Rising Mortgage Costs. What Can Be Done?

Last Wednesday, the average interest rate on mortgage hit 6.7 per cent, up from around 2.5 per cent in 2021. Overall, millions of households could face significant cash-flow problems in the short term as fast-rising mortgage repayments add to higher energy and food costs. Our Deputy Director Professor Adrian Pabst spoke with Max Mosley, an economist in the Public Policy Team, about what this rise means for households and what could be done.

What impact does the rise in interest rates mean for people with mortgages?

A typical household that took out a mortgage in 2020 during the stamp-duty holiday would have been paying around 2.5 per cent of interest on their monthly repayments on average. That same household, three years later, will be looking to re-mortgage, as their three or five-year fixed rate deal comes to an end.

The economic environment today, however, is very different. Following the Bank of England raising interest rates at their fastest pace since Bank gained independence, those households will now have to absorb an interest payment of nearly 7 per cent. That 4.5 percentage point rise, for a typical household, would take their repayments from £600 to £900 overnight, which is a 50 per cent rise.

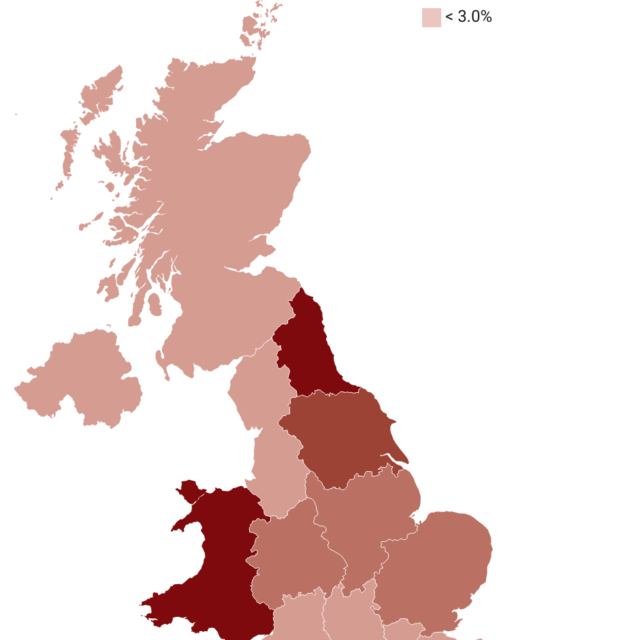

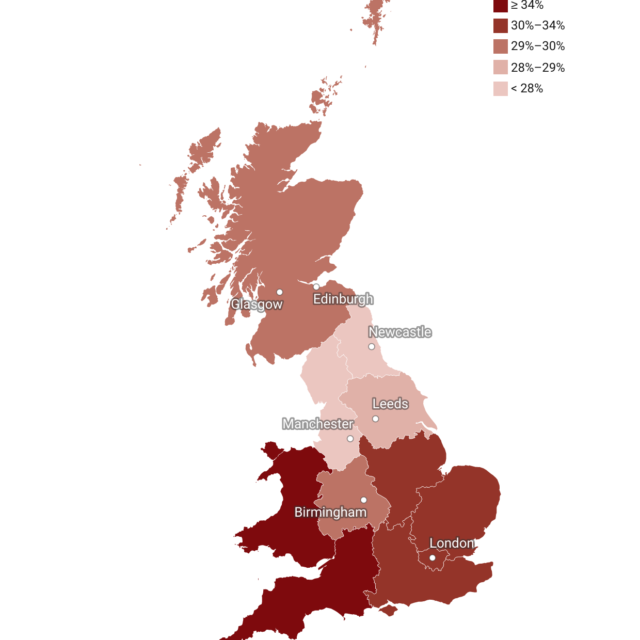

We have previously projected that 1.2 million households would see their savings wiped out as a consequence of higher mortgage repayments added to higher energy and food costs, meaning they would likely be unable to afford their monthly repayments and become cash-flow insolvent. The question is how many households can afford to go deeper into debt in order to avoid home repossession.

What can we do about this?

Although some argue that borrowers took out mortgages at their own risk, there is a strong argument that the current conditions are exceptional. This is for the simple reason that when someone applies for a mortgage, they prove their ability to afford the loan by showing how they can cope with a 3 percentage point rise in their monthly interest rates. Given these have risen beyond that level – and the fact we are in the midst of a once-in-a-generation cost-of-living crisis – it is reasonable to argue that not all households can be expected to withstand these pressures.

There are schemes in place to allow borrowers to adjust their repayments when under stress. In particular, forbearance agreements are the most effective tools, as they allow for the borrower to agree a temporary repayment plan and, crucially, does not affect people’s credit scores. The government should encourage this process, and potentially provide liquidity as and when necessary to facilitate this support.

How long would support need to last?

The good news is that the medium-term future looks bright for mortgage holders. Why? Because when inflation is high, wages rise too as workers ask for a greater salary to compensate for higher prices. Given the amount a household can borrow in terms of mortgages is fixed, the overall value therefore falls as wages rise. Put another way, the value of mortgage debt falls in real terms when inflation is high. Here it is worth re-reading Professor Huw Dixon’s description of how this works in our recent blog.

So in the long-run, inflation actually helps mortgage holders. The question for policy-makers is how to minimise the pain in the short term to see them over this difficult period. In reality, this is a significant cash-flow problem for many. So a forbearance arrangement really only needs to last for the period where inflation and the Bank rate remain elevated.