The Key Steps to Ensuring Normal Service is Quickly Resumed in the Economy

Last week the International Monetary Fund published an update to its autumn forecast that not only suggested world growth would continue to stay in the doldrums but also that Britain would be at the bottom of the pack and in a recession over the course of 2023. On the same day, the Office for Budget Responsibility published its annual assessment of its own forecast performance. The key takeaway for many was that its forecasts had been too optimistic both on growth and on the path of public debt. The common theme to both messages is that the UK is underperforming relative to its historical experience and in comparison with its main trading partners. On that, at least, we can agree.

The day of those reports was also the third anniversary of Britain formally leaving the European Union on 31 January 2020. And over the period since the referendum of 2016 the productive capacity of the economy seems to have been impaired. We can see this best in the fall in business investment relative to trend and the slump in the rate of labour participation, with there now being as many vacancies as there are people unemployed. It is also clear that trade has been impaired, particularly for imports of capital and intermediate goods, and that may have contributed to a further to the lack of both capital and labour available for firms.

With the Bank rate now up to 4 per cent from 0.1 per cent a little over a year ago and inflation still awkwardly near to double digits, there is not a lot of joy around. The disaster of the mini-budget last autumn injected further uncertainty, with the resulting political churn causing much consternation, and led to a disconnect between bond prices and mortgage availability, which still persists to some extent and has amplified the downward momentum in the economy. As a result, measures of confidence seem to be falling to a low ebb and house prices, that great barometer of British life, have started to fall.

So what next for monetary and fiscal policy? First, our analysis of the present inflationary spiral, while predominantly the result of sharp increases in energy and food prices, cannot not entirely absolve the Bank of England from some fault. While the loose monetary policies adopted after the financial crisis may have prevented a deeper and longer depression, the absence of a clear exit strategy when coupled with the response to Covid meant the kindling had been laid for an increase in costs to be fired up rapidly to a generalised inflation.

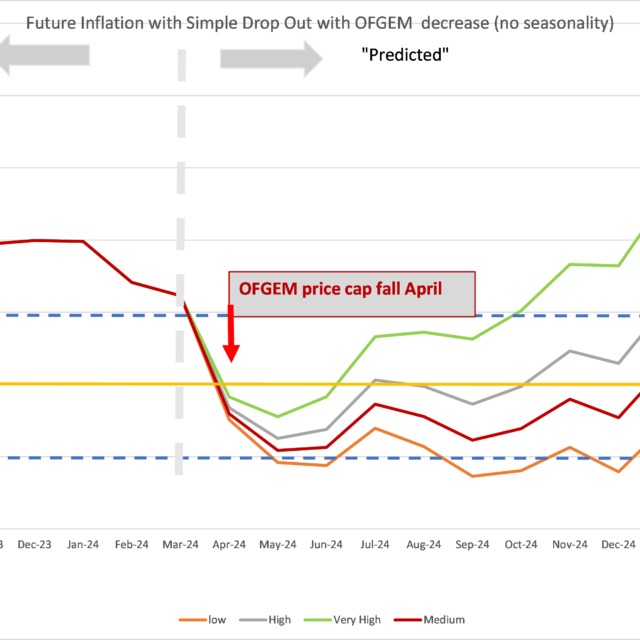

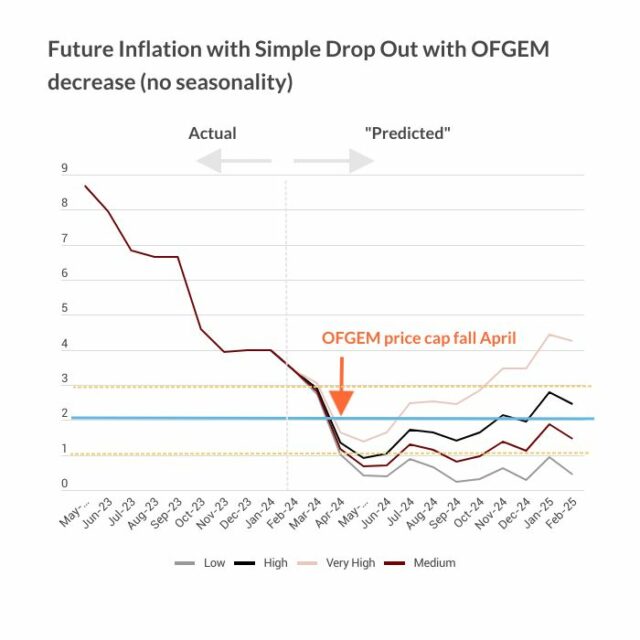

In that sense, the Bank was slow to respond in 2021 to the gradually receding Covid cloud. I am worried that the Bank, having recognised this error, may feel a responsibility to act too aggressively to the jump into energy and food prices, which ultimately is a temporary inflation. The key here is to fix on a level policy rate that will bring inflation back to target over a horizon of 18 months or so without inducing a protracted recession. If we can then keep that rate at about 3 per cent to 4 per cent, we would have done well to engineer some form of normalisation at last

On fiscal policy, it is welcome that we have an earlier timetable for the budget, five weeks away, and that it is established that the OBR should be allowed to report on any of the chancellor’s fiscal plans publicly. Expert economic institutions allow us to trust the judgments made on our behalf by politicians or, preferably, to hand over the analysis to more capable hands.

The chancellor’s speech on 27 January on his vision for the technology future was compelling, but it lacked a specific plan for bringing about structural change and any way of measuring progress against these objectives. When we miss our debt or inflation targets, we know. Who will know when we are or are not meeting our targets for enterprise, education, employment and everywhere else? And if we are not, what specifically are we going to do? Without a plan against which to monitor progress, one that is seen to tie the hands of successive politicians, the focus of getting elected will lead to an absence of long-term improvements in our economic prospects.