The Case for a Fairer UK Tax System

The recent turmoil in UK financial markets was in part a reaction to the announcement of unfunded tax cuts in the fiscal event of 23 September that ultimately brought down the Liz Truss government. The new Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is set to outline tax and spending when he delivers the Autumn Statement on 17 November. In a context of low growth and increasing income and asset inequality for millions of households, our Deputy Director Prof Adrian Pabst spoke with Dr Larissa Marioni, a Senior Economist in NIESR’s Public Policy team. She is the co-author of a recently published report on progressive consumption taxes.

Why a progressive consumption tax?

The UK tax system is designed to reduce disparities between the top and the bottom of the income distribution, but increasing inequalities raise the question of how create a more progressive tax system than is currently the case. Tax policy is at the centre of the UK political debate and yet there has been little discussion of consumption taxes. The main argument for a consumption tax is that, unlike an income tax, it does not penalise savings and investments.

It is worth mentioning that a direct consumption tax is a tax on individual’s total consumption across a year, which is different from an indirect tax on expenditure, including Value Added Tax (VAT), that tax at the point a purchase is made. Moving from the current income and consumption taxes, such as VAT, to a direct progressive consumption tax is crucial for decreasing inequality and making sure that the tax system is fair.

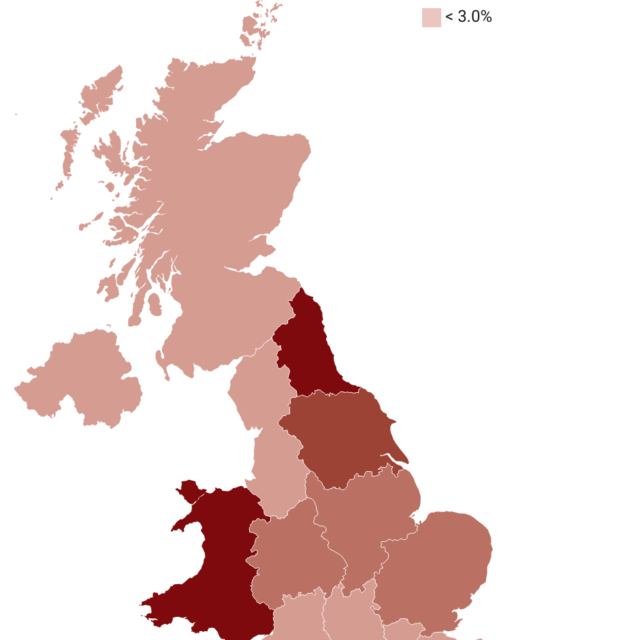

At present, lower-income households pay more indirect taxes than higher-income households as a proportion of their disposable income because of high marginal tax rates combined with the nature of VAT. A possible way to solve this issue is making sure that progressivity is in place in terms of a direct consumption, or expenditure, tax.

How could a progressive consumption tax be implemented and what are some of the transition issues?

In our report, we undertake a comprehensive review of how a progressive consumption tax could be implemented. For instance, the 1978 Meade Report suggests a universal expenditure tax (UET), in which all purchases of assets should be deducted from the tax base, and all sales of assets and income yield on these assets should be added to the tax base. Alternatively, a two-tier expenditure tax (TTET) uses a combination of two separate taxes, one for the lower tier of taxpayers’ expenditure, an income tax with 100% capital allowances, and a surcharge on levels of expenditure above the basic rate.

Regardless of the implementation method, a progressive, direct consumption tax raises some transition issues, such as how to deal with cross-border movements of goods and services, how to avoid double taxation for pensions and how to tackle capital taxation. One way to handle these issues is to implement a progressive, direct consumption tax gradually and allow for exemptions, such as tax-free thresholds.

What are the distributional consequences of introducing a consumption tax?

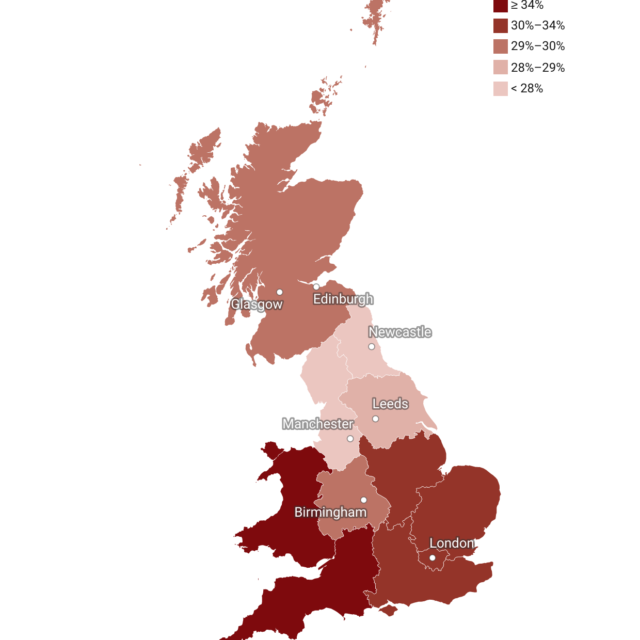

To investigate the impact of introducing a consumption tax, our research compares a base simulation, which is designed to represent the current tax system and is representative of the UK, with three alternative policy counterfactuals, in which taxes are set to obtain budget neutrality with the base scenario in a 30-year horizon. First, we replace VAT and consumption duties with a direct flat-rate tax on consumption of 15%. In this case, results highlight that the consumption tax has limited distributional effects.

Second, we replace VAT, consumption duties, direct income taxes and national insurance contributions, with a flat-rate direct consumption tax rate of 41.3%. In this scenario, we find that a direct consumption tax is disproportionally favourable to the richer households, with consumption decreasing by around 10% for the bottom quintile of the income distribution and increasing by around 20% for the top quintile.

Finally, we replace indirect consumption and direct income taxes with a progressive, direct consumption tax, which consists of a flat-rate direct consumption tax rate of 78% with a tax-free threshold of £100 per week. We find that a direct progressive consumption tax enhances lifetime consumption and smooth the trend over the lifecycle. It also allows for flexibility of work, as we see a decrease in the average hours worked before the age of 25 and from the age of 55, but an increase in average hours worked during prime working years. Additionally, a direct progressive consumption tax encourages savings and increases wealth accumulation for all parts of the income distribution.