The Chancellor’s 2022 Autumn Statement Choices

As we await the coming Autumn Statement from Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, our Deputy Director for Macroeconomics, Stephen Millard, spoke with Kemar Whyte, a Principal Economist on the team, about his views on the recent fiscal turmoil and what we might expect to hear on Thursday

What went wrong with fiscal policy over the summer?

Only everything.

In the last 4½ months, the UK has had four different Chancellors of the Exchequer – namely, Rishi Sunak, Nadhim Zahawi, Kwasi Kwarteng and now Jeremy Hunt. Unprecedented in recent British History. With the UK economy facing high inflation and a potential recession, Chancellor Kwarteng held a ‘mini-budget’ on 23 September, during which he announced several tax cuts, together with a significant support package for households – the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) scheme – and firms to help them cope with rising energy bills. Unfortunately, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) were asked not to provide their independent analysis of the effects of the announcements in the mini-budget on the government’s ability to meet its fiscal targets and on the state of the economy more generally. An important underpinning of the credibility of the fiscal framework is precisely the independent oversight that a body such as the OBR can offer. Given the absence of an accompanying OBR analysis of this major fiscal event, and the ‘unfunded’ nature of the tax cuts, both sterling and bond prices fell significantly. The associated rise in gilt yields reflected both a fundamental response of interest rates to an increase in government borrowing and an additional increase in risk premia resulting from the uncertainty created by this event. The fall in bond prices was large enough that, a few days later, the Bank of England was forced to intervene in the gilt market to prevent gilt fire sales leading to a crisis for pension funds.

All the talk is of spending cuts and tax increases in the Autumn Statement, but do you think that now is the time to be doing that?

The new Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, reversed most of the policies in the mini-budget in his announcement on 17 October, reducing fiscal risks substantially, but not entirely. We will see how much further the Chancellor decides to go with spending cuts and/or tax increases in the Autumn Statement on 17 November, though it is not clear that further spending cuts or tax increases would be wise at this time.

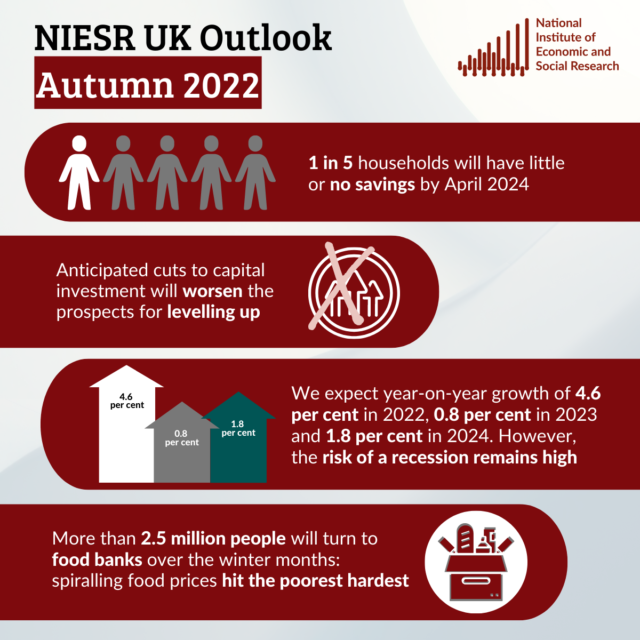

It is not clear that the Chancellor should make sweeping spending cuts or tax increases. The economy is still facing a terms of trade shock resulting from the war in Ukraine, and this is leading to real hardship for particular segments of the population. In such times it makes sense for the government to increase borrowing to support the most vulnerable households, to clearly communicate this to the public, and to put in place a plan for reducing public-sector debt at a point in the future once the shock has dissipated.

Furthermore, our latest forecast suggests the government might not even need to find any more savings in order to hit its own fiscal targets. The increases in corporation tax, together with ‘fiscal drag’ resulting from the combination of higher inflation and frozen tax thresholds, mean that the budget deficit will start to fall in 2023-24. As we have argued in this Box in our most recent Outlook, high inflation can benefit the public finances by devaluing public-sector debt.

So, assuming the Chancellor ignores us, where do you think he might look to cut spending and increase taxes?

The Chancellor has warned that he will need to make difficult choices to restore fiscal credibility, but I would err on the side of caution, particularly when it comes to spending cuts. If, as seems likely, the Chancellor plans to fill some of the ‘fiscal hole’ through cuts to departmental spending, he must understand that there are no easy savings. A recent study by the Institute for Government suggests that if the government wanted to find £40bn of cuts from departmental budgets by fy2026/27, it would require those budgets to fall by almost 8 per cent in real terms (c.2 per cent per year) over the next four years. And given government commitments to spend more on defence and the consistent protection of the health budget from cuts, this implies even larger cuts to other unprotected areas of spending.

Both the Chancellor and the Prime Minister have agreed that everyone would have to pay more tax. But there are also other likely options. For instance, there’s every chance the government will look to reduce public spending after the existing spending plans come to an end in 2024-25; lower foreign aid; and cut capital expenditure. On the tax side, we could see an energy windfall tax and an extension of the freeze of income tax thresholds.

It is thought the Chancellor needs to put in place tax rises and spending cuts worth around £55bn a year, as he seeks to lower borrowing and cut the debt burden. But economic growth will take a hit and therefore by extension, tax revenues. This reinforces my earlier point about timing and how some of the budgetary measures may not ultimately sustainably fill the fiscal hole.

Much of the problem with the government’s finances comes from the Energy Price Guarantee; is there a better way of supporting, in particular, poorer households with their energy bills?

The moment the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) was announced it was clear that this huge policy intervention was not sustainable in the long-term. The associated costs could easily reach over £100 billion in a year. However, much has changed since the announcement of this scheme, not least the announcement that the EPG is now set to be reviewed from April 2023 onwards. The extent to which the policy change will reduce the cost of the previously estimated £100-£200 billion expenditure will depend on the cost of whatever new scheme is implemented in 6 months’ time.

At NIESR, we have made an argument for what we think that scheme should look like. We have proposed, for some time now, a variable price cap which would provide targeted support for households in a more cost cost-efficient way for the government, that would improve public finances. Specifically, we have suggested transforming the single point energy price cap into a variable price cap where the price per unit of energy used rises with usage. This would mean that marginal user costs increase – therefore reducing energy bills for lower-income households while higher earners, who consume more energy, bear an appropriate share of the higher costs. This approach would not only raise the bills for those who can afford it and lower it for those who cannot, but also encourage an overall lower usage across the spectrum.