What Should the 2023 Spring Budget Contain?

This coming Wednesday, the Chancellor will present his Spring Budget for 2023. For our latest Monday Interview, our Deputy Director for Macroeconomic Modelling and Forecasting, Professor Stephen Millard looks forward to the Budget, tackling questions posed by our Director, Professor Jagjit Chadha, about the role of fiscal policy and the measures he would like to see announced.

What is the role of fiscal policy and to what extent does the current fiscal framework enable governments to achieve this?

The role of fiscal policy is fundamentally to improve the welfare of UK households. The government can do this by using taxes and subsidies to deal with market imperfections and externalities, redistributing from richer to poorer households, providing ‘public’ goods – that is those that would not be provided by the market – and ‘merit’ goods (those that society deems too important to leave to the market such as healthcare in the United Kingdom), and encouraging productivity growth across the whole of the United Kingdom via well-targeted investment in public infrastructure. Of course, it needs to do all of this while obeying its budget constraint, that is, not setting borrowing off on an unsustainable path.

Unfortunately, it is not at all clear that the current fiscal framework actually allows governments to do this. Under the current framework, the Chancellor sets himself targets for the public finances: currently, the two targets are to get borrowing below 3 per cent of GDP and underlying debt falling by fiscal year 2027-28. It is noticeable that these, essentially arbitrary, targets act as limits on the ability of the Chancellor to achieve the fiscal policy goals I outlined above; it is rare for the Chancellor to refer to these goals in his/her budget speech and even rarer for budgets to be independently evaluated against these goals. Instead, the independent Office for Budget Responsibility, OBR, simply evaluates whether or not the budget meets the numerical targets, conditional on their forecast for GDP and inflation.

NIESR has long argued that there is a need for a new fiscal framework, which enables the government to concentrate on the ultimate goals of fiscal policy, while ensuring long-run sustainability. In such a framework, the Chancellor would be required to follow a structured timetable for fiscal events and deliver more comprehensive Budget speeches (and not ‘test the waters’ by leaking policy announcements ahead of time). The OBR would publish pre-fiscal event reports and the Chancellor would produce economic risk assessment reports and these would ensure greater transparency and accountability, in particular, by making it clear how fiscal policy was working to improve the lives of UK households.

How much room does the Chancellor have to cut taxes and/or increase spending?

As I’ve tried to stress, I do not think that the fiscal targets should be seen as a useful guide as to what the Chancellor should or should not do on Wednesday. Back in November, the OBR assessed, in its Economic and Fiscal Outlook, that the Chancellor to be able to meet his new deficit-to-GDP target with £18.6 billion (0.6 per cent of GDP) to spare and his new debt-to-GDP target with £9.2 billion (0.3 per cent of GDP) to spare. Last month’s release of the Public Sector finances suggested that the government had an additional £30.6 billion to spend and that public debt was 98.9% of GDP, 1 percentage point lower than expected in November. Based on an assumption of unchanged government spending and a higher inflation rate than the OBR forecast in November, we calculated that the amount of fiscal space could be £166 billion more than the OBR’s November estimate. The point is not that we necessarily believe that this is the correct number; after all, forecasts tend to be wrong! Rather, it’s that small changes in assumptions can make a big difference to the fiscal targets and, hence, to fiscal policy itself. Again, we are back to the need for a new fiscal framework where policy is not set based on these arbitrary targets!

If policy is credible, then the government can always borrow. If policy is not credible, then the markets will increase the cost of government borrowing, as we saw in response to the mini budget last September. The key is to set policy ‘to do the right thing’ and to ensure that there is a credible plan for ensuring that borrowing does not explode.

What should the Chancellor do on Wednesday?

I believe the Chancellor does have room to cut taxes and/or increase spending in the budget on Wednesday. Given that, I would look for him to reduce the planned rise in corporation tax from 19 per cent to 25 per cent and/or soften the blow by increasing investment allowances; I would look for a large increase in public investment; I would look for an increase in public-sector pay; and I would adopt a combination of an opt-in Social Tariff system and a Variable Price Cap for household energy bills. Let me elaborate on each of these in turn.

A rise in corporate taxes leads to a fall in investment and GDP. But, worse than that, the fall in investment leads to a lower capital stock relative to its pre-tax-increase trend and this, in turn, leads to lower productivity and output over a longer time period. Investment subsidies – such as the super-deduction due to expire at the end of March – encourage investment and, so, raise long-run productivity and output. Given our woeful productivity performance since the Global Financial Crisis, a smaller – or even zero – rise in the corporation tax rate combined with an increase in investment allowances would seem a good example of a change in fiscal policy aimed at improving welfare. Related to this is the idea of an increase in public investment. Public sector net investment is set to fall from 2024 onwards with the OBR expecting it to reach 2.2 per cent of GDP by the fiscal year 2027-2028. NIESR have long argued that an increase in public-sector investment – especially in skills and infrastructure – is needed if we are to improve UK productivity. Wednesday’s budget provides the Chancellor with an opportunity to do this.

The recent strikes – not to mention labour shortages – in healthcare and education in particular strongly suggest that public-sector pay is too low. This has resulted from the large falls we’ve seen in public-sector real earnings over the past couple of years. In particular, the fall in real public sector earnings has been much larger than in the private sector. Unless public-sector pay starts to catch up with private-sector pay, we are likely to see further industrial unrest and, potentially, an exodus of staff from the public to the private sector. If this happens, the problems in our schools and hospitals will only get worse. Again, Wednesday’s budget provides the Chancellor with an opportunity to announce improvements in public-sector pay that could help avert this.

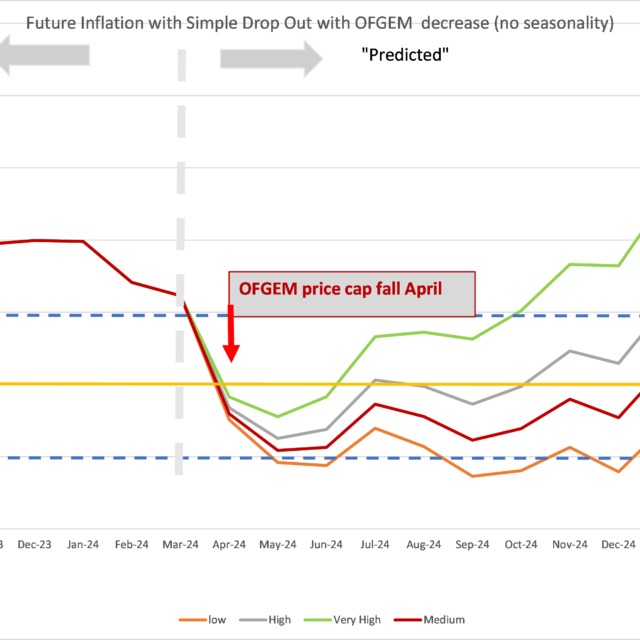

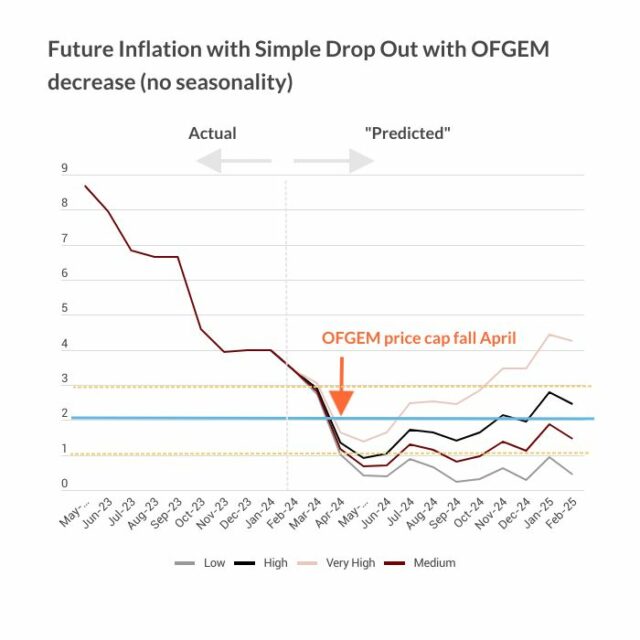

Finally, NIESR’s latest UK Economic Outlook showed that, while government support schemes have mostly offset the effect of inflation has been mostly offset for the poorest households by government, middle-income households have been left exposed to it. The energy price guarantee – while welcome – is ineffective in providing sufficient help for the bills for the poorest and unnecessarily expensive. So, instead, my colleagues have proposed an alternative combination of an opt-in Social Tariff system – which would discount energy for poor and vulnerable households based on the information they provide to their energy supplier – and a Variable Price Cap, which would raise the cost of energy with usage for all other households. They have calculated that a Social Tariff that aims to limit the bills for the poorest at 10 per cent of their incomes would cost £7bn per year, less than a quarter of the cost of the energy price guarantee for 2023. A Variable Price Cap could be cost neutral as the bills for lower-income households (who use the least energy) could be paid for by raising the bills in equal measure for the higher-income households (who use the most). Such a system would provide a more cost-effective way to reduce the energy bills for those who need it most while still incentivising lower energy demand.