What is Really Happening with Inflation?

In the wake of the unexpectedly high CPI inflation release last Wednesday, our Deputy Director for Macroeconomic Modelling and Forecasting, Professor Stephen Millard, spoke to Paula Bejarano Carbo about inflation, core inflation and the monetary policy implications of the latest CPI release.

CPI inflation in April came in at 8.7 per cent, a fall of 1.4 percentage points relative to March. Why did it fall and why is it still high?

Annual consumer price index (CPI) inflation decreased from 10.1 per cent in March to 8.7 per cent in April. We’ve talked about what inflation is and how it is calculated in a previous Monday interview so I’ll take that as read.

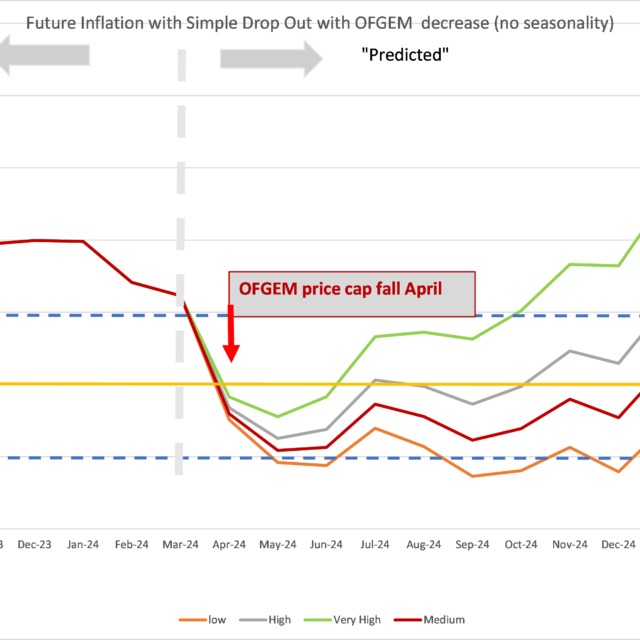

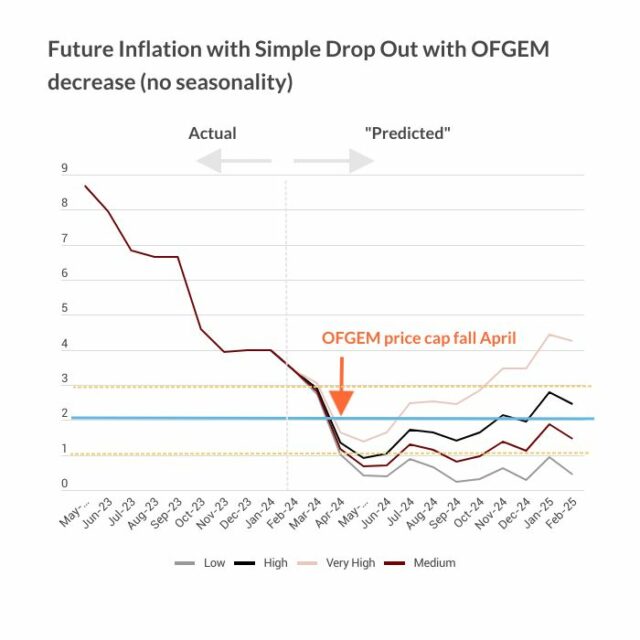

The latest fall in the inflation rate was driven by price decreases in housing and household services (specifically gas and electricity). We can think of this as last April’s energy increases ‘dropping out’ of the CPI basket. To elaborate, housing and household services inflation was 13.2 per cent in April 2022, but 12.3 per cent in April 2023. Since inflation is calculated on an annual basis, then the fact that this category saw a lower price increase in April this year relative to last year means that it contributed negatively to the overall April CPI inflation figure. Looking at an aggregate measure of energy (not just electricity and gas), gives us a better insight into the extent to which falling energy prices are affecting headline CPI. On aggregate, the rate of energy inflation fell to 10.7 per cent on the year in April 2023, down from a rate of 40.5 per cent on the year in March 2023. The magnitude of this monthly fall largely reflects energy price inflation in April 2022 of 52.2 per cent. So, energy prices falling can explain why CPI fell in April relative to March.

At the same time, other elements of the CPI basket increased relative to last April, contributing positively to April’s headline inflation figure and explaining why inflation still remains well above the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target. For instance, food inflation increased by 12.6 percentage points between April 2022 and April 2023. Between, March and April, the annual rate of food inflation fell by only 0.1 percentage points from the 45-year high of 19.1 per cent in March. It is notable that Food is weighted higher than energy in the CPI: Electricity, Gas and Other Fuels is weighted by 49/1000 whereas Food is weighted as 107/1000 currently.

Clearly, though falling energy prices are driving an overall fall in headline CPI inflation, this is being partially overtaken by a significant rise in food prices. Additionally, the rate of inflation of services and non-energy industrial goods has plateaued at around 7 per cent. It seems elevated inflation in April is a story of increasing food inflation and persistent inflation in other categories, like services, overtaking dropping energy prices.

Core inflation rose to 6.8 per cent, its highest since March 1992, while NIESR’s measure of trimmed-mean inflation topped 10 per cent. What are these measures and what do they tell us about inflation looking forward?

Core inflation and trimmed-mean inflation are two measures of underlying inflation. In other words, they capture some information about the nature of inflationary pressures in the economy. Core inflation is simply the ‘headline’ CPI level, excluding energy, food, alcoholic beverages, and tobacco as these are volatile items that tend to affect the overall inflation rate without necessarily affecting other prices in the economy. NIESR’s measure of underlying inflation is a measure of ‘trimmed-mean’ inflation, which excludes 5 per cent of the highest and lowest (most volatile) price changes.

A high rate of underlying (either core or trimmed-mean) inflation suggests that headline CPI inflation will exhibit persistence in 2023, i.e., fall more gradually than it otherwise would. It is useful to compare distinct measures of underlying inflation, as each gives us a different insight that can help inform our understanding of overall inflation dynamics.

Core inflation rose to 6.8 per cent in April, its highest since March 1992, from 6.2 per cent in March. It remains well above the series average of 2 per cent. This measure indicates that, as a result of the original inflation shock, inflationary pressures have permeated indirectly (sometimes referred to as ‘second-round inflation effects’) to other areas of the economy.

At the same time, NIESR’s measure of underlying inflation, which excludes 5 per cent of the highest and lowest price changes, rose to a new series high of 10.2 per cent in April from 9.9 per cent in March. Trimmed-mean inflation being higher than headline inflation indicates that the energy price fall which has driven headline CPI inflation down is a rather volatile price movement.

Overall, these figures suggest that we have yet to see a meaningful turning point in underlying inflationary pressure in the United Kingdom.

What does this all mean for interest rates?

On 11 May, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) opted to raise the Bank Rate by 25 basis points, bringing it to 4.50 per cent, to maintain the inflation rate at its 2 per cent target. While many thought May’s hike represented the end to the current monetary tightening cycle, last Wednesday’s figures suggest the MPC may have to tighten further.

To elaborate: with core inflation now at 6.8 per cent, alongside elevated wage growth, it is possible that high inflation may have become embedded. Indeed, over the past year, core CPI has fluctuated around 6 per cent, unsurprisingly mirroring the trend in services and non-energy industrial goods inflation. In a similar vein, the annual growth rate in the GDP deflator – which is a good measure of domestically-generated inflation – was 5.4 per cent in 2022. Broadly speaking, it is useful to think of these measures as picking up the inflation that the Monetary Policy Committee wants to, and can, return to the 2 per cent target through use of its conventional monetary instrument. That they are averaging 6 per cent, and still rising, is a concern in that it implies a possible need to tighten monetary policy by more than the MPC have already.