On the IMF’s Programs – Zambia and Sri Lanka Editions

Zambia and Sri Lanka need IMF programs—both have lost orderly access to foreign finance, classic IMF program territory. Zambia’s program has just begun, while that for Sri Lanka is imminent.

The IMF requires Zambia to Zambia to secure a fiscal primary surplus of 3.2 percent of GDP by 2026 and Sri Lanka a primary surplus of 2.3 percent of GDP by then. All other conditionality is derived from those two pivotal numbers, including the fiscal revenue and expenditure envelopes, the fiscal balance path from here to those terminal points, and all the steps required to get there. And those pivotal numbers are themselves derived from the target external debt service in each case.

However, those primary surplus targets are indefensible, and are the product of fundamental flaws in IMF priorities and corresponding work practices.

Best Peers

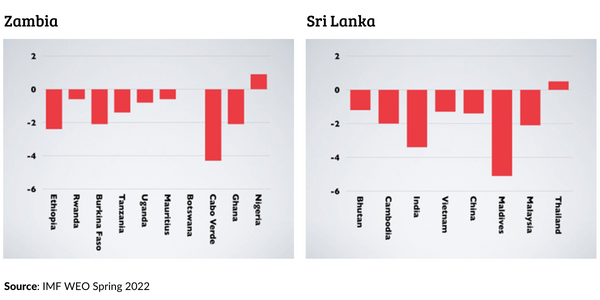

To see how and why, consider the following charts.

They show the average outturns for the primary balances for 2000-19—i.e., across several cycles, and undistorted by Covid—for a selection of the trend-fastest-real-PPP-GDP-per-capita growing macroeconomic peers of Zambia and Sri Lanka over that period—a balanced panel, with half the peers with higher PPP GDP/Capita, and half lower than Zambia and Sri Lanka respectively:

Fastest Trend Growth Peers, Average Fiscal Primary Balances, 2000-2019 (in Percent of GDP)

The average primary balance of Zambia’s fast trend growing peers is a deficit of 1.3 percent of GDP, and of Sri Lanka’s, a deficit of 2.0 percent of GDP.

So not one of their fast growing peers recorded an average surplus across cycles at the level that the IMF now insists is necessary for the medium term sustainability for Zambia and Sri Lanka.

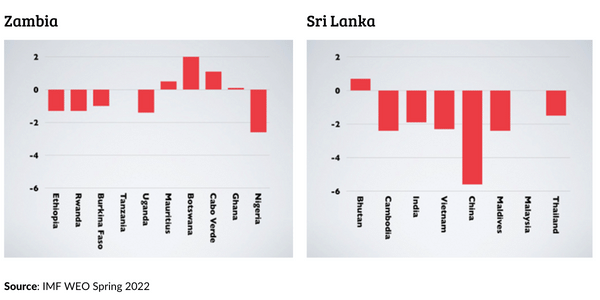

And as the following charts show, those target primary surpluses are also well adrift of what the IMF itself regards as appropriate for those same peers looking ahead to 2027—in the same global post-pandemic macro environment to which the IMF conditionality for Zambia and Sri Lanka applies:

Fastest Trend Growth Peers IMF Recommended Fiscal Primary Balances, 2027 (in Percent of GDP)

The average primary surplus the IMF recommends for Zambia’s fast growing peers for 2027 is a deficit of 0.3 percent of GDP, and for Sri Lanka’s high growing peers, a deficit of 1.5 percent of GDP.

And only one of their fast growing peers—Botswana, a precious minerals exporter—is recommended by the IMF to attain a primary fiscal surplus by 2027 anywhere near the levels it demands of Zambia and Sri Lanka.

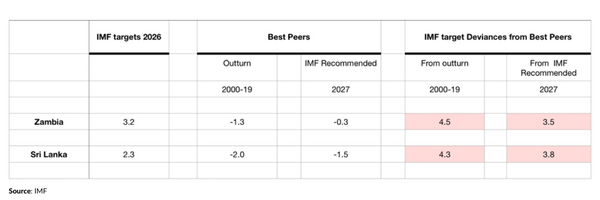

Thus, the IMF requirements for Zambia and Sri Lanka deviate substantially both from past best peer practice and from the IMF’s own assessment of best peer practice to 2027—of the order of 4 percentage points of GDP in both country cases.

The following table summarizes:

Fiscal Primary Balances (in Percent of GDP)

Thus, the concern is not with errors in multipliers but is with the terminal goals for 2026.

So why does the IMF insist on overall fiscal targets lacking a basis in the behavior of the best peers?

Not because

The answer cannot be “because of their excess public and external debts” because both programs include—indeed are largely motivated by—restructuring their debts. So a choice was made to limit debt restructuring rather than to accommodate macroeconomic peer best practice.

Nor can the answer be “because they are starting from disequilibria”. The point of IMF programs is to take countries back to sustainability. So the starting imbalances do not determine the sustainable end-point. Structural conditionality en route should also largely replicate the proven arrangements of best peers, rather than one-size-fits-all Econ 101 priors.

Nor can the answer be “to exceed the best”. In regard to the primary balance, that means combinations of raising taxes higher than necessary or/and cutting expenditures, including on necessary infrastructure, education, and the other investments in human capital. Such excessive zeal on the primary balance lowers potential output, as is manifestly evident in the data.

And nor can the answer be that “conditionality can be adjusted mid-stream.” The core case against the IMF demands is already evident. And such misspecification of conditionality at program outset itself imposes immediate undue burdens on fragile fiscal institutions and political balance. It thus runs counter to the overarching purpose of programs—stabilization.

Action

To correct all this, I proposed earlier that the Debt Sustainability Analyses (DSAs) which are routine in all IMF program staff reports should be subordinated to new Growth Sustainability Analyses (GSAs) rather than as now—implicitly given total absence of GSAs—vice versa.

In particular, those GSAs should constitute at each program outset precisely the balanced panel best peer group analysis that is outlined here for Zambia and Sri Lanka, supplemented by formal estimates of the level of GDP 5 years ahead that is lost to programmed deviations from such peer norms.

Any such deviations from those peer fiscal norms would have to be justified by IMF staff in those GSAs on grounds that the authorities were unwilling to adopt their best-peer policy practices, with each such key issue itemized, or reflecting some other exogenous special factor, such as the terms of trade, which significantly distinguishes the outlook from best peers.

And the aggregate and nature of debt restructuring and the quantum of program financing by the IMF would be calibrated from parameters derived from GSAs, not DSAs. Thus, programs would by default be oriented to sustain growth—the founding purpose of the IMF—rather than to sustain debt.

Zambia and Sri Lanka

In these two cases, absent explanations for deviations from best peers, the appropriate order of magnitude of the primary balance targets are those the IMF recommends for the peers.

That means balance for Zambia by 2026, not the IMF-required 3.2 percent of GDP surplus, and a deficit of 1½ percent of GDP for Sri Lanka, not the IMF-required 2.3 percent of GDP surplus.

Inaction

Sadly, the IMF has not taken this counsel, either on these balance target numbers for Zambia and Sri Lanka nor on the related broader proposal on its work priorities and practices.

Instead—as reflected in these primary surplus targets—it has chosen to prioritize debt repayment over growth, and it does not wish that to be obvious from its own routine program documentation.

And with this ongoing backstop globally assured, creditors—including Chinese—are willing to lend into unsustainable situations, which both diminishes the role of the Fund and delays policy correction.

All this underscores the importance of long-standing fundamental critiques of IMF governance.

Stop

Yes, It’s Mostly Fiscal.

But imposition by the IMF of outlier fiscal primary balance targets on such Sovereigns should stop.