What is a Recession?

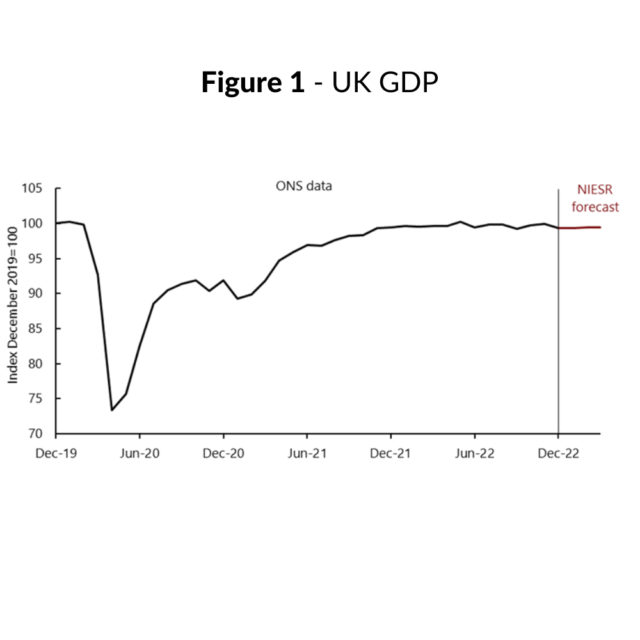

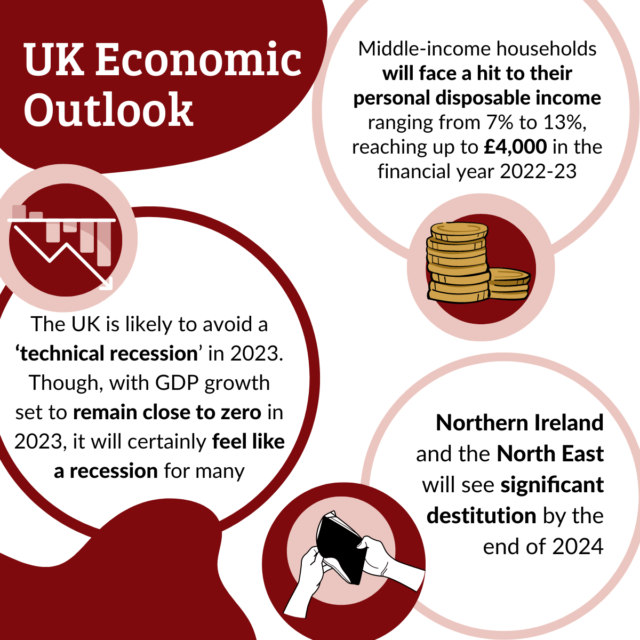

December’s GDP figures confirmed that the UK avoided a recession in 2022 and, according to the latest UK Economic Outlook, it is also likely to avoid a protracted recession in 2023. But what defines a recession? And, given the ongoing cost-of-living crisis that is affecting households throughout the UK, is it an important concept or should we be thinking about the economy in a different way? Professor Stephen Millard discusses these questions with Professor Jagjit Chadha, Director of NIESR.

Most commentators think of a recession as ‘two quarters of negative growth’. What does this actually mean and why might it not be such a good definition?

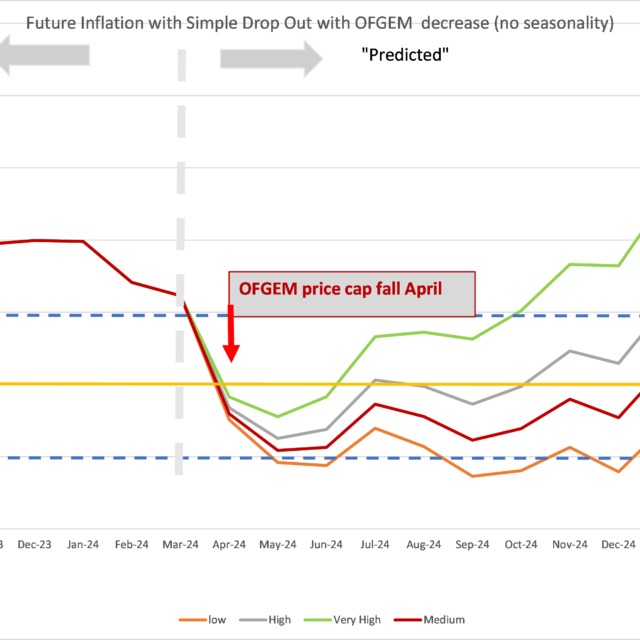

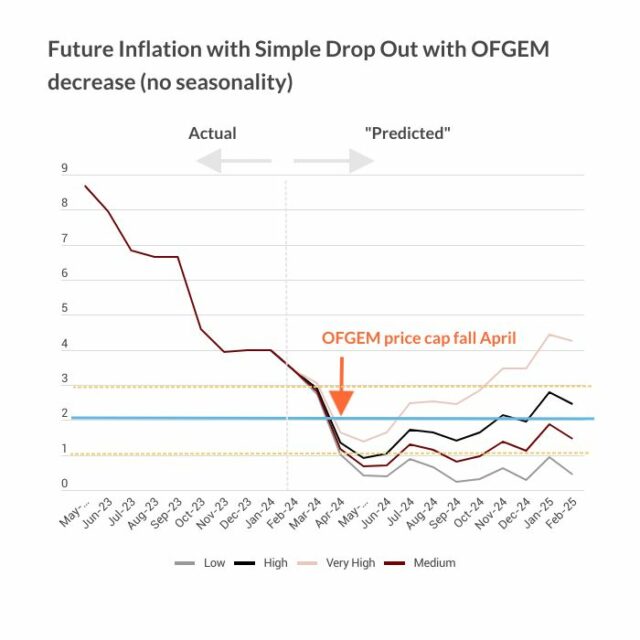

The economy, which is thought of as a machine that produces a given flow of goods and services over a measured time period, normally increases its production over time. It is this increase in production that we point to as growth and certainly in the post-industrial period we have become accustomed to annual increments in our production, as well as an escalation in income levels associated with that production. From time to time, in response to shocks, that growth in production may go into reverse and we are faced with a contraction in activity and this is typically called a recession. The question then is over what period should we measure any such decline and how large should it be to count as a recession or recession-like behaviour. Whilst much market commentary focusses on a definition based on two consecutive quarters of contraction in output, this high frequency measure can be very misleading as seasonality, data revisions and one-off shocks to a single sector may mask the true underlying path of activity. What we have in mind when we think of a recession is a sustained fall in activity across most or all sectors of the economy such that there has been a material fall in production or income.

How many ways can we think about a recession?

It is therefore more useful to focus on longer run measures such as year on year growth or whether the level of GDP is materially, for example at least some 2% of initial GDP, below its previous peak. The data released by the ONS on Friday 10 February painted a complex picture. First it suggested that the economy did not have two quarters of successive declines in GDP. Secondly that our recovery in 2022 was the strongest in the G7 in GDP terms. But it also suggested that the UK was the only G7 country not to have regained its pre-Covid peak from 2020 Q1, as we are still some 1% below that. We can go even further and note that the long run growth performance of the UK has fallen after the global financial crisis from 2.5-3% down to 1.4-1.9%, which we might term a growth recession. Ultimately a recession is short hand for a shock or set of shocks that are acting to supress growth relative to our expectations and they may act separately on demand, and be temporary e.g. monetary policy, on supply, and be permanent, from productivity or interact with each other and lead to a slump. The word recession does not replace the need to think carefully about what is going on.

Should we bring distributional issues into our thinking on this and how might we go about doing that?

The aggregate measure of GDP growth masks many disparities and differences. Particular segments of the household income distribution and the increase in regional economic inequality, which itself is closely related to sectoral performance, may each portray recession-like behaviour and that may be masked by focussing on a top line aggregate. Understanding where in the distribution shocks and problems are emerging may help early diagnosis and policy interventions. It could also be that a more granular picture may provide more robust measures on the state of the economy that can be used to corroborate aggregate indicators. Understanding the evolution of a modern economy of some 67mn people requires more than a sequence of a single “noisy” monthly estimate of activity. We need to capture the distribution, explain it and think of the impact of appropriate policies.

For further reading on this, please see this blog on the Economics Observatory or this ESCoE Discussion paper.