Integration isn’t about ‘improving’ minorities but preparing all children for life in diverse Britain

Today NIESR has published a literature review on promoting integration in schools. Commissioned by the Department for education to look at ethnic and religious integration, the review finds examples of good practice in bringing young people from different ethnic and religious backgrounds together, for example school linking and admissions policies aimed at reducing segregation.

Today NIESR has published a literature review on promoting integration in schools. Commissioned by the Department for education to look at ethnic and religious integration, the review finds examples of good practice in bringing young people from different ethnic and religious backgrounds together, for example school linking and admissions policies aimed at reducing segregation.

The review also highlights some problems with the term ‘integration’ when used in the context of settled communities. The tendency to place all ethnic and religious minorities in the same box, along with recent migrants, ignores their very different needs. And the view that integration is a means of raising standards and aspirations of ethnic minorities clashes with evidence of higher attainment levels among some ethnic groups and pupils with English as an Additional Language.

Schools are natural places for integration, but segregation is increasing

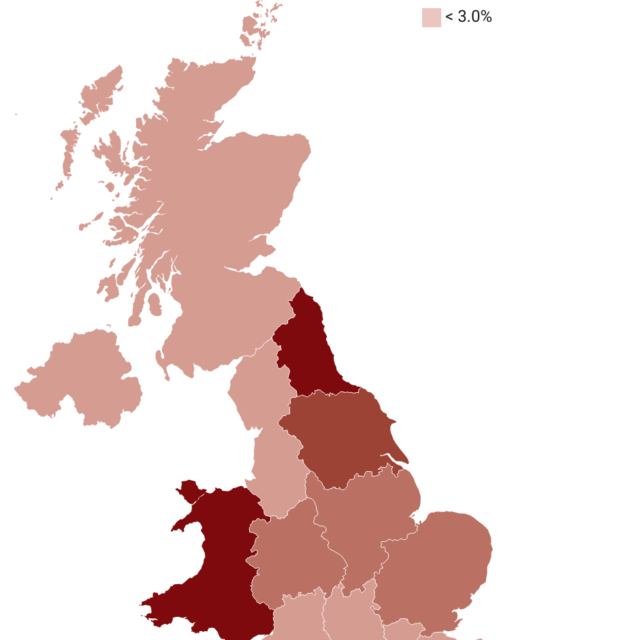

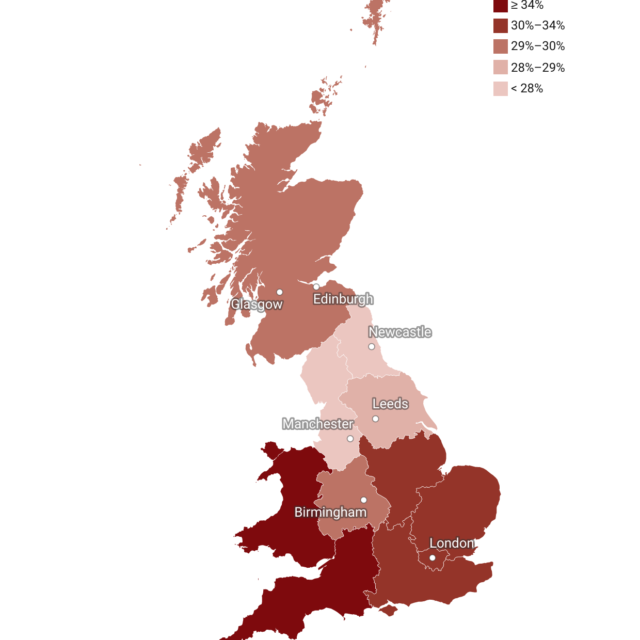

Commissioned in the light of the Casey Review (2016) and Integrated Communities Strategy Green Paper (2018) our literature review was intended to expand the evidence base on how to reduce segregation and improve relations between different ethnic and religious groups. The fact that schools are more segregated than the local communities in which they are situated continues to raise important policy questions. In fact the levels of segregation are getting worse rather than better, with the authors of the report ‘Understanding School Segregation in England’ finding an increase in segregation by ethnicity from 2011 to 2016. This is troubling because, as the authors conclude, mixed school intakes not only influence pupils, but have a wider impact:

‘Children form friendships, go to each other’s home and attend out of school events together on an ongoing basis. Moreover, parents also meet at the school gate and through school-based activities and therefore are drawn into the friendship networks of the child’

Integration is a flawed term which lumps diverse groups together

Our in-depth look at the literature found assumptions and confusion about who needs to be integrated, why and how. The term ‘integration’ makes sense in relation to new migrants whose needs often, but not always, include English language learning and familiarisation with a new system. The concept of integration is more problematic when applied to pupils from settled communities.

All ethnic and religious minority pupils will not share the same needs, yet the literature so often assumes they do. Some may need initial support with English, if it is not spoken at home, or their parents may need familiarising with the UK system if not brought up here. However, in many cases the families of ethnic and religious minority pupils have lived, worked and socialised in their local area for years, often generations. They need to have a school curriculum which meets their needs, to which they can relate, to have access to quality teaching from teachers with high expectations for all pupils. They also need to be protected from bullying and discrimination, which persists despite schools’ duties to take firm action.

All pupils need to be prepared for diverse Britain, yet the Government’s integration agenda has focused on issues which have little to do with social mixing. Its focus on radicalisation and pursuit of the ‘Prevent’ strategy could be argued to have harmed, rather than assisted integration. The Casey review even acknowledged ‘the absence of any work on integration on a similar scale’.

Admissions policies are key to integration

Our research found schools with diverse intakes which include recent migrants and settled ethnic minority communities integrate pupils very well in ways that benefit all pupils and their families. However, migrant pupils and those from ethnic minorities are by no means distributed evenly across schools. The real problem is that many schools are just not diverse enough.

Analysis by Professor Simon Burgess in 2015 found ethnic minority pupils are much more likely than others to go to schools where they are in the majority. And segregation between schools is increasing – intakes are becoming less diverse and fail to reflect the composition of their local area.

Pupils don’t end up in schools by accident and segregation is a result of parental choice and admissions policies – not just residential patterns. Studies by leading education experts highlight the lack of transparency in schools’ admissions practices. Faith schools contribute to segregation, by along religious lines by definition, but also increase ethnic segregation in nearby schools.

Studies by leading education experts highlight the lack of transparency in schools’ admissions practices. This has particular implications for social class segregation, but also leads to under-representation of ethnic minorities in some schools.

Parental choice is another key factor in school segregation. Last week the BBC reported research findings that more than 60% of parents opt for a school other than their nearest, usually because it is higher achieving. This practice was found more, not less, prevalent among parents of Black and Asian children but that they were also less likely to get their first preference.

The role of schools and parents in perpetuating segregation by social class and ethnicity strongly suggests the need for greater control and inspection of schools’ admissions policies and practices. As a step in the this direction, education experts have called for admissions to be taken out of schools’ hands and the Sutton Trust has proposed random ballots and banding.

The integration areas set up by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) have, not surprisingly, identified parental choice and admissions policies as key issues affecting segregation. Just how able they will be to bring about change, given the control by academies and free schools over their admissions, remains to be seen.

It’s time for less talk and more action on integration

Segregation in our school system isn’t problematic because it deprives ethnic minorities from contact with their white counterparts. It is a lost opportunity to prepare all children for life in a diverse society. It is a consequence of a flawed system which celebrates parental choice, but in fact perpetuates deep-rooted advantage and inequality of access. And it will not improve without targeted and concerted action by government and local admissions authorities.