UK earnings growth likely to pick up further – and NIESR is on the case

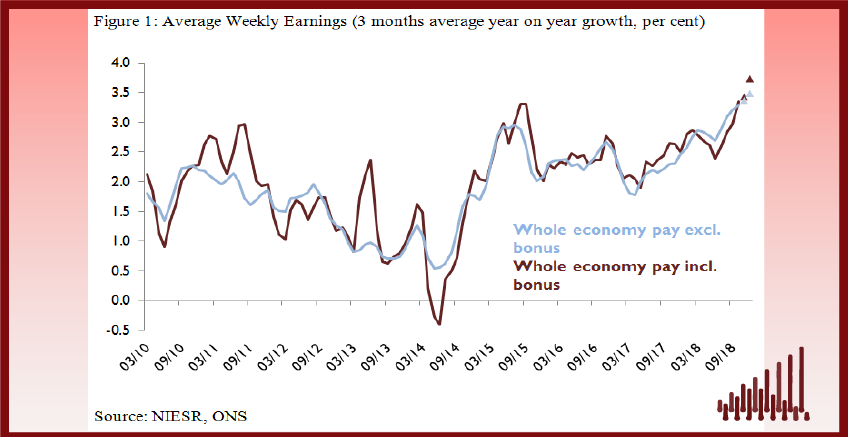

Earnings growth continues to surprise to the upside. According to new ONS statistics published earlier this week, UK average weekly earnings (AWE) expanded by 3.3 per cent (excl. bonus) and 3.4 per cent (incl. bonus) in the three months to October compared to the year before.

Building on the official data, we think that earnings growth still has room to pick up further. Our econometric models suggest that UK earnings will continue to accelerate going into the New Year.

Earnings growth continues to surprise to the upside. According to new ONS statistics published earlier this week, UK average weekly earnings (AWE) expanded by 3.3 per cent (excl. bonus) and 3.4 per cent (incl. bonus) in the three months to October compared to the year before.

Building on the official data, we think that earnings growth still has room to pick up further. Our econometric models suggest that UK earnings will continue to accelerate going into the New Year. According to our nowcasts, we see average weekly earnings growing by an average of 3.5 per cent in the final quarter of the year, consistent with rises of £1 or £2 per week over the last two months of the year (figure 1).

With the inflation rate currently at 2.4 per cent, and expected to fall moderately, real earnings are rising at a current rate of around 1 per cent for the first time in two years. The unemployment rate remains close to its lowest level since the 1970s. Although it looks like it is levelling off, we don’t think it is at a turning point yet.

While the headline unemployment rate stays low, employment in some sectors such as whole sale and retail trade services is falling. That is likely due to lower demand in that sector on the one hand, as well as a fall in labour supply on the other. As we discuss in another blog, net migration of EU migrants is now at its lowest level since 2012 amidst the Brexit turmoil. Higher wages there could be related to companies competing to attract scarcer workers in that sector.

After four years of private-sector outperformance, the differential between wage growth in the private and public sector recently seems to be closing. Public sector pay grew by its fastest rate in almost ten years in October at 2.7 per cent. Public sector wages were frozen for two years in 2010, except for those earning less than £21 000 a year, and since 2013, rises have been capped at 1 per cent. The scrapping of the cap on public-sector wage increases since the Spring Statement is a key reason for this growth.

In the coming months NIESR intends to produce and publish short-term predictions for average weekly earnings (regular pay and bonus payments) in the private and public sectors. The predictions shown in figure 1 and 2 are constructed exploiting information from key macroeconomic indicators. One of these is labour market trends. The relationship between wage growth and inflation is described by the wage-Phillips Curve: as unemployment declines, companies need to increase salaries to attract the scarcer labour. The models also build on information from monthly GDP nowcasts produced by NIESR’s GDP Tracker, and capture the interaction between private and public pay, shown to be relevant in work done by NIESR (Dolton et al. 2018). And finally, survey evidence is used, such as labour costs in the manufacturing and service sectors from the Bank of England Agents Score.

To check how our methodology would work in real time we produce judgement-free forecasts of earnings growth for the period between 2010M07 and 2018M10. For whole economy earnings, the root mean square error is 0.2% points for the measure excluding bonus and 0.4% points for the measure including bonus. So, on average, our projections can have an error of 0.2/0.4 percentage points above or below the forecasts we publish. These numbers are useful to understand the degree of uncertainty around the point forecasts produced by the models at each point in time. To note, the errors are greater for the measure of earnings including bonus and that is because bonus payments, particularly in the private sector, are subject to short-term volatility.