A Risky Present

As we publish our Summer Economic Outlook, the UK economy may already be in recession and, with consumer price inflation close to double figures, the threat of stagflation has returned for the first time since the 1970s.

Pub. Date

Pub. Date

03 August, 2022

Pub. Type

Pub. Type

Key Points

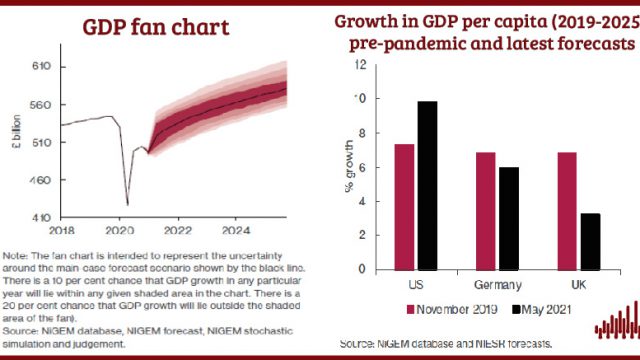

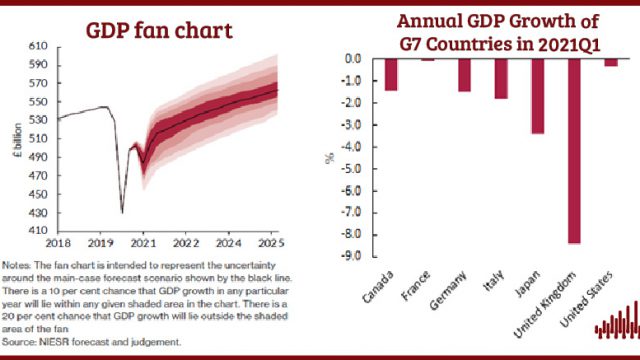

- The UK economy is likely to enter recession in the third quarter of 2022 and remain there until the first quarter of 2023. Our forecast for year-on-year GDP growth is 3.5 per cent in 2022 and 0.5 per cent in 2023. Unemployment is expected to rise above 5 per cent over the coming twelve months as firms respond to the fall in aggregate demand.

- CPI inflation is forecast to peak close to 11 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2022, returning to around 3 per cent a year later. This fall results from tighter monetary policy, a slowing in energy price inflation and falls in real incomes. The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee must continue to be cautious as it walks a fine line between tightening policy too quickly, worsening the recession, and too slowly, increasing the risk of high inflation becoming embedded in expectations.

- Earnings are expected to rise by 6 per cent in 2022 but we do not expect engrained domestic inflation to result from a wage-price spiral. With prices settling indefinitely at a higher level relative to incomes, real household incomes are forecast to fall by 2.5 per cent in 2022 and remain over 7 per cent below their pre-Covid trend beyond 2026.

- Three shocks have combined to shift real incomes onto a permanently lower path. Brexit has raised the cost of imports from continental Europe and incentivised households to switch towards more expensive domestically-produced goods and services. The recent rise in energy prices has constituted a large terms-of-trade shock for the UK. Finally, discretionary fiscal tightening over the 2021-24 period, following the shock of Covid-19, has reduced the resources available to the private sector.

- With government budgets set in cash terms, the government’s debt and deficits will be lower as a percentage of GDP, with the deficit forecast to fall to around 5 per cent in 2022-23 and 1 per cent in 2023-24. This means the government has more room to borrow to mitigate the effects of these three shocks, and we suggest some of this extra fiscal space is used to redistribute resources to the most financially vulnerable households (see Chapter 2).

- If overall government consumption is held fixed in nominal terms, either real public sector wages will fall significantly after a decade of very low growth, or services will be cut, or – as seems likely – both. We suggest that the government use some of its extra fiscal room to allow government employees’ wages to be set according to the requirements of individual sectors, rather than with an eye on inflation, to which they do not directly contribute.

- Finally, we would advise the government to focus on minimising the negative effects of Brexit by reducing the trade barriers between the UK and the European Union, including the Republic of Ireland. We would certainly advise against risking a trade war with our nearest and largest trading partner, the EU, by overturning the Northern Ireland Protocol, which has supported productivity and output growth in some sectors in Northern Ireland.

Dr Kemar Whyte gives a brief overview of the UK Economic Outlook:

You can watch our quarterly Economic Forum, where you can hear more about our UK and Global Economic Outlooks from the people who wrote them: