Global Growth Stumbles – A New ‘New Normal’?

The pace of global economic growth slowed last year to 3.1 per cent, the slowest (except for 2019 and the Covid-hit 2020) since 2009. While part of the slowing in growth was expected due to the ending of the growth catch-up from Covid-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the resultant conflict, had a direct effect by raising energy and food prices and increasing geo-political uncertainty

Sign in to Access Pub. Date

Pub. Date

Pub. Type

Pub. Type

Main points

- In the autumn we revised down our forecast for global GDP growth in 2023 to 2.5 per cent. We have edged that down again slightly to 2.3 per cent, further intensifying the period of sub-par growth. Indeed, we forecast that recessions or, at least, recessionary economic conditions will occur in some countries. The further slowing in the pace of output growth this year comes from high inflation biting into purchasing power and the effects of the rapid monetary tightening last year, especially in the United States, Canada and the Euro Area.

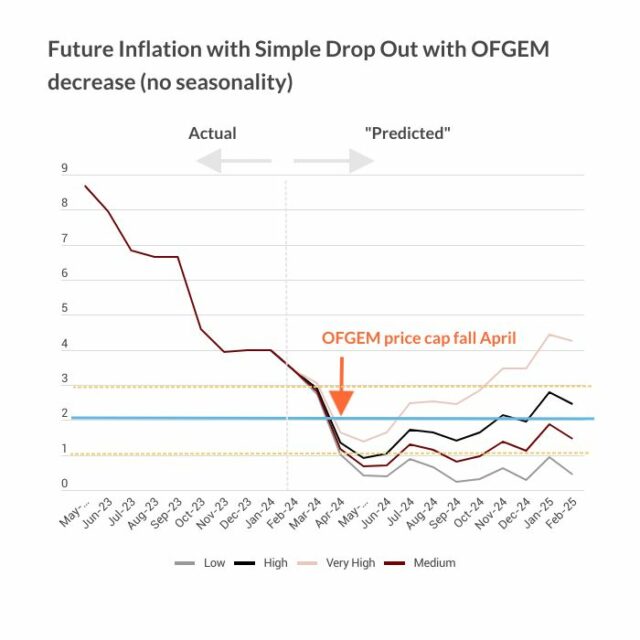

- We now think that global (OECD) inflation for 2022 was 11.1 per cent to as opposed to the 10.6 per cent we forecast in our Autumn Global Economic Outlook and we have increased our forecast for 2023 from 7.3 per cent to 8.5 per cent. Inflation has continued to over-shoot our expectations and is expected to remain high in advanced economies in 2023 because price pressures have broadened beyond volatile items such as energy and food. But lower energy prices and the effects of tighter monetary policies will feed through to lower inflation. We expect inflation to fall further in 2024 (to 5.8 per cent).

- As discussed in Box B, we think that headline inflation has now likely passed its peak in several advanced economies, though there are risks to this view from the possible intensification of Russia’s war in Ukraine and further increases in energy prices. Worryingly, ‘core’ inflation has risen and may not have reached its peak, suggesting that headline inflation could remain stubbornly above target for longer than our central case.

- With inflation expected to fall this year, the key issue for central banks will be at what point to halt policy interest rate increases. Over the past year the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) has raised policy interest rates by 4.25 percentage points and the European Central Bank (ECB) by 2.50 percentage points, tightening monetary policy in response to the inflationary impulse. We now assume, in line with financial markets, that the Fed will increase policy interest rates by a further 0.75 percentage points and the ECB by 1.50 percentage points during 2023. But, given that the pace of tightening we have already seen is contributing to the slowdown in the pace of economic growth and inflation, it is possible that interest rates may peak at a lower level.

- Given the uncertainties about the direction and duration of the war in Ukraine, energy and food prices, and the domestic responses to higher inflation across many countries, monetary policymakers should look for a sustained fall in inflation before they consider reducing rates. Our market-based assumptions show advanced-economy central banks starting to reduce rates in early 2024, reflecting the stubbornness in underlying inflation. But there is a risk that policymakers, worried about the perception of their being too slow to loosen policy, just as they were seen as having been too slow to tighten in 2021, will be tempted to reduce rates earlier this year, which we feel would be a mistake.

- Given the uncertainties over the war in Ukraine, energy and food prices, and households’ and firms’ behavioural reactions to higher prices, our forecast remains subject to considerable uncertainty. Our forecast and revisions since our Autumn Global Economic Outlook are summarised in table 1.

The pace of global economic growth is expected to slow even more in 2023, with this forecast anticipating global GDP growth of just 2.3 per cent.

This growth rate, well below the 2000-20 average of 3.8 per cent, which we revised down from our previous forecast of 2.5 per cent, will further intensify the period of sub-par growth which saw 2022 (with growth of 3.1 per cent) experience the slowest rate since 2009 (excluding 2019 and Covid-hit 2020). Because of this, we forecast that recessions or, at least, recessionary economic conditions will occur in some countries, notably Germany, Sweden and Russia.