Take it from an Economist, Jack Monroe’s Argument is a Fair One

A study into whether Jack Monroe’s argument that the prices of low-cost food items are rising faster than the average has caused hysteria in parts of the media. Some have written articles decreeing that the study completely disproves her assertions, whereas others have claimed her point was vindicated. Max Mosley, an Economist at NIESR, thinks they’re all missing the point, and goes through what we can and cannot infer from this study, with a general plea for people who should know better to stop being so quick in their condemnation.

Post Date

Post Date

Reading Time

Reading Time

A physicist, a chemist, and an economist are stranded on an island with just a can of food. The physicist and the chemist design an ingenious mechanism for opening the can; the economist’s contribution is merely: “assume we have a can opener”.

This quite amusing phrase, originating with Kenneth Boulding in the seventies, points out the well-documented phenomenon that the assumptions economists often rely on can sometimes be too far detached from reality and from people’s lived experiences. It takes all sorts of medians to yank us back into the ‘real world’. Sometimes this takes the form of an essay from a Nobel Laureate like Robert Lucas or Paul Krugman to show economists the errors of theirs ways, but other times it takes the contribution from private agents – that’s economist speak for the wider public – to point out a flaw in how economists do their work.

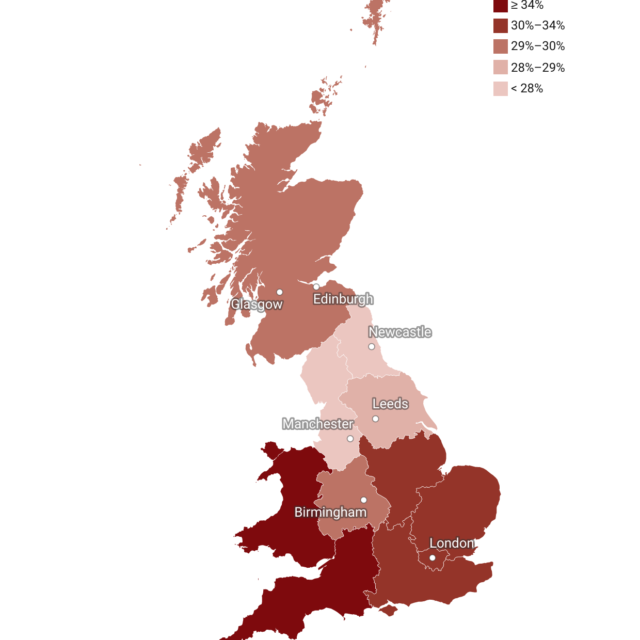

So, in January of this year, a fairly niche Twitter thread about food prices from Jack Monroe inadvertently thrust the food-writer and activist into the spotlight of an oddly fierce economic debate. She noticed that the types of food she would buy when she was a foodbank user were rising at a far faster pace than the reported inflation at the time, with some products doubling in price. Her central point was that the official inflation figure, at that time 5 per cent for food, appeared to mask the actual effect it was having for particular households.

I will spare you an explanation of how the ONS arrive at their inflation figures, but what you need to know is this figure is just an average. Inflation of 5 per cent does not mean all products are rising neatly by this number. There will be some above and some below this growth rate. What you also need to know is that the ONS does not track the change in price for every single product, which would cost a fortune and take years. Instead, they track a list of 700+ goods and services the average household is likely to buy.

What Jack was noticing was, to some, a well-known issue with using these very aggregate figures:

1) average ‘headline’ figures mask the extreme effects at both ends. If some products doubled in price, but the same amount halved we would not notice a difference, but the story on the ground has changed dramatically.

2) not all households buy the same goods; if low-income households are likely to buy more staples and ‘own-brand’/value products, then we need to know how much those products are rising by.

Both of which mean headline inflation figures are not really telling the full picture, as it could be that low-income households are experiencing even higher price rises for the products they buy. Just looking at the average will not tell you this.

This may seem to be an assertion, but it needed and uncontroversial. In fact, even the ONS – who collect official inflation figures – are already aware of this issue, but Jack’s campaign prompted them into a pilot study to see whether this difference really existed. That experimental report was released on Monday. Despite the results being a mixed bag, plenty of people have overreacted in both directions and many of them should know better.

Most commentators have somewhat missed the point, so here is an idea. Let us go through what we can and cannot conclude from the pilot study, starting with what Jack’s general point is (and why it is really not that controversial).

What is the ‘Monroe Hypothesis’, why has it been seen as controversial?

What Jack is arguing forms the fundamental principle of microeconomics. The Bank of England and other macroeconomists like to use aggregate figures, especially for inflation, as they are concerned about the impact on the broader economy. Microeconomists and now, by extension, Jack Monroe, think that when we want to know what the effect of this is on particular households, average figures do not tell us an awful lot for the reasons mentioned earlier.

The comments from some columnists and economists have, in my view, missed this point. Usually when someone tells a microeconomist to move away from an average figure and drill down towards the individual level more, they respond with glee. In fact, we talk about little else other than our dislike of ‘average’ figures.

So why some commentators got so defensive over her suggestion remains a bit of a mystery to me; perhaps they are blinded by their unease at being told how to do economics from an outsider. Maybe we are all a little out of practice with knowing what figures are helpful in this high inflation period we are in, given the last time we all faced prices rising this fast I was not even born! Either way, the fact that the experimental ONS study has started to look into this is very welcome.

What we can conclude from the ONS study

The study scraped prices of the cheapest products from online supermarkets and found that specific items like pasta rose in price by 50 per cent, far higher than the 5-10 per cent average rise in food prices. Interestingly, the price of the second cheapest product is substantially higher than the cheapest, which is potentially quite a significant driver of challenges for low-income households in navigating this cost-of-living crisis, especially if they work during the day and have to shop when there is less availability.

But on the whole, taking all these value items together, they rose at quite a similar pace to the average. Only very specific items outpaced this average rate to a noticeable degree. So, the results themselves are a mixed bag. There is enough evidence to support Jack’s central point that there is significant variability underneath average inflation figures, which likely harms low-income-households, but not enough yet to spot a convincing pattern. We have a proof-of-intuition if you will, but not a fully-fledged study that confirms proof-of-concept. The study did not include all supermarkets, as notable exceptions were Aldi and Lidl, and the ONS recognises such limitations.

What we cannot conclude from the ONS study

But the lack of concrete findings did not put off many commentators from trying to conclude that the study invalidated Jack’s point, whereas others used the pasta example to show that the prices of value products were rising more than already high inflation figures.

Both of these are wrong. To the commentators who wanted to disprove her work, I would suggest there was more evidence there to support her basic point, that there are some staples whose prices are rising way faster than the average we like to report.

But the central reason why all of these articles are wrong? It was an experimental study. There is no point in trying to elicit a narrative from a study that can only track the prices of a few products from a few supermarkets. Any attempt at doing so, in my view, just highlights a personal bias.

At the risk of repeating the old adage that ‘more research is needed’ trap, but it is certainly the case here. This work is vital for our understanding of the effect of inflation, but it is just a pilot study. So the ONS need to push this research even further, columnists need to read the research they are reporting on more, and economists need to stop assuming everyone has a can-opener.