Are Price Controls on Food a Viable Option?

With core inflation persistent and food price inflation rising, is there a case for price controls? Or are there better policy alternatives? Our Deputy Director for Public Policy Prof Adrian Pabst spoke with Prof Arnab Bhattacharjee, NIESR’s Research Lead for Regional and Household Analysis.

Post Date

Post Date

Reading Time

Reading Time

What has been the impact of the cost-of-living crisis on UK households?

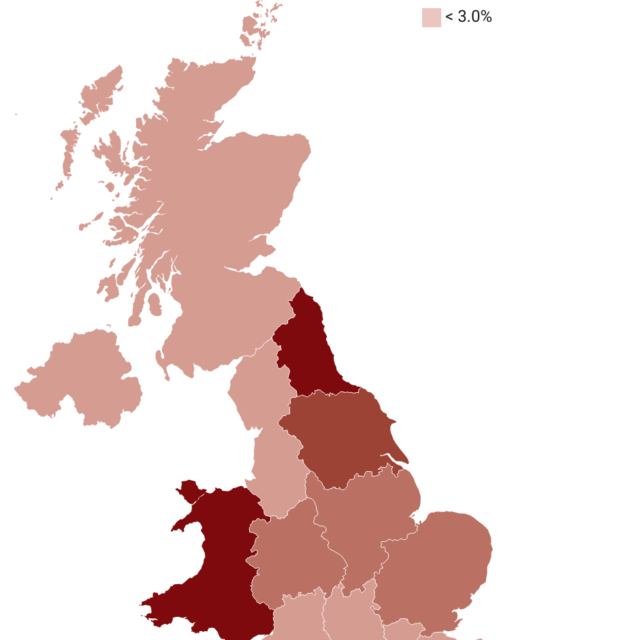

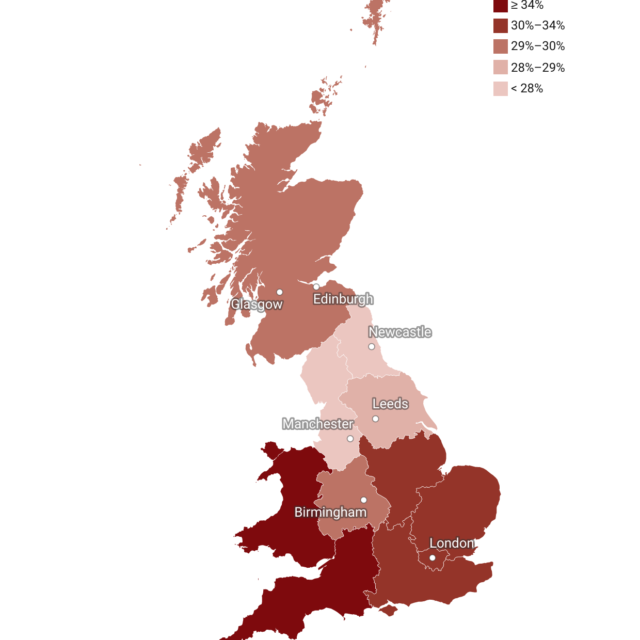

The cost-of-living crisis has brought about enormous hardship upon millions of households in the bottom half of the income distribution. The highest inflation was experienced in energy prices but they have recently started to stabilise and fall back towards pre-war levels. However, adverse effects continue to have ramifications as inflation in food prices continues to remain high and housing costs are rising. This is evidenced in persistently high core inflation which measures inflation in goods and services other than energy and food.

The greater issue is that high inflation does not affect all households equally. Some households are better able to bear the costs, either through proportionate increases in wages or business profits, or by dipping into savings accumulated during the pandemic lockdowns. But it brings disproportionate hardship for poor households and those with sluggish wages and negligible or no savings.

At the same time, as monetary policy continues its robust attempts to tackle inflation by interest rate rises, some of these suffering households are also left credit constrained. Either they do not have sufficient wealth to use as collateral and take borrowings against these, or they find the higher borrowing costs or access to financial markets limiting. The question is: should the government step in and control prices, particularly by setting price limits on food items?

Is there a case for price controls, specifically food prices?

Price controls, particularly direct ones that set binding price floors or ceilings, are an emotive and politically sensitive question. From an economic point of view, if the high prices arise largely from the demand side of the economy, it is unlikely and often undesirable that the government step in with direct controls. However, it can, and arguably should, step in with income support for specific households that struggle to get by. Some measures in this direction have been taken by the government starting with the Universal Credit uplift at the start of the pandemic and the Cost of Living payments since the 2022 Autumn Statement.

“It is much better to think about the households who are really having difficulty meeting their food & energy bills, & targeting support to them … rather than distorting the price mechanism”. @jagjit_chadha talking to @gurpreetnarwan from @SkyNews about food price caps. pic.twitter.com/PLat8jh4di

— National Institute of Economic and Social Research (@NIESRorg) May 31, 2023

On the other hand, price rises can also equally emanate from the supply side and particularly due to supply chain constraints. If these supply chain issues are thought to be temporary and short-term, then a positive argument can be made in favour of price controls or quantity rationing. In fact, this is precisely the context against which price controls and rationing were introduced, temporarily, in many countries, including Britain, in the years following the Second World War.

Most importantly, the government needs to think through carefully what implications such price controls may have, and on whom? Principles of fairness and facilitation of well-functioning markets would, then, also necessitate potential targeted fiscal policy interventions. This requires an assessment of the fiscal space available to the government and a clear sense as to responsible fiscal policy aimed to provide temporary and targeted support.

Are these conditions met?

A large part of food price inflation, as well as energy, certainly arose from supply chain disruptions. However, are these temporary and short-term? This is where there is a lot of uncertainty. One can make the argument that supply disruptions are temporary and ultimately the “invisible hand” of the market will take over. But then, two further questions arise. First, how short-term are the supply chain disruptions in the current context of de-globalisation? This is uncertain and, specifically for the UK, contingent upon the pace of post-Brexit trade relations with the EU and other parts of the world. Second, who is potentially affected adversely by the price controls? To start with, producers and retailers. Hence, in the absence of appropriate support, it may affect incentives and participation in the market. Together, it may also affect the ability of the market itself to get back to equilibrium prices or find a suitable new post-Brexit equilibrium. These are issues that, in our view, may not have been considered sufficiently enough to enable a strong case for price controls.

What else can the government do?

Potentially, we can learn some lessons from experiences worldwide. It is largely believed that price controls and rationing introduced after the Second World War were proportionate and useful, for example in North America and the UK. This was because supply chain disruptions were indeed transitory, and it was largely consumers (households) who bore the brunt – not the producers and distributors. Together, the controls introduced were promptly withdrawn when supply chain conditions improved allowing markets to function relatively independently. However, the experiences elsewhere were mixed, particularly in the Global South. In India, for example, the system of controls remained in place much longer. It can perhaps be argued that recent discord with agricultural procurement prices were a legacy of that period. This is sub-optimal.

In several countries of continental Europe, there are price controls on food and energy as well as other utilities. For energy and utilities, this partly takes the form of limits to price changes, together with regulation to ensure compliance. We have the same in the UK, particularly with energy price caps and differential VAT. The main difference lies in the intensity in the application of the limits. Arguably this allows utility service providers more leverage but there is a question as to whether the surplus so generated is distributed equitable between consumers and producers. This is a political issue on which more research and thinking is necessary.

In continental Europe, there are also agricultural price controls as part of the Common Agricultural Policy in the European Union. However, a prominent view (not least from the European Central Bank) is that “these regulations mainly have an influence on food products at an intermediate stage and therefore their impact on consumer prices is very difficult to identify”. In other words, it is not clear how effective these controls are.

In summary, it may be best for the government to provide targeted income support rather than trying to play the role of manipulating the price formation functions of the market. If it wished to set price controls at all, a clear sense is required as to how long these measures are intended and how affected participants (for example, potentially farmers, producers and retailers) will be compensated. In either case, fiscal decisions must be underpinned by a clear independent assessment by the OBR and disclosure of the impact upon government finances.

See our more of our work on the cost-of-living crisis here.