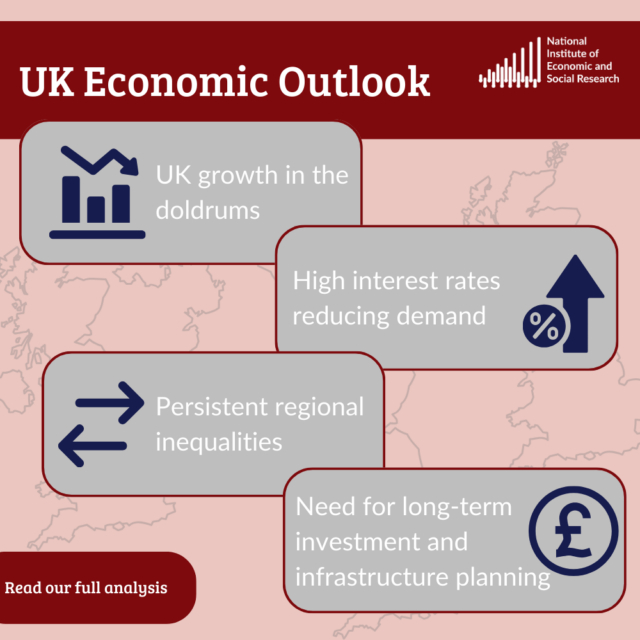

The Outlook for the UK Economy

With our most recent UK quarterly forecast identifying some systemic economic challenges around UK economic performance, and identifying some potential policy options to address them, our Deputy Director for Macroeconomic Modelling and Forecasting, Professor Stephen Millard discusses some of the key themes with our Head of External Affairs, Neil Lakeland.

The most recent NIESR UK Economic Outlook highlights how living standards have been falling, and are still falling for almost half of UK households. Which factors are contributing to this bleak picture?

The three shocks of Brexit, Covid-19 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine – which we must never forget represents a humanitarian tragedy – have all contributed to reducing the living standards of UK households, by which I mean a substantial fall in real incomes. The rise in the costs of trading with our largest trading partner – the European Union – resulting from Brexit means that UK households either pay more for imported goods, which are relatively more expensive than previously, or will switch to more expensive domestic goods. Either way, real income is reduced. Covid-19 – leaving aside the human tragedy of over 130,000 excess deaths in the United Kingdom – led to supply chain problems as different countries opened at different speeds. Again, the result was higher relative prices and lower real incomes. Finally, the Russian invasion of Ukraine resulted in a large rise in energy and food prices – the so-called ‘cost of living’ crisis – which pushed price inflation well above wage growth and, so, lowered real incomes.

To sum up, all three shocks resulted in a large ‘terms of trade’ shock for the United Kingdom where the prices of things we buy rose by more than the prices of things we produce and sell, thus making us worse off as a nation. In our Autumn UK Economic Outlook, we estimate aggregate real personal disposable income in the third quarter of this year to have been 0.7 per cent below where it was in the fourth quarter of 2019 before the Covid-19 pandemic hit. And we also project that for the 40 per cent of people in income deciles 2 – 5, real incomes will not return to pre-pandemic levels until the end of 2026.

The UK is set for very low economic growth at best for the foreseeable future. Does this mean we will continue to become worse off over the next few years?

As you say, the outlook for UK GDP growth is bleak for the foreseeable future. Although we do not expect to see a recession in the United Kingdom, we see growth of only 0.6 per cent this year and 0.5 per cent next year as the rapid tightening in monetary policy we saw between December 2021 and August of this year continues to bear down on output. However, with price inflation continuing to fall while earnings growth remains high, we expect to see real incomes rise over this period. Specifically, we expect real personal disposable income to rise by 2.8 per cent over the next two years, that is, between the third quarter of this year and the third quarter of 2025. So, on average, people in the United Kingdom will become better off over the next couple of years (and hopefully beyond). But, as I said earlier, real incomes are currently below where they were before the Covid-19 pandemic and for a large segment of the population will remain below this level for the next three years.

You anticipate that the rate of inflation is going to stay above the 2 per cent target until the end of 2025. What factors are keeping it high, and what are the implications of this?

The CPI inflation rate is currently 6.7 per cent. We expect it to have fallen to around 5.1 per cent in October – with the actual number being released later this week – as a result of the huge rise in energy prices in October 2022 dropping out of the annual comparison. But we expect inflation to stay above the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target until around the end of 2025, that is, two years from now. But that is not necessarily a bad thing. As is well known, monetary policy acts with ‘long and variable lags’. What this means is the effects of an interest rate change today will take a while – around a year – to feedthrough into demand and output and then a further length of time – around another year – to feedthrough into inflation. In a situation of very low growth – that is, where we are now – the Monetary Policy Committee will be anxious not to ‘overtighten’ monetary policy as this could lead the economy into a recession. So, although it could bring inflation back to target more quickly by raising interest rates by even more than it has done, the Committee will think that, with inflation returning to target over the roughly two years it takes monetary policy to have an effect, it has done enough.

So, what is keeping inflation high? With the large increases in energy prices dropping out of the annual comparison the main contributors to inflation are food and non-alcoholic beverages, alcohol and tobacco and services. With producer prices falling – that is, negative producer price inflation – we can expect goods inflation to continue to fall. Services producer prices, however, rose by 3.4 per cent in the year to the third quarter of this year, indicating continued pressure on services inflation. But even more telling for services inflation is the high growth rate of earnings, given that the bulk of costs in services are wages. Average weekly earnings grew by 8.1 per cent in the year to the three months between June and August of this year, although this was affected by bonus payments to NHS staff and civil servants. We expect average earnings to grow by 7.2 per cent this year and 7.1 per cent next year as workers attempt to bring their real wages back to where they were before the cost-of-living crisis. We can thus think of high wage growth as the proximate cause of above target inflation over the next year or so.

What are the implications of this? As I suggested above, provided inflation follows the path we (and the Bank) expect, then we can say that the Monetary Policy Committee has managed to steer the economy through the very tight space between allowing inflation to remain high for even longer by setting policy too loose and causing a recession by setting policy too tight. However, there is always a risk that the high wage growth we expect to see for the next year or so leads firms to continue to raise their prices by similar amounts in order to maintain their margins. And this, then, could lead to further high wage growth and so on. This is what economists call a ‘wage-price’ spiral and it is up to the Monetary Policy Committee to remain vigilant, tightening policy further if they see evidence that this risk might be transpiring.

One of NIESR’s policy recommendations is to raise public investment. Why does this matter? And assuming that investment is raised, how would that change the picture for the UK economy?

Public investment in the United Kingdom has been low for a long time – having fallen from an average of 4.5 per cent of GDP (net of depreciation) between 1949 and 1979 to an average of 1.5 per cent of GDP (net of depreciation) between 1980 and 2022 – and remains low relative to other developed (and indeed developing) economies. Public sector gross investment between the first quarter of 1980 and the second quarter of 2023 averaged 4.9 per cent of GDP in the United States, 7.5 per cent of GDP in Japan and 4.1 per cent of GDP in France while only averaging 3.1 per cent of GDP in the United Kingdom. As noted by the UK Productivity Commission, which NIESR hosts, this matters because the lack of investment in infrastructure, education and skills, and healthcare is likely to be one of the explanations for poor UK productivity growth since the global financial crisis. Furthermore, as noted by Professor Nigel Driffield in his evidence presented to the Productivity Commission, the academic literature suggests that public investment is complementary for business investment. That is, additional investment in, especially, infrastructure leads to greater business investment as it becomes more profitable to invest. In turn, this would further raise productivity in the United Kingdom.

Increasing public investment to 3 per cent of GDP every year, as we recommend, would gradually lead to a rise in the public capital stock, business investment and productivity growth with the result that GDP would be higher than otherwise. So, although the debt to GDP ratio would initially increase – unless the additional investment were financed by a rise in the tax burden – it would eventually fall as a result of the increased public investment. Unfortunately, the current fiscal rules only consider the debt to GDP ratio over the coming five years, which is not long enough for the positive effects of public investment to be realised. As a result, they create a disincentive to invest. NIESR have long argued for the need for a new fiscal framework that encourages public investment while still ensuring long-run sustainability within the public finances.