An Overview of the UK Economic Situation

With NIESR about to publish its Spring UK Economic Outlook on the same morning that the Bank of England publishes its Monetary Policy Report, our Deputy Director for Macroeconomics, Stephen Millard, gets the thoughts of Senior Economist, Max Mosley, on the state of the UK economy, the Outlook and the MPC decision.

With NIESR about to publish our UK Economic Outlook, could you summarise for me the current state of the UK economy?

As the economy stabilises from successive economic shocks, we are left with a sluggish economy with an increasingly limited ability to manoeuvre. To understand the state of the UK economy today and where it might go tomorrow, we need to focus 1) when will the economy recover from the inflationary shocks of the past few years and 2) will the legacy of those shocks impact our ability to grow into the future.

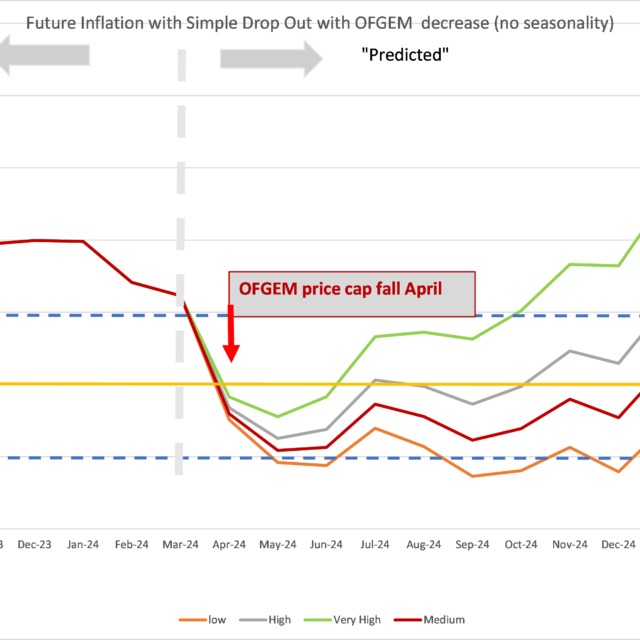

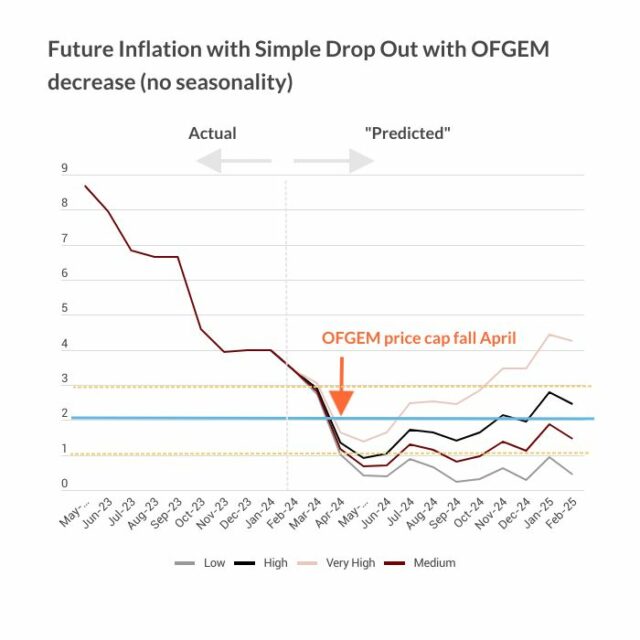

To understand the first question, it’s helpful to compare how the UK experienced this shock relative to other similar countries. While the causes of inflation have been global in nature, the UK’s peak of 11 per cent CPI inflation was one of the highest in the OECD. In March, CPI inflation was 3.8 per cent and we project this level to likely fall below the 2 per cent target in April as the energy price cap falls and the large increase in energy prices in April 2023 drops out of the annual inflation rate calculation. Overall, the inflationary shock the UK economy has been experiencing for the past few years is nearly over. The speed by which this shock will unwind will depend on how persistent the core drivers of inflation prove to be. This will partly depend on future wage growth, which has been stronger than anticipated and is currently outpacing inflation. In short, we expect this shock to be over soon, but the risks to this remain on the upside.

To understand the second question, we can first look at the prospects for future economic growth. We project 0.8 per cent growth this year, which is a welcome turn from the slight fall in GDP the economy experienced in the last half of 2023, but which remains low by historical standards. We expect this anaemic growth to be a core feature of the next few years. With the continuing war in Ukraine and conflict in the Middle East, the risks to our growth forecast are on the downside.

What are current conditions in the labour market?

The labour market continues to loosen as vacancies are filled but remains tight by historical standards.

Overall the ratio of vacancies to job seekers has fallen from its peak but remains above its pre-pandemic levels. Given the pace of the fall in vacancies we can expect this to continue falling in the near term, meaning firms will be competing less for workers, providing less upward pressure on wage growth.

Our latest analysis provides a broader look at the topic of labour market tightness, estimating this at the sectoral and regional level. In the former, we find that nearly all sectors have seen some fall in tightness, but construction is one of the only sectors that bucks this trend and is experiencing tighter conditions this year than last year. Our analysis provides a new measure of this ratio at the regional level. While we find that vacancies are the highest in London and the South-East, when compared to the high number of available job seekers in those areas we see that labour market tightness broadly resembles the national average. We estimate that Scotland, the North West and the West Midlands are experiencing notably higher levels of labour market tightness than the UK average.

Economic inactivity has become a much-commented feature of the post-pandemic UK labour-market. Since the pandemic, economic inactivity has risen by 1 million. Whereas a key driver of this rise initially was growth in the number of students immediately after the pandemic (as people took advantage of the lockdown to (re)enter higher education), today the predominant factor driving higher inactivity levels is growth in the number of long-term sick people. We provide some analysis in our Outlook that evaluates whether this could be associated with the historically high NHS waiting lists, providing some evidence to support such a correlation. However, we are keen to note that overall participation levels remain high in the UK when compared to other countries.

The MPC is meeting on Thursday and will be publishing the Monetary Policy Report. What are you expecting them to say in terms of both the interest rate decision and the wider background to that decision?

We have taken a more cautious view for when the MPC might start cutting rates in this Outlook than previously. Three months ago, we were expecting to see rate cuts in May or June given inflation was falling at a decent and consistent rate while base effects meant that large drivers of CPI inflation are due to drop out of the overall calculation in April.

However, we are now more cautious due to more sustained wage growth and emerging geopolitical risks.

Wage growth has remained elevated. We reported in our April Wage Tracker that the annual growth rate of average weekly earnings was 5.6 per cent (including bonuses) in the three months to February 2024 and total real pay increased over the year by 1.6 per cent, the highest rate since October 2021. We forecast the growth rate to be 5.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2024. This may prove to be even more persistent than we forecast given the consecutive large increases in the NMW. We heard at our latest Business Conditions Forum that firms may be less able to absorb this rise in the NMW than they were last year, given the last increase eroded differentials in wage bands which compresses the distribution of earnings within businesses. Firms may elect to raise the wages of more workers to protect differences between different pay bands, which would mean a greater overall impact on wage growth than before.

Secondly, Houthi attacks in the Red Sea and the conflict in Gaza have had some concerning similarities to the global supply chain disruptions seen in 2021 that started the inflationary shock. Shipping costs between China and Europe had increased due to recent events in the Middle East at a similar rate to how they increased in 2021. Thankfully, these costs have fallen back again but remain at a higher level than they were before the conflict.

These two factors together will mean the MPC will likely take a more cautious view for when to start cutting interest rates. If the conflicts in the Middle East escalate and/or if an impact on domestic prices materialises after they begin cutting rates it would mean that they would have to then raise them again which would be concerning for the Bank’s credibility and put monetary policy on the backfoot. Therefore, we can expect the MPC to reflect the more cautious view in the markets and within our own NIESR forecasters!

Finally, this will be the first Monetary Policy Report after the Bernanke Review. Do you have any thoughts on the Review and how the Bank might reflect its recommendations in future Monetary Policy Reports?

The review, published this month, found significant deficiencies in the Bank of England’s forecasting system, specifically noting that the software and models supporting the forecast have been neglected and that the main model either needs replacement or a comprehensive overhaul. Additionally, the report suggested abandoning fan charts for indicating forecast path probabilities, as they are poorly understood by the public and offer limited insight into risks for MPC members.

It proposed increased use of scenario analysis, which would enable MPC members to illustrate more effectively their monetary policy reaction function and communicate potential economic risks more clearly, ultimately leading to improved forward guidance and a better understanding of risks to price stability.

The review did not however question whether having the central forecasting process the responsibility of the MPC is the right approach. In many cases, such as in the European Central Bank, central bank forecasts are the responsibility of its staff rather than the policy makers themselves. Having the forecast be the responsibility of the MPC acts as a constraint on the ability of individual members to disagree with elements of the forecast and arrive at their own view; instead, the MPC are left needing always to defend the forecast.

Enabling Bank staff to own the forecasting process would then enable the MPC to focus on the scenario analysis the review recommends. These scenarios can be particularly effective in communicating what individual members see as the key drivers of monetary policy decisions and what the risks are that would cause them to change course.