The Calls for Expansion of Free School Meals are Timely and Warranted

As rising costs of living put pressure on families, free school meals are being discussed in the media. Our Senior Social Researcher, Ekaterina Aleynikova, in conversation with our Deputy Director Professor Adrian Pabst, argues that now is the time to make the case for specific policy intervention in this area.

Why are free school meals being discussed in the media now?

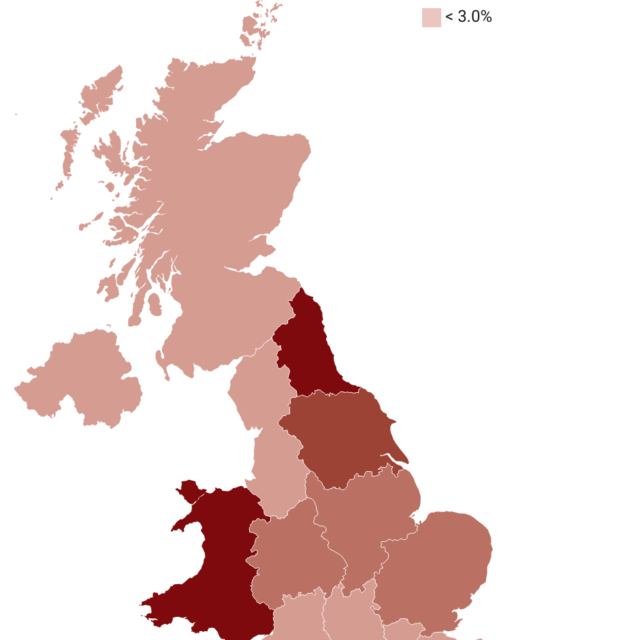

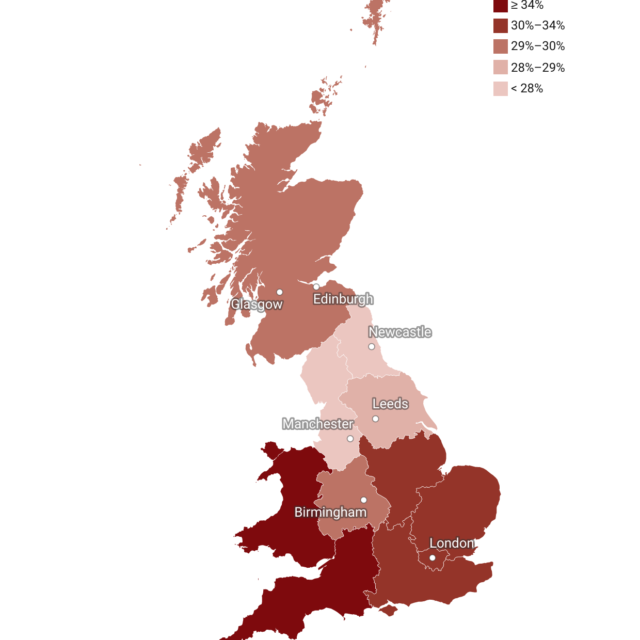

As the rising costs of living put pressure on family budgets and impact affordability of food, a number of charities have backed a campaign for free school meals to be extended to more children. Currently, there is a complex patchwork of rules according to which school children in the UK are eligible for free school meals: all children receive them up to year 2, after which there are different eligibility thresholds in each nation of the UK based on family incomes. The lowest threshold is in England, where free school meals are provided to children in Year 3 and above only if they live in households on income-related benefits and annual income of up to £7,400 after tax. The coalition of organisations led by the Food Foundation is pushing the Government to extend free school meals provision to all children living in households on Universal Credit. That would extend provision to around 800,000 children in poverty currently not receiving free school meals.

This is not the first time that school meals have been a topic for discussion in the media. They have been a notably political topic in the UK for some time and the subject of some successful media-friendly campaigns. In the 2000s, the TV chef Jamie Oliver’s ‘Feed Me Better’ campaign led to changes in the content of school meals and increased funding. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the footballer Marcus Rashford successfully campaigned for the Government to provide free school meal vouchers to eligible children during school holidays. Both of those campaigns managed to get direct interventions from the Prime Minister. As of yet, there has been no indication of Rishi Sunak being inclined to respond similarly.

What is the evidence to support free school meal expansion?

There is extensive evidence that providing school meals to vulnerable children improves both health and learning outcomes. Providing a nutritious, hot lunch results in long-lasting health outcomes through improved diet quality and by reducing obesity rates. Free school meals also help children to learn by reducing children’s absences from school due to illness, and improving concentration and attainment while they are in school. A range of studies in the UK and worldwide demonstrate positive impacts on diet quality, food security, BMI and academic performance. Universal free school meal provision has also been shown to increase take-up of free school meals by those who are already eligible, suggesting that wider provision reduces stigma or other barriers to take-up.

There is also some evidence to suggest that expansion of free school meal provision in England would present a positive return on investment. A cost-benefit analysis commissioned by Impact on Urban Health estimates that expanding the scheme to all children in households on Universal Credit would generate £1.38 in economic and social benefits for every £1 invested.

So why has it not happened yet?

As with any spending, fiscal concerns are a factor in decision making. The Department for Education currently spends £470 per year per pupil on means-tested free school meals. Expanding the scheme to 800,000 more children would thus imply around £400m further funding annually, in addition to any capital expenditure required to expand school kitchen facilities. While undoubtedly a significant outlay, that would constitute only a small fraction of what Government spends annually on welfare and education, and would offer good value-for-money. The wider social benefits of the scheme through improved educational and health outcomes would ultimately save the Government money by increasing future earnings potential and alleviating pressures on the NHS. However, such long-term benefits are not always well accounted for by the Government’s short-term decision making.

More widely, the structure of the benefits system may present a conceptual barrier to widening free school meal provision. Universal Credit aims to bring all benefits under one umbrella, with a strong focus on moving the recipient away from receiving other benefits. A benefit in kind such as school meals provision does not fit neatly in this conception of the welfare system, as it could be argued that Universal Credit should be able to cover provision of meals to children. However, this argument does not hold well in the context of the rising inflation. As price increases outpace any uplifts to Universal Credit, families are less able to afford essentials like food and heating and are faced with difficult choices. Provision of meals at school is a direct and efficient benefit, and expanding it would ensure that fewer children in poverty are having to go hungry in the cost-of-living crisis. The funding going directly to support children also has the advantage of commanding high public support. A recent YouGov poll shows that 72% of the public would support increasing free school meal provision.

Ultimately, the decision on whether or not to invest in more free school meals will come down to political priorities. It is telling that amongst the five top priorities announced by Rishi Sunak last week, none focused on addressing inequality or supporting the most vulnerable households during the cost-of-living crisis. Investing in childhood outcomes, however, would generate benefits for decades to come, and should not be overlooked.