Fixing forecasting at the Bank of England

Let’s face it, the Bank of England’s forecasting performance over the past two years has not been good. For example, in August 2021, the forecast for inflation in the fourth quarter of 2022 was 2.5%; the outturn was 10.7%.

Of course, no-one in August 2021 could have predicted the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the effect it would have on inflation in 2022 and 2023. But it could be argued that the bank continuing to underpredict inflation in 2022, and underweighting the risks of higher inflation more generally, led to looser monetary policy than was warranted, generating a higher peak in inflation than would otherwise have been the case.

In May 2023, the bank’s court of directors commissioned a review into its forecasting platform. In July of that year, the bank announced that former Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke would lead such a review; he is due to report back on April 12.

This review will, I’m sure, take the opportunity to rethink not only how the bank goes about forecasting but why – that is, what it is seeking to achieve in its published forecasts.

Currently, the forecast serves three purposes. First, it provides the public with a forecast for GDP and inflation over the next three years and a sense of the uncertainty surrounding this. Second, the monetary policy committee (MPC) uses it to signal to financial markets what it expects interest rates to be at various points in the future. And third, the forecast enables the MPC to communicate what it sees as the main risks to the central forecast and how it will respond should any of these risks transpire. Given these three separate purposes of the MPC’s forecast – note that it is not the bank’s forecast – is it any wonder that one forecast is unable to deliver what is needed?

What seems to be required are three separate things.

To start, I would argue that we need to divorce the forecast from the policy decision by allowing bank staff to produce and own the forecast, including the ‘fans’ illustrating the uncertainty around the forecast. That is, it becomes the Bank of England’s forecast and not that of its MPC. Other central banks, including the Federal Reserve, which Bernanke chaired, and the European Central Bank have always done this.

Given that bank staff are producing the forecast, this would then free up the members of the MPC to concentrate on explaining their policy decisions and being clear on where they disagree. In particular, they could each indicate exactly their expected path for interest rates, conditional on there being no new shocks to the economy, and where they expect interest rates to settle. This would help with their communication with the financial markets, while also making clear where individual differences of opinion lay and came from, thus helping to make them individually accountable. Again, this already happens at the Federal Reserve with the ‘dot plots’, on which Bernanke is known to be keen.

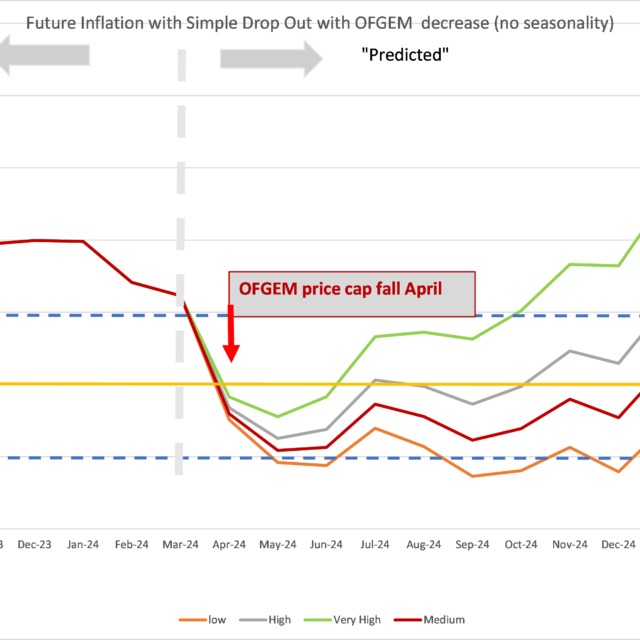

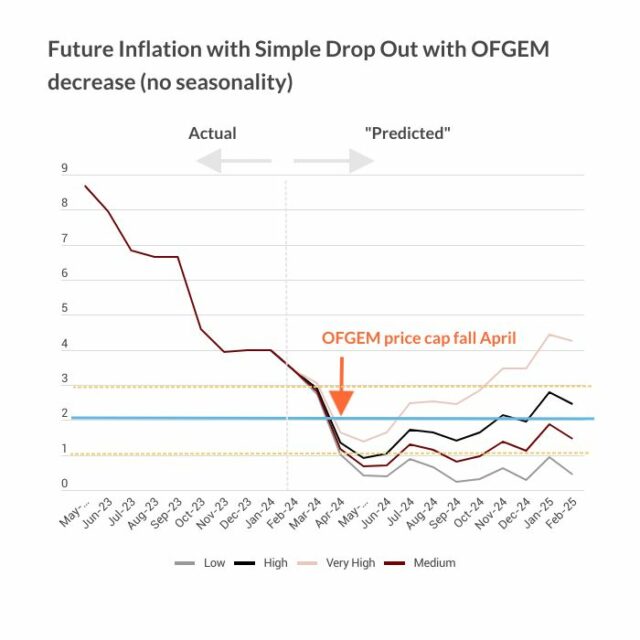

Finally, it is clear to me that MPC communication could be greatly improved through scenario analysis. Given the bank’s central forecast, the MPC could examine the effects of one or two different shocks – based on what its members saw as the one or two big risks to the forecast – on GDP growth, inflation and, importantly, interest rates, as this would provide insight into how the MPC is likely to respond to different shocks: the so-called ‘monetary policy reaction function’. I would certainly expect the Bernanke Review to recommend more use of scenario analysis in future monetary policy reports. The precise form that this takes, and how quickly it happens, will of course depend on how the bank responds.