Evaluating the 2022 Autumn Statement

In the wake of the Chancellor’s 2022 Autumn Statement, NIESR Deputy Director Professor Adrian Pabst spoke with Economist Max Mosley from the Public Policy Team about both the positives and negatives of this fiscal event, as well as what should happen next.

What was good about the 2022 Autumn Statement?

This was like many of the previous fiscal interventions, one step forward and one step back. Given the doom and gloom of the previous year, it is important to recognise what was good about the 2022 Autumn Statement. Raising benefits and pensions in line with September’s inflation rate of 10.1 per cent is the right thing to do. It will cushion the blow from the triple shock of soaring energy, food and housing costs for many millions of households.

The approach to energy prices, which we have long criticised for being a wasteful subsidy that disproportionately benefits the high-income households who use the most energy, has been made less universally generous and more targeted through enhanced payments to those on Universal Credit. This is a step in the right direction.

Lastly, leaving aside questions about how credible it is to schedule tax rises and spending cuts after the election, the principle of postponing fiscal consolidation during a period of much slower growth is sensible. It will help shorten the likely recession while giving households and firms more time to adapt to future conditions. And if economic conditions were to improve, there is the option not to go ahead with all of the tax increases and cuts to public expenditure.

Where was it lacking?

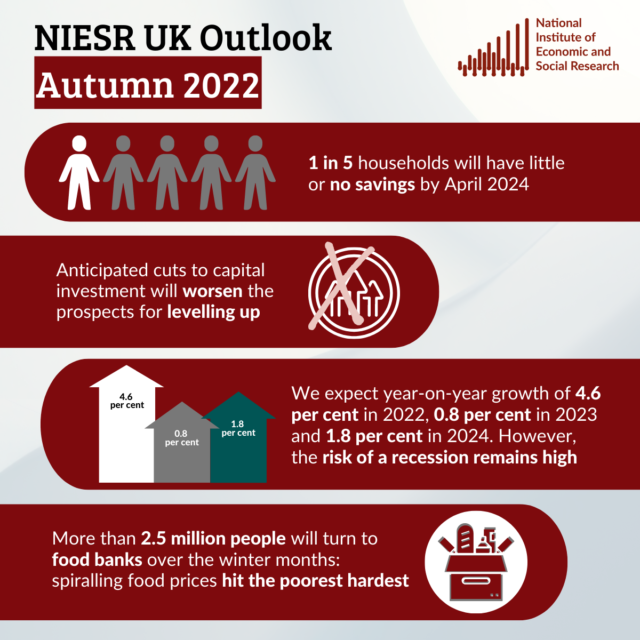

But this is where the good news ends. The energy plan is still a universal subsidy, just slightly less so, at approximately £3,000 per year for a typical household rather than the current level of £2,500. So, after April 2023, there will be a lack of incentive to save energy, besides a disproportionate benefit to wealthy households and a significant fiscal commitment (the six months to end of March 2023 are estimated by HMT to cost about £50bn). What is problematic is that the government are combining a less generous general subsidy for all with more narrowly targeted assistance: this will help the poorest but lower-income households not on welfare will actually see their energy bills go up further.

It is this group of households that our work at NIESR has focused on. They will be hit not only by higher energy and food prices but also be dragged into higher income tax bands as a result of the government’s decision to freezing income tax thresholds until 2028 and increases in Council Tax. This applies to a lot of people, which is why the OBR estimates that on average the country will still see a 7 per cent reduction in living standards. Those low-income workers are now likely the hardest hit people in the country and the lack of precision in the energy plan has meant they will struggle more than under alternative policies.

What could and should the Chancellor have done?

The main issue here is the energy plan. Making a universal subsidy less generous to make it more targeted has tied the hands of the Treasury, as it means they can only help those they know about (i.e those 5 million or so on welfare). We need an approach that can lower the bills for those who are not on welfare.

At NIESR we have advocated a Variable Price Cap, which raises the unit cost of energy with its usage. This would lower the bills for lowest income households, while raising it for the richest potentially by the same amount. This not only has the comparative advantage of helping not just the very poorest in society but also those on low incomes too, while incentivising lower energy demand, which has ecological (and national security) benefits and is fiscally more cost-effective.