Regenerating the UK Regions

Regional regeneration is not simply a matter of central government spending. It raises fundamental questions of economic theory, in particular a body of research known as New Economic Geography.

The government’s main domestic priority of ‘levelling up’ those communities that have been ‘left behind’ by globalisation was not mentioned once during last Wednesday’s Spring Statement. Our Deputy Director Prof Adrian Pabst spoke with Prof Arnab Bhattacharjee, Professor of Economics at Heriot-Watt University and NIESR Research Lead on regional and household-level analysis about how New Economic Geography can provide answers to some of the questions around ‘levelling up’.

How does economic theory help us to think through ‘levelling up’?

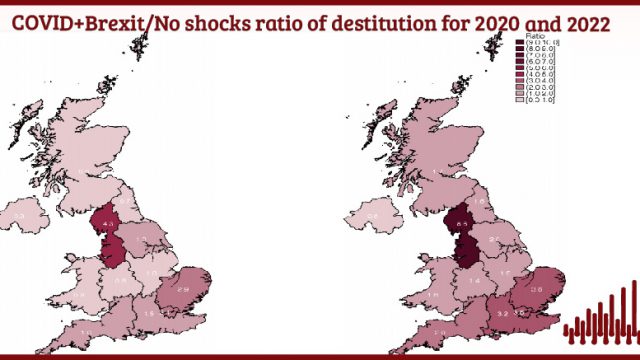

At a fine spatial scale, ‘levelling up’ can be seen either as realistic ambition or as a utopian goal. But in terms of current economic theory, the answer is more nuanced. Since the beginning of human civilisation, there has been economic agglomeration – the concentration of economic activity in certain places. These places were typically close to rivers which flooded every year and produced fertile land, but beyond that, the exact locations were based somewhat on historical accidents, or shocks as economists call them. Every centre of agglomeration is, by definition, surrounded by places of lower economic activity or dissociation sometimes in the hinterland and at other times further away. Hence regional disparities are a natural outcome of spatial economic processes.

One important point is the phenomenon of knowledge spill-overs which relate to flows of knowledge between people located in the same area. The idea is that local aggregation of firms belonging to related industries favour the exchange of knowledge between these firms, which in turn drive greater innovation and higher growth rates. In this sense, agglomeration and dissociation economies are pervasive.

Yet there is a tension, if not an outright contradiction: a standard economic assumption is that investment – in people or places – generates diminishing returns the larger the scale. This implies that once the optimal scale is reached, investors and entrepreneurs must find alternative places to invest in. Competition between these places will over time reduce spatial advantages and ultimately make all places equal. This is the theory behind the “levelling up” project, but it does not happen in practice. One can find alternative areas emerging, typically in the outskirts of large cities, and similarly inter-regional networks of productive places, but this does not make all places equal.

Given the persistence of regional disparities, what are the insights from economic geography?

Some 30 or 40 years ago, economic theory started to recognise that the potential for increasing returns to scale is necessary to explain the facts. This approach goes by the name of New Economic Geography. Paul Krugman was the sole recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2008 partly for his contributions to this line of thought. But several other scholars substantially contributed to this idea, in particular Masahisa Fujita and Tony Venables. Increasing returns of course means certain places can continue to grow and far outstretch others. In Britain, one can argue that London and certain parts of the South East constitute such a spatial cluster.

There is a complementary discourse in other areas as well, most notably the idea of social infrastructure and social capital, as emphasised by Robert Putnam, accumulating in certain places and communities and deficient in others. But neither New Economic Geography nor social geography deny the potential for alternative places to develop and grow, through accumulation of social infrastructure/capital or exploiting their own increasing returns. This is a source of great optimism.

How does this relate to contemporary Britain?

There are several critical issues here. First, the significant challenge lies in substantially larger spatial inequality in Britain, as compared with other developed countries. This is evident in productivity, but also most economic measures including standards of living. However, principles of fairness and equal opportunity mean that, despite this divergence, no one wherever they live should suffer from a lack of common basic necessities, like food, health and housing. In the absence of adequate local resources, this requires substantial fiscal transfers from more productive places at the core to less productive ones in the periphery.

Second, how much inequality is socially or politically admissible, or even optimal given agglomeration benefits? A judgement on this critical question requires adequate debate and discussion in society. Here it is important to recognise that, while transfers can improve material conditions, this does not necessarily translate into life satisfaction, agency or self-confidence. All these require improvements in social capital and social infrastructure.

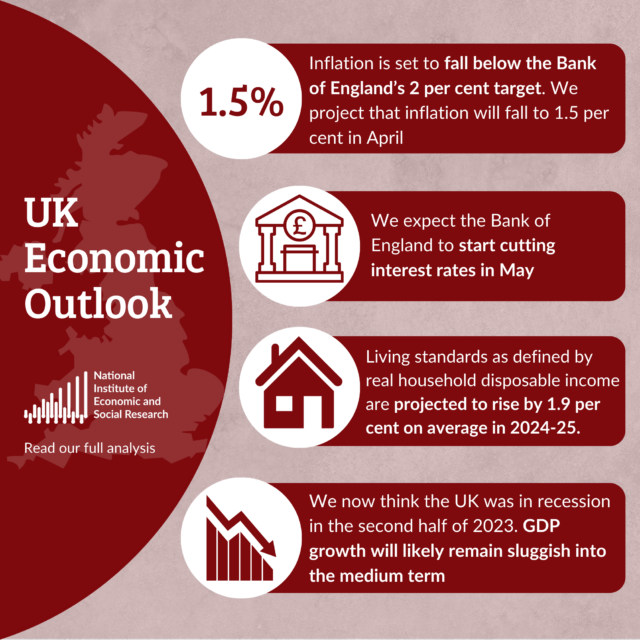

Third, productivity differences across the country are perhaps the most important factor. Productivity across the UK has been stagnating, with only London and parts of the South East achieving productivity levels comparable to other G7 economies. How can productivity be ‘levelled up’? As theory and experience tells us, this rarely if ever happens by chance – it requires investments in people and places. In an economic system, all places and peoples are connected to each other, which creates externalities that can be both positive or negative.

Therefore, investments must be based on the right choice of places in the periphery, and sectors or segments therein, that will generate a positive influence on the core at the same time as the core creates positive externalities on the periphery. Theory and evidence from other countries, as well as our own history, shows that this can be achieved through careful planning.

In light of this, are the plans in the White Paper on ‘Levelling Up’ adequate?

Work by the UK2070 Commission and other research shows that the enormity of the task to reduce regional disparities requires a 50-year time horizon with substantial investment and much careful planning. The first challenge relates to the public finances, which are currently struggling with the recovery from the Covid-19 shock. The second is an even greater challenge, because regional planning has been largely ignored in the country for a long time, so this would require a major policy reset. Third, the prospect for regional regeneration is closely bound up with questions of devolution and constitutional reform, which are huge tasks, too.

In the event, the White Paper does provide an excellent summary of regional inequalities and a long list of policy measures that can help address this. This is a big step forward in the political debate and in public policy. However, it also lacks crucial detail – how much spending and investments in which sectors and places? What are the likely outcomes? Within what time frame beyond 2030?

All of this requires careful evidence as well as by political and social debate, to generate buy-in from successive generations of citizens and governments. Hence, this is only the start of a process – and a lot needs to be done. But it can be done, and it needs to be done.