Christmas present from a distant relative rewrapped several times to make it look more appealing. The Paper is supposed to address public concerns and give businesses and services clarity about how they will be able to recruit for the skills they need. But what’s beneath the not-too-pristine wrapping and is it what we need or indeed even what we say we want?

The Immigration White Paper is finally with us, like the awkward last minute Christmas present from a distant relative rewrapped several times to make it look more appealing. The Paper is supposed to address public concerns and give businesses and services clarity about how they will be able to recruit for the skills they need. But what’s beneath the not-too-pristine wrapping and is it what we need or indeed even what we say we want?

Theory has come before reality

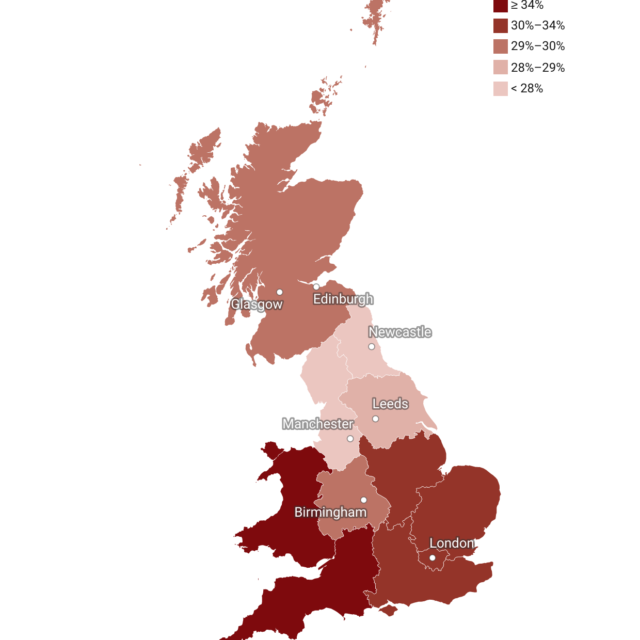

The White Paper makes a case for highly skilled migration to be prioritised to restrict ‘low-skilled’ migration. It proposes a threshold of £30,000 which will be put out to consultation. It backs up this policy by the findings of the report of the Migration Advisory Committee. Estimating the ‘average’ level of household income at which taxes exceed benefits at £30,000, the MAC argued that:

‘A more selective approach to EEA migration, which is not available under free movement, could provide an even more positive impact of migration on the public finances’

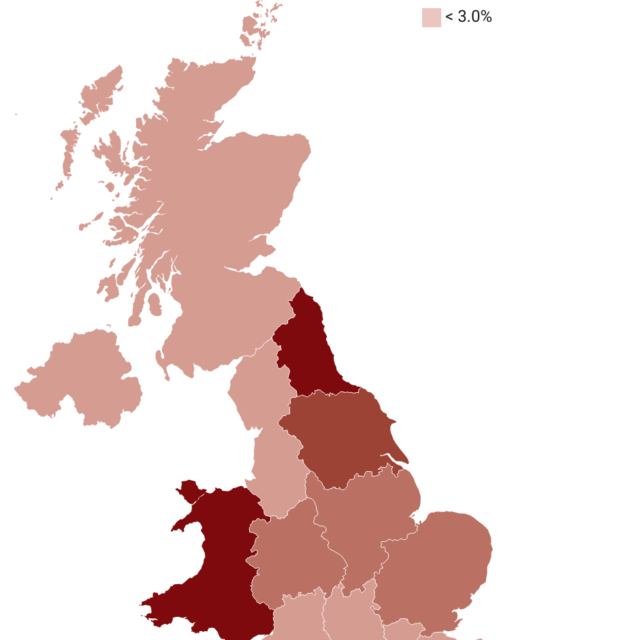

Sajid Javid argued that is someone is highly skilled ‘they should be earning more than £30.000’. But the fact is that many are not, especially outside of London and the South East. The White Paper suggests that the salary threshold could be reduced in some cases, but the fact is that many jobs carried out by migrants fall way beneath the threshold: in low paid but key sectors such as social care, tourism and transport they include many jobs at around the National Minimum Wage, not even £16,000 in many cases.

What about lower skilled migration?

The White Paper specifically rules out a route for low skilled workers but, in recognition of the ‘challenges’ faced by employers, it proposes 12 month visas, transferable between employers but with a ‘cooling off’ period to prevent consecutive contracts. It also announces a pilot scheme for the agricultural sector and proposes to extend current youth mobility schemes, as suggested by the MAC.

The White Paper suggests that employers might also draw on other migrants to meet low skill needs, for example dependants of skilled workers; students and refugees. But the only real proposals for lower skilled migration are for temporary visas, which employers consistently say would not meet their needs. Research by NIESR and the CIPD found that almost 9 in 10 employers surveyed said that one year visas would have a negative impact on their business. Short term visas which feature strongly in the Government’s proposals won’t meet employers’ needs for a stable and productive workforce. High staff turnover is costly and bad for productivity: even low skilled jobs include a period of training and familiarisation before a worker is fully productive. As NIESR research has found, many employers recruit migrants precisely because of high turnover among British workers in sectors such as social care. They want their employees them to develop skills, experience and company-specific knowledge, to progress to management positions. Employers also worry about policing short-term visas and the financial and reputational damage of unintended infringements.

Can’t employers just train more British workers?

In his Today Programme interview this morning the Home Secretary repeated the claim that employers recruit migrants rather than train up British workers:

‘Because of freedom of movement, it has been all too easy to bring in labour from abroad. (..)It is also right that we have a visa based system and it has rules around it so that there more is pressure on companies and employers to look to the domestic workforce first and to see whether they can upskill the domestic workforce….because immigration should never be a substitute for the investment that’s needed to improve the productivity of our country’

In fact, employers very largely do look to the domestic workforce first, research shows consistently that the most common reason for employing EU workers is that there are insufficient local applicants. This isn’t because employers are failing to train ‘home grown’ workers or using unfair recruitment practices. In fact, those who employ EU nationals are significantly more likely than employers without EU workers to have invested in training and have a diverse workforce, including by age and ethnicity. As the MAC report, on which the White Paper draws, clearly states:

‘Overall there is no evidence that migration has had a negative impact on the training of the UK-born workforce. Moreover, there is some evidence to suggest that skilled migrants have a positive impact on the quantity of training available to the UK-born workforce’.

The UK’s training system needs an overhaul, particularly in hard to recruit sectors such as social care and hospitality. Jobs need to be made more attractive, with clear career pathways linked to qualifications.

But any attempt to use future immigration policy as a means to force employers to invest more in training and skills is almost certainly bound to fail. These policy aims need to be achieved, but we shouldn’t pretend this can be done through a new immigration system

What would employers have liked to see in the White Paper?

Research carried out since the Brexit vote finds a consistent message about what employers would, and would not like from a new immigration system. CIPD and NIESR research finds strong support from employers for an immigration system giving preferential access based on national labour or skills-shortage occupations. But, unlike the White Paper’s proposals, this includes low skilled as well as higher skilled jobs. As our recent research for the Cavendish Coalition on the health and social care sector found, employers don’t mind having to offer a job before a migrant arrives or having to prove they haven’t been able to recruit, but the new proposals seem not to include these requirements.

Employers also want such a system to be simple, without the cost, bureaucracy and delays of the current Tier 2 visa system. NIESR research both before and after the referendum has found that the only thing feared by employers more than labour shortages is proliferation of red-tape when vacancies urgently need to be filled. The White Paper seems to be at least promising reduced red tape and fast visa processing times. But to meet the needs of employers and the economy the ‘straightforward’ and ‘light touch’ system it promises needs to apply to lower skilled labour and not just to the ‘brightest and best’ highly skilled individuals.

The proposals misjudge public concerns about immigration

Finally, will the White Paper’s proposals at least appeal to the public, as they are intended to do? Will they see the measures as exerting ‘control’ and addressing their concerns about immigration?

Our recent research in a Leave voting area of Kent found that the public does want more control over immigration through keeping out migrants of ‘low quality’. However, they didn’t see migrants who contribute through work and study as low quality, even those in low skilled and low paid work including agriculture, social care and warehouse work. The migrants the public are concerned about are those who are seen to come to claim benefits or to commit crime. And on this, attitudes are more influenced by perception than reality.

It would have been possible to enforce many of the restrictions that the public want within free movement, for example by having a formal registration system. It would also have been possible for politicians to be clear about the low rates of benefit claiming among migrants and to challenge the association between migration and crime. They chose not to because it suited them to be seen on the public’s side over immigration. We now have policy being made on the basis of perceptions, not facts, which will satisfy no-one and may leave us all worse off.