It’s time to re-think welfare reform

The period from 2010 to the present has been one of far-reaching change in the design and delivery of welfare and of welfare to work. This has included the replacement of six key benefits with Universal Credit (UC); the introduction of an intensified conditionality and the sanctioning regime, requiring claimants to meet certain conditions or face losing benefits; and changes to assessment and entitlement to incapacity and disability-related benefits.

NIESR research for the Equality and Human Rights Commission, published today, reviews evidence for the impact of the reforms on protected, equality groups. Covering more than 400 sources of research evidence, we found that some reforms, for example UC, have winners and losers. Others have no winners, for example the benefit cap, bedroom tax and sanctioning. The data also clearly showed that the most disadvantaged in British society have been hit hardest.

The period from 2010 to the present has been one of far-reaching change in the design and delivery of welfare and of welfare to work. This has included the replacement of six key benefits with Universal Credit (UC); the introduction of an intensified conditionality and the sanctioning regime, requiring claimants to meet certain conditions or face losing benefits; and changes to assessment and entitlement to incapacity and disability-related benefits.

NIESR research for the Equality and Human Rights Commission, published today, reviews evidence for the impact of the reforms on protected, equality groups. Covering more than 400 sources of research evidence, we found that some reforms, for example UC, have winners and losers. Others have no winners, for example the benefit cap, bedroom tax and sanctioning. The data also clearly showed that the most disadvantaged in British society have been hit hardest.

What drove the reforms?

The reforms were backed by a clear strategy aimed at incentivising paid work over inequality and reducing welfare expenditure. The programme emphasised individual rather than structural barriers to work, such as local labour market characteristics, and brought the capacity of disabled people into view. The emphasis on individual responsibility was seen to drive increased conditionality around benefits and the use of sanctions. A second driver was the perceived unaffordability of the welfare system. It was seen as needing to be reduced in size and refocused on people who need and deserve it. As the then Chancellor George Osborne asked the 2012 Conservative Party Conference:

‘Where is the fairness, we ask, for the shift-worker, leaving home in the dark hours of the early morning, who looks up at the closed blinds of their next-door neighbour sleeping off a life on benefits’

Imagery of idleness and the narrative of ‘strivers vs skivers’ became the language of the welfare debate. This was despite the fact that unemployment benefits account for a small proportion of welfare spending, making it much more likely that the shift-worker was the benefit claimant rather than the sleeping neighbor.

Who has been impacted the most?

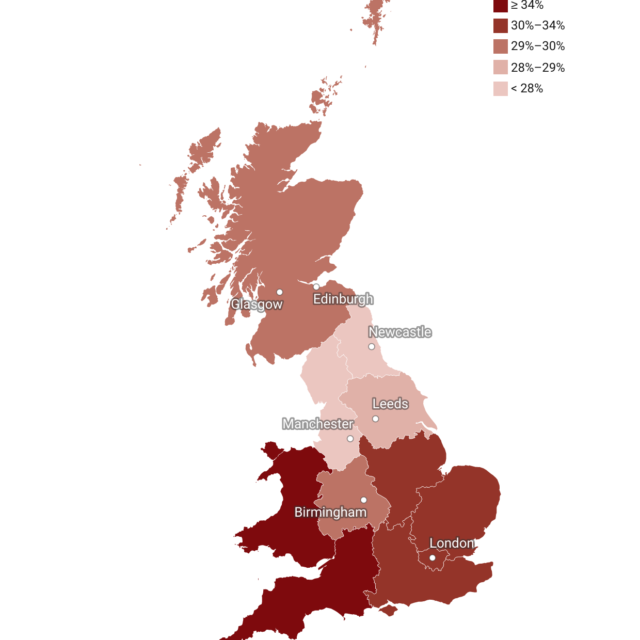

The reforms have affected the income, living standards and opportunities of a number of protected groups but the most affected of all are disabled people. They have been hit directly by reforms targeting disability benefits so that families with disabled adults and disabled children have faced the largest financial loss. Lone parents have also been adversely impacted, the majority of whom are women. Larger households and children have been affected by the decision to limit eligibility to tax credits and UC to the first two children. And the benefit cap has hit larger families particularly hard.

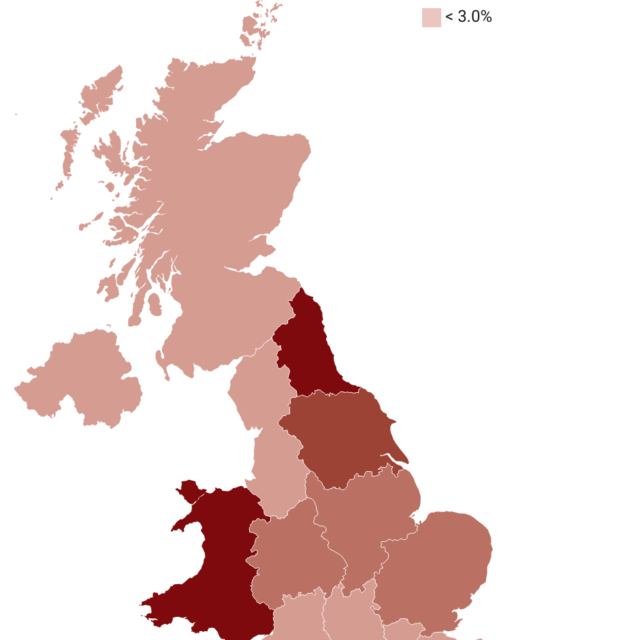

Some of the groups most affected were already the most disadvantaged. Ethnic minorities have been impacted disproportionately because of existing higher rates of poverty and in some cases because of location and family size. Some groups, in particular disabled people and women – especially as lone parents – are affected by changes to a range of benefits, as related research on the cumulative impact of the reforms by Jonathan Portes and Howard Reed, very clearly shows.

Overall, the impact of the reforms has been largely a result of their design, but implementation has been significant for some reforms, for example in use of sanctions. The assessment process for Employment and Support Allowance and for Personal Independence payments has impacted on the health and wellbeing of some applicants; and the transition from discontinued to new benefits has led to payment delays and hardship.

Re-thinking welfare

A number of the reforms are still to take full effect, including the two-child limit on child benefits and in-work conditionality within UC. The negative impact from the benefit freeze will also start to more acutely felt, as inflation rises. But rather than introduce further measures, it seems likely that the Government will focus on implementation of its existing welfare policies. This is particularly likely in view of the time and resources demanded by Brexit but also because the referendum vote highlighted some of the structural causes of inequality in poor infrastructure and low quality work. Further measures may also lack wider support: only 21 per cent of the British public thinks that most social security claimants don’t deserve help, down from more than a third in 2011 and the lowest ever recorded.

Our review provides some guidance on how the negative impacts of reforms to welfare and welfare to work might be reduced. Principally, this would involve reversing some measures which have impacted most on the living standards and welfare of protected groups. Priorities for such action should include the freeze on benefits and Personal Independence Payments (PIP). UC should revert to its original intended design, of simplifying the benefits system, aligning out of work and in-work benefits and making it easier to transition into employment. These changes to policy would be relative easy to implement but whether they would be politically straightforward is not certain.

But current circumstances also offer the opportunity to reconsider the welfare system in the light of evidence of the disproportionate impact of the reforms on some protected groups. We suggest three priority areas:

- serious consideration of how welfare and welfare to work policies can actively support equal participation of women and lone parents

- ensuring that disabled people who are able to work have the support they need

- ensuring that disabled people and their families are adequately financially supported where they are unable to work

Moreover a review of welfare policy should ensure that families in some ethnic minority groups where larger families are more usual are not penalised. A change in policy direction should also require the use of evidence to review how people might be better supported into work in ways which do not involve benefit cuts. This must involve acknowledging that structural, not just individual, barriers to work need to be addressed

More fundamentally, it requires revision of the belief system behind the reforms, away from the view that inactivity is a life-style choice and towards recognising that effective provision and support are more effective than punishment. This can only happen if we reframe welfare positively, as a means to achieve an acceptable standard of living and as something needed by all sections of society at points in their lifetime.