CPI Inflation Holds Steady at 6.7 per cent in September and Set to Fall to 5 per cent in October

CPI Inflation was 6.7 per cent in September, unchanged from its August level. Month on month inflation for August-September 2023 came in at 0.5% per cent (which is an annualized rate of 6.3 per cent) whilst the old inflation from August-September 2022 of 0.5 per cent dropped out, resulting in no change in the headline rate. Inflationary pressures remain spread across most sectors and rates are well above the levels needed for the Bank of England to meet its target. The good news is that inflation will fall to about 5 per cent in October when the OfGEM price-cap increase of 2022 drops out.

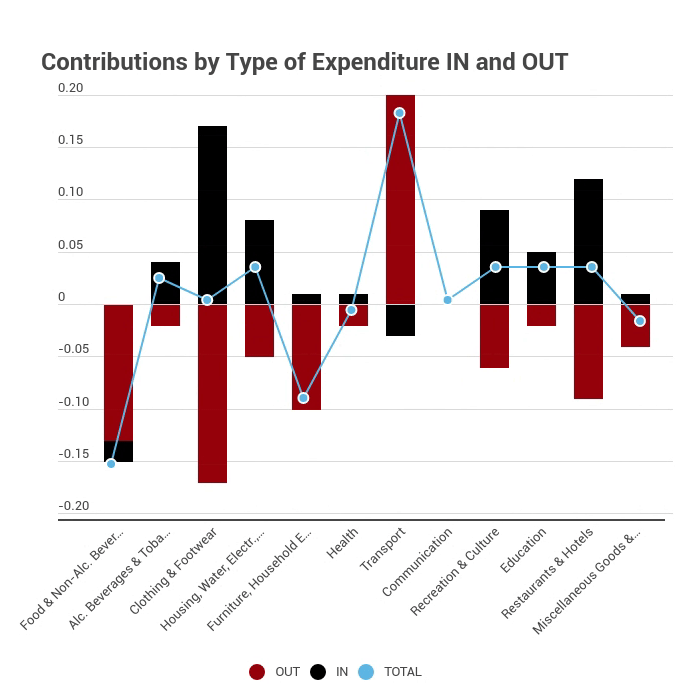

The big contributors to the change in inflation were:

Transport 0.17 percentage points

Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages -0.16 percentage points

Furniture and HH goods -0.10 percentage points

We can look in more detail at the contributions of the different sectors to overall inflation in Figure 2, with the old inflation dropping out of the annual figure (August-September 2022) shown in blue and the new monthly inflation dropping in (August-September 2023) shown in Brown, using the expenditure weights to calculate CPI. The overall effect is the sum of the two and is shown as the burgundy line.

We can see that across different types of expenditure there is a mixture of stories, but in most cases the dropouts and drop-ins are pulling in different directions, with the blue dropouts pulling inflation down and the brown drop-ins pulling it up. The two big exceptions are Transport where the brown drop-in is negative but the big blue drop-out dominates to give the big increase, and Food where both blue and brown are reducing inflation.

The fact that there are positive drop-ins across nine sectors and only negative ones in two sectors indicates that inflationary pressures continue to be widespread.

Looking Ahead

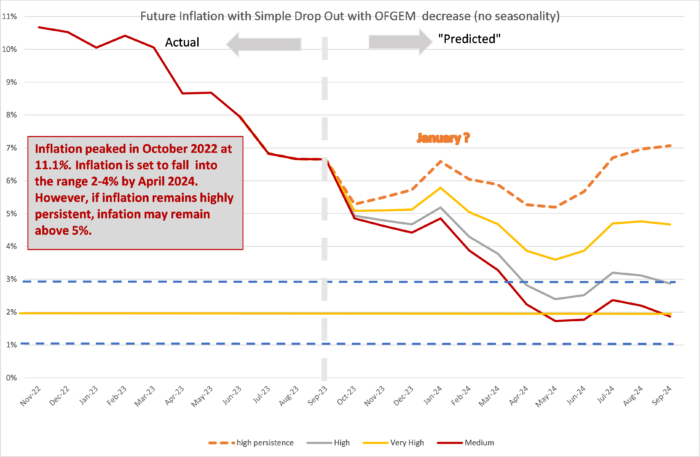

We can look ahead over the next 12 months to see how inflation might evolve as the recent inflation “drops out” as we move forward month by month. Each month, the new inflation enters the annual figure and the old inflation from the same month in the previous year “drops out”.[1] Previously we ended the “Sanctions scenario” introduced in March 2022 in response to the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. However, since the new month on month inflation became high again in Feb-May 2023, we have re-introduced the Sanctions scenario, but renamed it the “high persistence” scenario since the causes have little to do with war and sanctions but rather domestic wage-price dynamics. We depict the following scenarios for future inflation dropping in:

- The “medium” scenario assumes that the new inflation each month is equivalent to what would give us 2 per cent per annum or 0.17 per cent per calendar month (pcm) – which is both the Bank of England’s target and the long-run average for the last 25 years.

- The “high” scenario assumes that the new inflation each month is equivalent to 3 per cent per annum (0.25 per cent pcm).

- The “very high” scenario assumes that the new inflation each month is equivalent to 5 per cent per annum (0.4 per cent pcm). This reflects the inflationary experience of the United Kingdom in 1988-1992 (when mean monthly inflation was 0.45 per cent).

- The “high persistence” scenario assumes new month on month inflation of 0.6 per cent, which is equivalent to an annual rate of 7.4 per cent.

Our central forecast is the “very high scenario”. However, as inflationary pressures are persisting, we believe that inflation will be in the range between this and the “high persistence” scenario (most uncertainty seems to be on the upside). The high figures for wage growth published by the ONS on October 17th indicate that annual wage inflation (excluding bonuses) is still running at 7.8 per cent, which will put upwards pressure on service-sector inflation moving forwards and is likely to make aggregate inflation fall more slowly. However, when the “new inflation” starts to come down, we can shift our central scenario to the “high” and eventually the “medium” scenario. This may take some time, as discussed in When will UK inflation return to the Bank of England’s target of 2% a year? (Huw Dixon, Economics Observatory).

The main effect coming up is the huge drop out of inflation from October 2022: this was a 2% month on month figure, the largest such monthly increase for over three decades. This implies that October’s inflation figure will be the current level (6.7%) minus October 2022 (2.0%), plus the new monthly inflation for October 2023. If new inflation next month is 0.3% then the headline annual figure will be 5%; if new inflation is 0.5%, then the headline will be 5.2%; if new inflation is 0.1% the headline will be 4.8%.

The main uncertainty about future inflation is what happens in January 2024. January is a highly variable month due to the unpredictability of the January sales. In January 2023, there was a very large fall in inflation as the general price level fell (a rare event). When this drops out, there will be a very large positive effect on the headline January 2024 inflation figure. If the January 2024 sales are of the same magnitude as we saw in 2023, then there will be no change. However, if the January 2024 sales are smaller than the previous year, then headline inflation will rise. We have adjusted the “scenarios” to include a January 2024 sale effect of -0.3% which is more in line with the general seasonal effect. However, inflation is still likely to rise in January 2024, although the exact size is rather difficult to call. The size of this effect will influence all inflation rates going forward into 2024 and in that sense will be a key determinant of exactly when inflation will get to 2%.

The MPC meeting on November 2nd will be held knowing that inflation will drop significantly with the next ONS release on November 15th. It is therefore very unlikely that they will increase interest rates. However, I think they should not cut rates until after the actual inflation rate has declined to about 4%, which will probably not happen until February-April 2024.

This forecast assumes that geopolitical tensions do not deteriorate. Direct conflict between Russia and NATO would rapidly worsen the picture for inflation. Looking east, if the rising tensions between the United States and China lead to an intensification of the trade war or even open military conflict in the South China Sea or Republic of China (Taiwan), world supply chains would be disrupted, and inflation significantly raised, to levels far higher than seen in 2022. The current conflict in Israel-Palestine is unlikely to directly affect inflation unless it spreads out into a larger conflict involving Iran and affecting world oil and LNG supplies.

For further analysis of current and future prospects for inflation in the UK see:

How does Inflation affect the economy when interest rates are near zero? Economics Observatory.

How are rising energy prices affecting the UK economy? Economic Observatory.

[1] This analysis makes the approximation that the annual inflation rate equals the sum of the twelve month-on-month inflation rates. This approximation ignores “compounding” and is only valid when the inflation rates are low. In future releases I will add on the compounding effect to be more precise at the current high levels of inflation.