What Next for UK Industrial Policy and Productivity?

What’s the Chancellor’s plan for growth? Back in March 2021, Rishi Sunak published his ideas along with the budget and in the process scrapped the Industrial Strategy Council. Now that the White Paper on Levelling Up moves from publication to implementation, which policies should the government privilege to boost productivity and growth?

Our Deputy Director Professor Adrian Pabst spoke with Dr Konstantinos Myrodias, ESRC postdoctoral research associate at NIESR, who has recently contributed a chapter analysing these issues, as part of the latest occasional paper on Covid-19 and Productivity.

In his Mais Lecture, Chancellor Rishi Sunak pledged to limit state intervention in the economy after the pandemic. Does higher economic growth require a smaller role of the government in the economy?

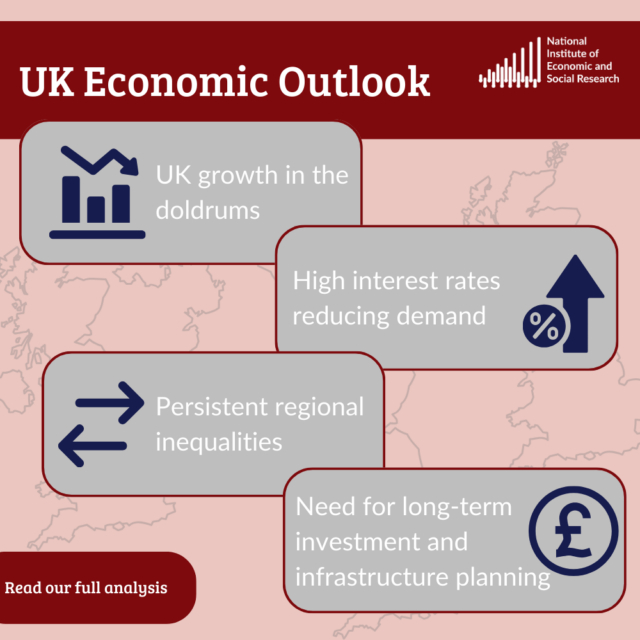

The question should not be the size of the state in the economy, but how effective government intervention is to boost economic growth. While growth at about 5 per cent this year is high, this is part of the bounce-backed after the Covid-19 shock but will not last. NIESR is projecting a growth rate of just one and a quarter per cent for the years 2023-26.

Moreover, the UK faces multi-level crises: the ongoing public health emergency (including NHS waiting lists and a lack of social care provision), Brexit’s economic challenges, together with chronic structural weaknesses, particularly the productivity slowdown, regional disparities, and income inequality. All these factors have put the brakes on economic growth. Market alone cannot reverse these trends and mitigate the effects of the recent crises on uneven development and the impact of climate degradation on living standards.

The government should identify inefficiencies in the economy and promote policies to ensure productivity growth and higher output. It should support sectors where capital markets refuse to finance on competitive terms and offer training to workers where needed to facilitate the re-allocation of resources to more productive sectors. Such an approach would bring positive externalities for innovation, the environment, and society. The question is not ‘how much state intervention is needed’ but rather ‘how effective government policies are’.

Does the UK have an effective growth policy in place?

For decades, successive British governments have invested limited resources in designing and pursuing growth strategies. The effort to put in place an industrial policy has gone in the right direction. However, the government’s current ‘Plan for Growth’ is based on a short-term and top-down approach that lacks a sufficiently strategic vision in order to succeed.

The government abolished the previous industrial strategy, citing at best vague criteria and giving no clear reasoning. In the 2021 ‘Plan for Growth’, decisions are taken in a highly centralised way that lacks cross-departmental consultation and co-ordination. The Treasury overshadows other ministries that maintain significantly less power. This concentration of power also leaves limited room for engagement with SMEs, regional authorities, and local communities. Spending decisions are highly centralised and funding allocation is often problematic, with towns having to spend precious resources on competing against one another in bidding for central investment. The British Business Bank still lacks more targeted financing.

Such a top-down approach together with policy discontinuities impede a functional policy to open the way for higher growth. If policymakers maintain a similar approach to the post-pandemic economic policymaking, then another decade of slow growth, stagnant productivity, and low living standards is around the corner.

What should be done?

The UK needs a new ‘bottom-up’ industrial policy with societal objectives such as quality jobs, the environment and wellbeing, which will be subject to regular evaluation independent of central government. Such a policy approach should be co-shaped in consultation with businesses, especially SMEs, regional authorities, and local communities, if it is to be effective and have long-term success.

Further devolution of powers is needed in both policy and spending decisions. Local councils need to have more decision-making powers and resources to pursue local growth policies.

A new approach should be taken to support business investment. The current capital investment by UK businesses remains very low at just 10% of GDP and far below the OECD average of 14%. A National Development Bank with a regional focus could accelerate access to finance and business investment. Financing should be linked to strict performance criteria, including exports and social impact, as well as ways to bring about regional regeneration.

In his Mais Lecture, Rishi Sunak pledged to prioritise ‘Capital, People, Ideas’ to boost growth. A fourth element should be added to his mantra: effective, joined-up policymaking that combines central funding and coordination with local design and delivery.