Why is housing policy such a mess?

It is over forty years since Tony Crosland set up the Housing Finance Review in order to simplify housing policy and make it more coherent. A reasonable view of the current situation is that his initiative and many since have all failed in that objective.

It is over forty years since Tony Crosland set up the Housing Finance Review in order to simplify housing policy and make it more coherent. A reasonable view of the current situation is that his initiative and many since have all failed in that objective. Rather governments have built policy on policy, resulting in an accretion of initiatives which have consistently failed to provide ‘a decent home for every family at a price within their means’. The government’s latest attempt to provide a framework in its Green Paper ‘Fixing Our Broken Housing Market’ (DCLG, 2017) includes many good ideas about how we might slowly move towards a more effective approach. However, policy currently appears to be mired in a numbers game based on new build targets that bear little relation to reality; together with a continued emphasis on owner-occupation against a background of a precipitous fall in the proportion able to become owner-occupiers over the last fifteen years.

One of the biggest reasons for the ineffectiveness of housing policy is that it is unclear who is really in charge. Housing policy is technically the remit of the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. But any policy that involves taxation or subsidy needs at least the agreement of the Treasury – and indeed is often led by the Chancellor, as for example was the case with respect to Help to Buy first announced by George Osborne in the 2013 Budget. Equally any policy which involves lending or interest rates is part of the monetary policy remit of Bank of England – so access to mortgage finance is significantly determined by their views on overall financial stability with little respect for its impact on housing. Equally the Department of Work and Pensions plays a key role in housing affordability through the housing benefit system as well as by exercising significant control over rent setting in the social sector. Many other Departments also have a say. Given the range of interests and priorities involved it is hardly surprising that policy can seem (and is) incoherent and indeed inconsistent.

But perhaps the most important issue is that we expect far too much of housing policy. Rather, more general economic and social/cultural factors may actually be stronger than any policy initiative – so Ministers are often in the position of fire-fighting, as for instance after the financial crisis or simply being behind the curve when new pressures appear unexpectedly.

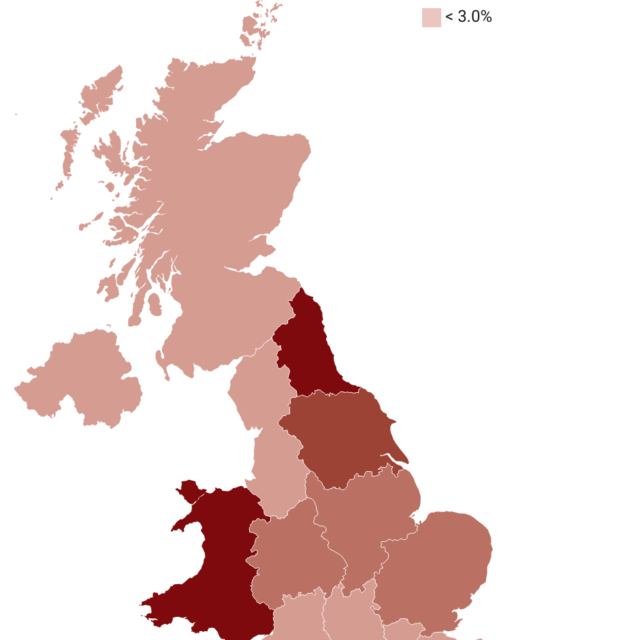

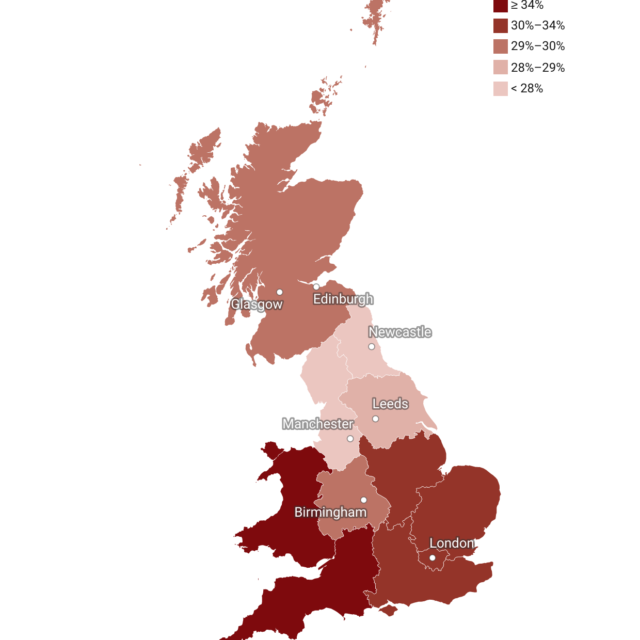

Just to take one example: the growth of the private rented sector. Between March 2003 and March 2017 more than 1.35m units were completed in the private sector – the vast majority for owner-occupation. Yet, over the same period, the total number of owner-occupied dwellings only increased by just over 300,000 a fall in the percentage of the total stock which was owner-occupied from 69% to 63%. In the social sector 330,000 units were built, but the stock declined by 110,000 (from 20% to 17%). Thus while new build was concentrated in the majority sectors – in line with policy – the dynamics of the market were actually that they were building for the private rented sector. Government hardly seemed to notice these trends and their implications, let alone predict them. And indeed until quite recently have put no policies in place to make the sector work more effectively.

Even so, one can argue that the growth of the private rented sector was at least to some extent the result of policy because it has been encouraged by the unintended consequences of other major policy initiatives undertaken to achieve quite different goals.

In particular:

- the Right to Buy has transferred almost 2 million dwellings into the owner-occupied sector since 1980. But maybe 40% of these dwellings, especially those located in poorer quality accessible areas, have been transferred into the private rented sector;

- policy initiated reductions in the availability of social rented housing have led to large numbers of lower income households becoming private tenants. This in turn has led to a massive increase in the housing benefit bill helping to support private rental investment;

- regulatory change, together with relative stagnation in incomes and insecure jobs among younger households has meant that many potential owner-occupiers are being excluded from the sector, even though they could well afford to buy. In this context the median first time buyer is paying around 17% of income in capital and interest payments. The equivalent figure for private tenants is well over 35%. This gap is indicative of the fact that many households are being excluded from entering owner-occupation and as a result are renting at much higher cost;

- the impact of the government’s quantitative easing policy, as in most other countries, has had a major effect on asset prices – which has in turn fed through into increased demand for rental housing because of the lack of alternative investment opportunities for many households; and

- perhaps most fundamentally, the Bank of England’s core role is to stabilise the overall financial system. If this means that housing suffers that is to a significant extent not something that they can worry about.

So maybe it is wrong to blame housing policy makers. It is not so much that they have an impossible job but rather that we simply have not got a grip on housing implications when setting all these other policies.

Christine Whitehead is Emeritus Professor of Housing Economics at the LSE. Her article, “Housing Policy and the Changing Tenure Mix” from our August Economic Review is available for free here. All views expressed are those of the author.