Global Growth Falters as Inflation Reaches its Peak

The slowing in the pace of global economic growth is forecast to continue this year, with growth of 2.5 per cent being the slowest (excepting the Covid-hit 2020) since 2009. The slowdown is most evident in advanced economies, some of which are likely to experience near-recession conditions.

Sign in to Access Pub. Date

Pub. Date

11 May, 2023

Pub. Type

Pub. Type

Main points

- The rapid increase in inflation in advanced economies following the price and supply shocks created by Russia’s war in Ukraine has directly affected consumer spending and consumer and business confidence. The very sharp tightening of monetary policy has exacerbated these effects.

- We have raised our global GDP growth forecast for this year slightly, to 2.5 per cent, but with recessionary conditions and risks still present. In the Winter Global Economic Outlook, we revised down our forecast for global GDP growth in 2023 to 2.3 per cent but with a somewhat stronger outlook for 2024 at 2.8 per cent. Since then, lower energy prices and slightly stronger readings for economic activity late last year and early this year, especially in China following the ending of lockdowns and in the United States, have resulted in a stronger than forecast start to this year. But worrying downside risks for activity, particularly in the United States and the Euro Area, remain. Outside the major advanced economies, the outlook is somewhat stronger but with continued uncertainty.

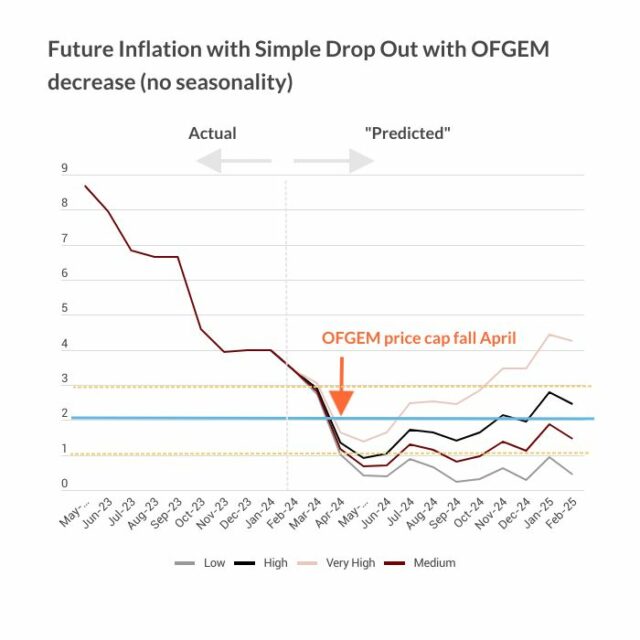

- The rapid increase in headline inflation in advanced economies has ended, aided by the reductions in commodity price inflation. But underlying or core inflation is proving to be persistent. We have reduced our global (OECD) inflation forecasts slightly - for 2023 from 8.5 per cent to 8.3 per cent and for 2024 from 5.8 per cent to 5.6 per cent. Inflation is expected to remain elevated relative to pre-Covid target rates in advanced economies in the next two years because price pressures have broadened beyond volatile items such as energy and food. However, lower energy and commodity prices and the effects of tighter monetary policies on demand will gradually feed through and lower inflation towards target in the medium term.

- The banking failures in the United States have acted as a reminder of the fragility of financial systems in a period of rapid monetary tightening and increased the downside risks to our baseline projection. Central banks will be mindful of such risks in their policy setting and are likely to take some comfort from falls in headline inflation as the year progresses. We now assume that the Federal Reserve (Fed) will increase policy interest rates by a further 0.25 percentage points and the European Central Bank (ECB) by 0.50 percentage points during the remainder of 2023. But, given that the pace of tightening we have already seen is contributing to the slow pace of economic growth, it is possible that interest rates may already have peaked.

- Given the uncertainties about the direction and duration of the war in Ukraine, energy and food prices, and the domestic responses to higher inflation across many countries, monetary policymakers are likely to look for a sustained fall in inflation before they consider reducing rates. Our market-based assumptions show advanced-economy central banks starting to reduce rates in early 2024, reflecting the stubbornness in underlying inflation. But there is a risk that policymakers, worried about the perception of their being too slow to loosen policy, just as they were seen as having been too slow to tighten in 2021, will be tempted to reduce rates earlier. Continued uncertainty over the war in Ukraine, food prices and financial stability mean that the economic outlook remains subject to downside risks. Our forecast and revisions since our Winter Global Economic Outlook are summarised in table 1.